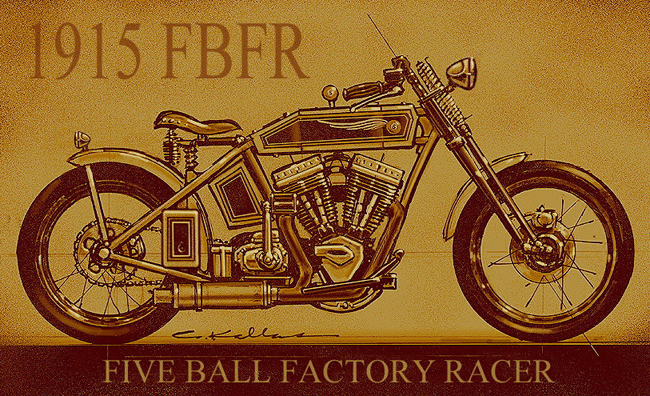

5-Ball Factory Racer, Part 9 Final Assembly

By Robin Technologies |

Every custom motorcycle build is an adventure. It takes me from one crazed time in my wild life to another. Fortunately, I'm not spilling my guts about another woman I lost during a knuckle-busting build. But this build did represent turning points. I'm about to step off into my 62nd year and sign up for Social Security. It also represented our stinky economy, and for the first time I pulled the plug on riding this bike to Sturgis.

Imagine for a second, the middle of July. Days were long and hot, and the Bikernet shop boiled with activity. The Sturgis deadline was fast approaching. I needed to plan stops, hotels, food funds and a place to stay in the Badlands. Then suddenly we were forced to shift gears. Actually, we took the planning process out of gear. One day, I scrambled for the finish line; the next I coasted. I couldn't find the stress switch for a week and relieve the pressure.

Most of my parts were baking in the Tony Pisano, Worco powder-coating ovens. It took me a week to realize the Sturgis Rally would survive without me, and I could relax. I was no longer under the gun to finish this build and risk my life riding an untested motorcycle halfway across the nation. Then it dawned on my feeble brain. I had a terrific opportunity to finish this bike and test it for a year before riding into the Mojave Desert and across several Indian reservations. Plus, I could kick back and enjoy the summer, pressure- free. I bought an ice-cold six-pack of Coronas, a couple of fresh limes and grabbed a sun tan. Not bad.

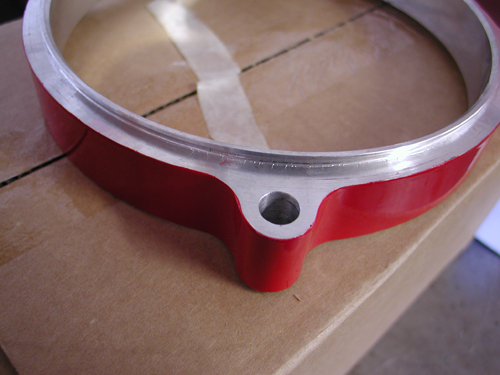

Tony is a pro powder-coater of the finest order and knows what it takes to tape off motor mounting plates and plug threaded holes. He saved long days under a grinding wheel. The powder work came out supreme. This year I tried something new. I powdered even the sheet metal, then asked a pro to paint panels on the tank and a flat black stripe down the Chica rear fender. He handled that aspect in a flash. Then I turned the job over to George the Wild Brush for the 5-Ball Racing logo on the tanks and pin-striping.

George drives around Los Angeles in an old Toyota truck with a camper shell, the home of paint headquarters. He folds down the tailgate, uncovers his vast, dripping assortment of paint and goes to work. He's old school to the bone. He pinstriped the giants' drag race funny cars in the '70s.

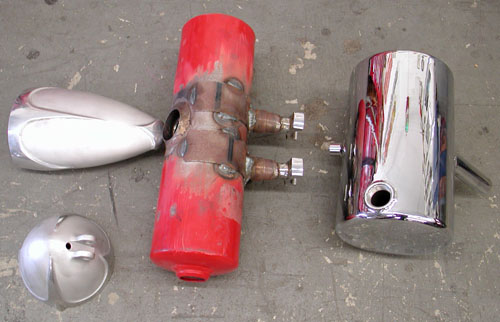

Here's where my fuck-ups began to surface. After the tanks were powder-coated, I decided to test them for leaks. I had planned to coat them with a sealer, and received Kreem tank sealer from Bikers Choice.

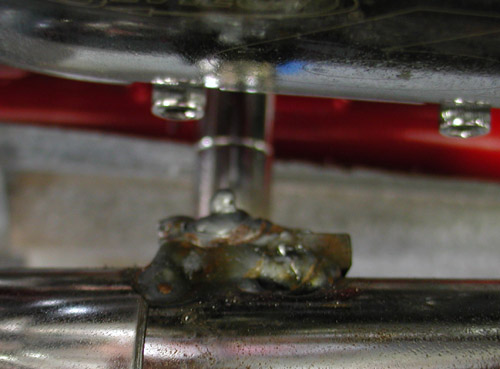

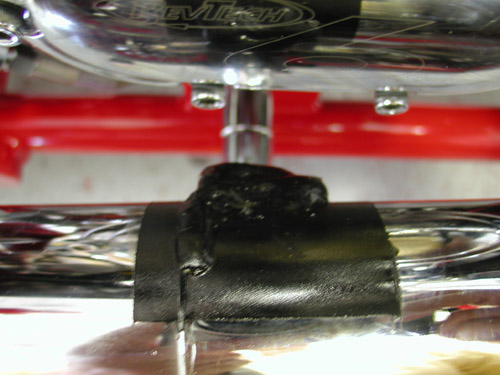

Here's the quandary: You can't seal tanks and then have them powder-coated. It might all go to hell in 400 degree ovens. So I held off. Then I decided to hit a local radiator shop for the test. We discovered one small leak where I welded in a rubber-mounting bung in the bottom. I ground it clear of paint and re-welded it. No problem. The painter touched it up for me. It was on the bottom of the tank and I was good to go. I thought.

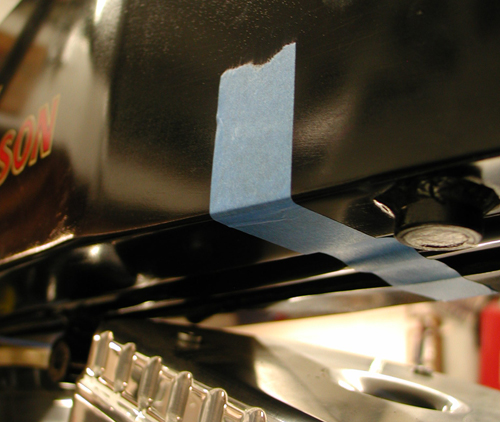

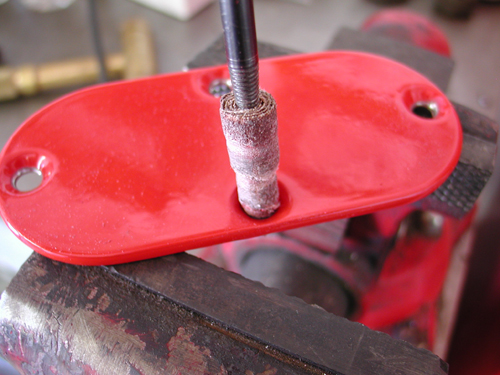

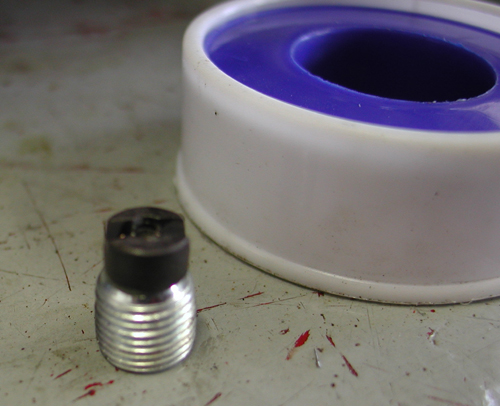

Next blunder: Instead of pressure-testing my handmade exhaust system, I decided to try another sealant available from Kreem and Bikers Choice. It's blue madness and can only be used on new pipes. I followed the directions, but it's a messy operation, and of course, I attempted this process for the first time, after I painted the pipes. What did I learn from these hiccups? Test tanks and pipes before you coat them with anything, period.

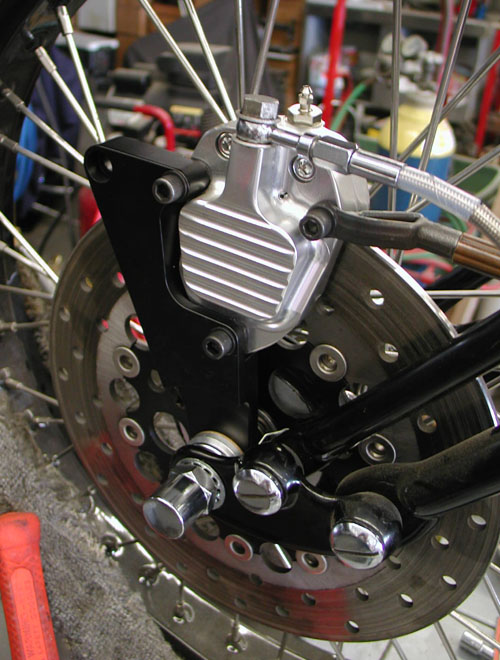

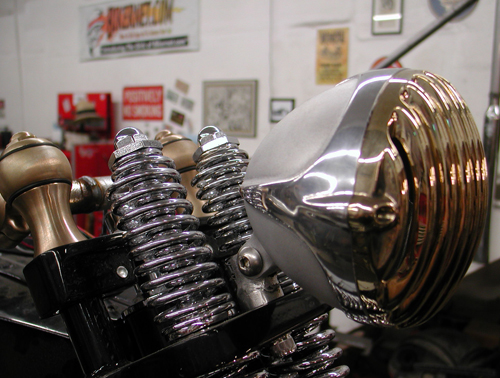

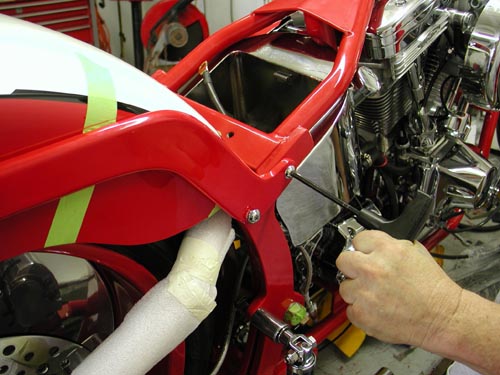

The first item to be installed was the new Paughco narrow, taper-legged springer front end. It slid right into place. If only I had four arms when I'm working in the shop alone. The front end already had the 23-inch Black Bike Wheel installed with a special Avon Tyre. I just needed to grapple with the front end, fasteners, bearings and top crown. No problem. I also installed the GMA front brake bracket and spaced the front wheel for the 14th time. It's a tight fit, and I need something art deco to mount on the front of the bracket. GMA, now owned by BDL, only builds a springer front brake bracket for the right side. I was forced to flip this one over. I could have machined the leading lip off, but I decided it could be used for some unique reflector, or quirky hood ornament. We'll see.

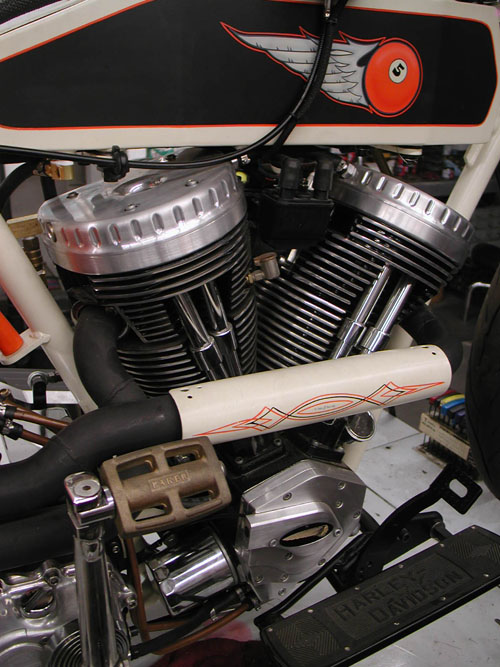

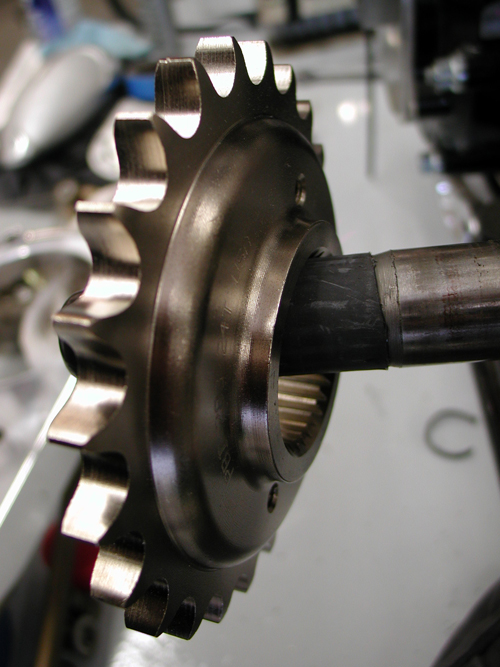

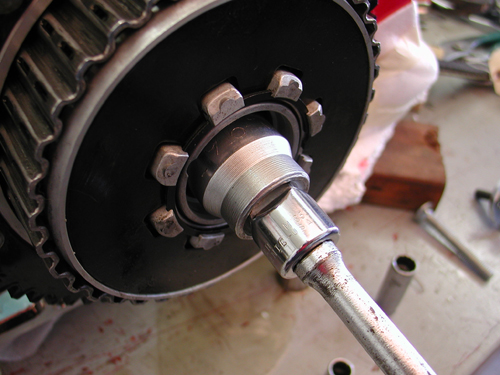

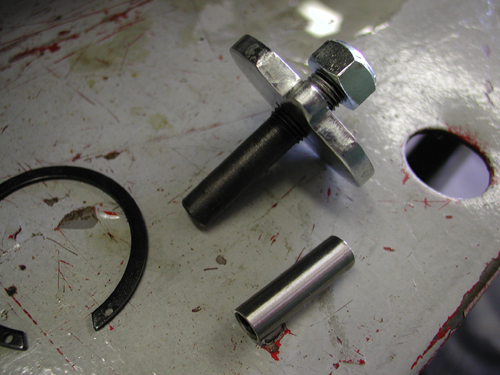

When I disassembled the bike, I carefully collected all the parts on this table. I also zip-locked all my fasteners and wrote their job descriptions on the back of each card. That was seriously helpful during assembly. Next, I dropped the Crazy Horse 100-inch engine in the Paughco frame, with the JIM's transmission and the Baker kicker system installed. Since the chain ran against a portion of the frame, I ordered a ½-inch 24-tooth tranny sprocket from JIMS and installed it with this special JIMS nut, designed with a built-in locking device. Unfortunately, no matter what I did, the holes wouldn't line up, so I safety wired the nut to the sprocket to prevent it from backing out.

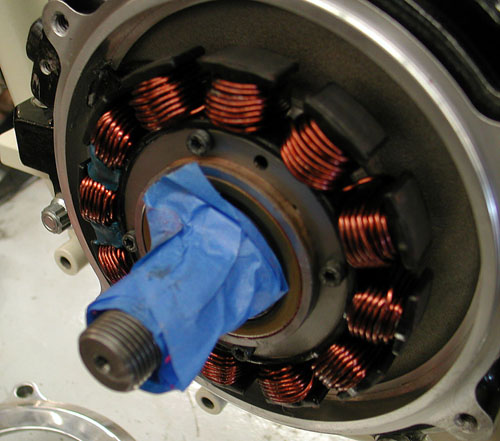

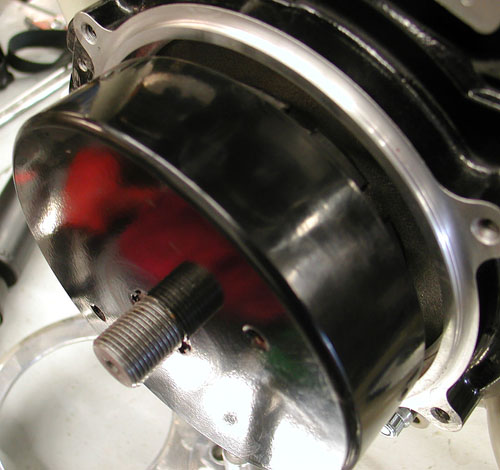

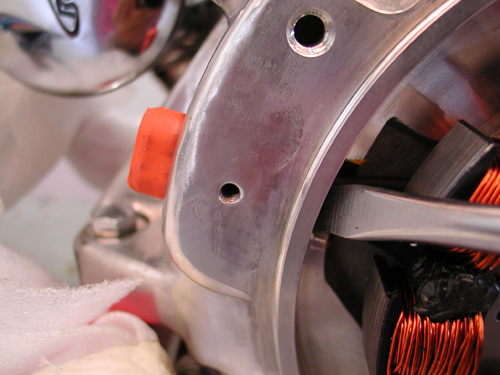

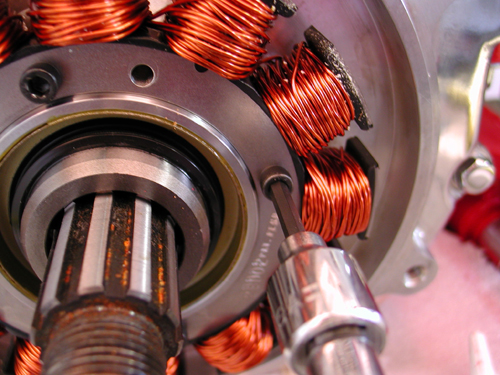

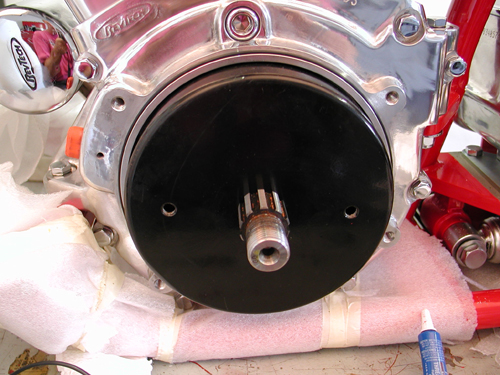

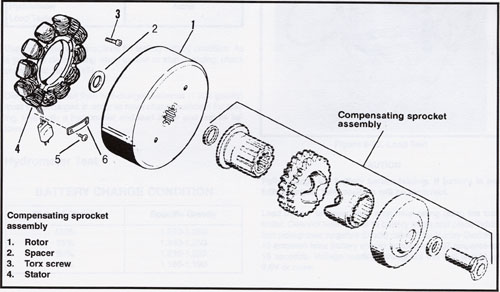

Then I faced one of the toughest assembly jobs, installing the Spyke alternator stator plug in the right engine case. It's easy and difficult at the same time. This time, I smeared the tunnel and the plug with Never Seize and tried to push the plug through the case tunnel. I also carefully backed out the set-screw and scraped any burrs of the case edges. That didn't help, but I ultimately wrestled it into place. I'm always careful of electrical connections, wiring, proper grounds, etc. Nothing leaves us alongside the road more often than electrical problems. So, I don't like pushing and prodding charging components.

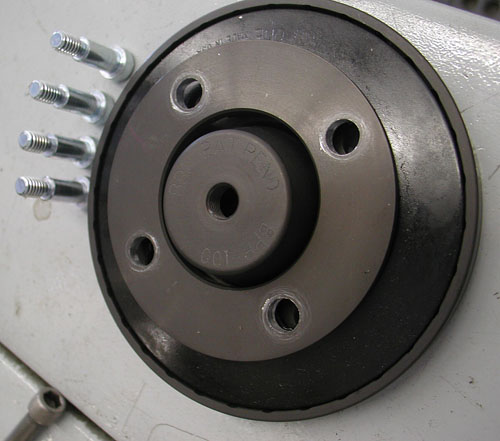

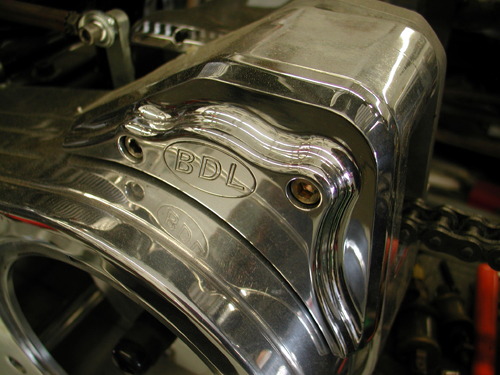

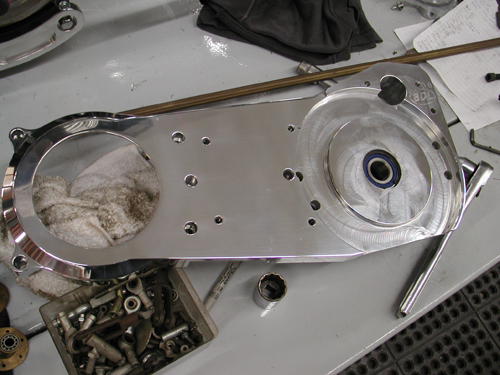

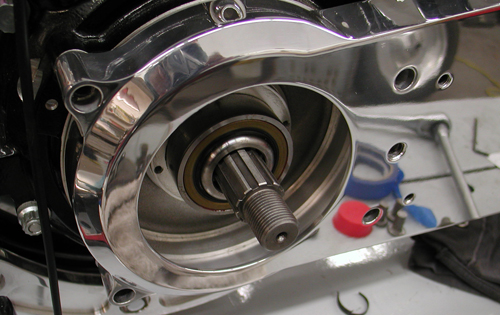

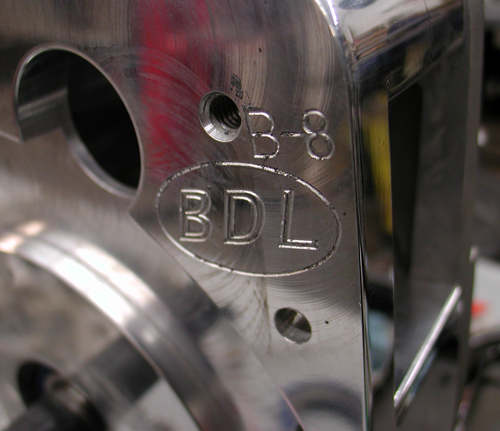

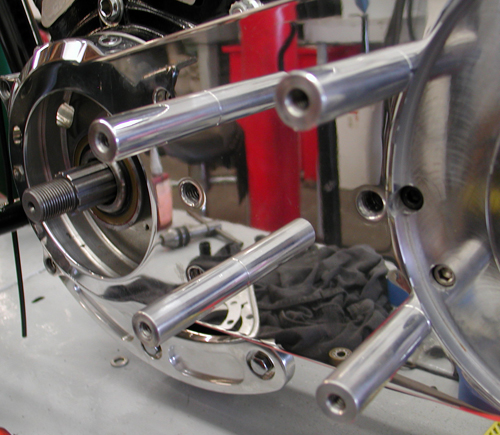

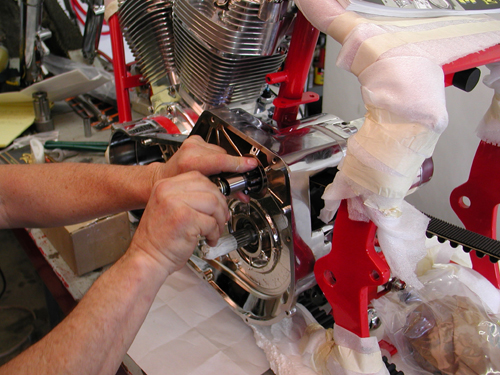

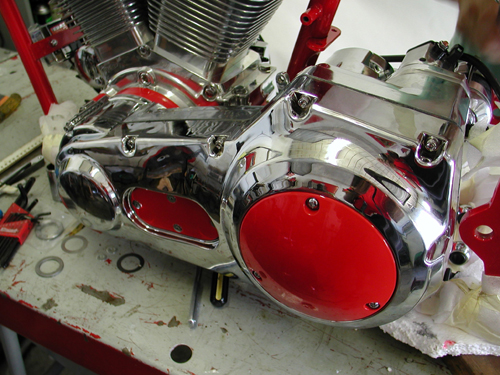

Once the stator was in place, I used self-locking fasteners from Harley-Davidson to fasten it down. Spyke is careful to supply all the proper assembly instructions, but it's always tough with aftermarket engines. Because it was somewhat of a guessing game, I installed the Spyke rotor a couple of times to make sure all the clearances were proper. Then I could move onto driveline alignment and the installation of the BDL narrow enclosed belt drive system.

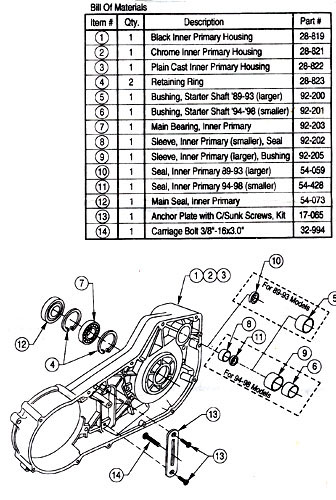

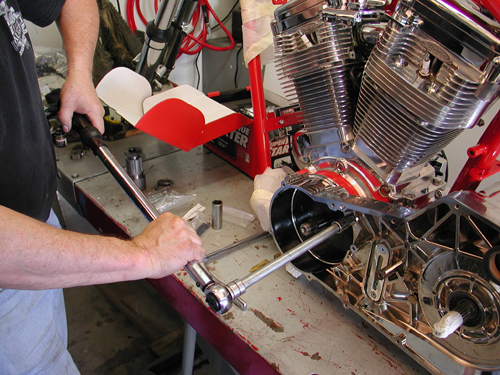

I've worked with BDL components for at least 15 years. They are solid as a rock. I used the inner primary to pull the engine and transmission into alignment. I left both major components loose in the frame until I pulled it up tight with the inner primary. Don't forget the John Reed Code. I use Never Seize on all bolts rolling into soft aluminum. John warned about damaging porous aluminum threads by running hardened steel against them over and over. Never Seize allows them to glide in and out of the cases without stress or abrasion.

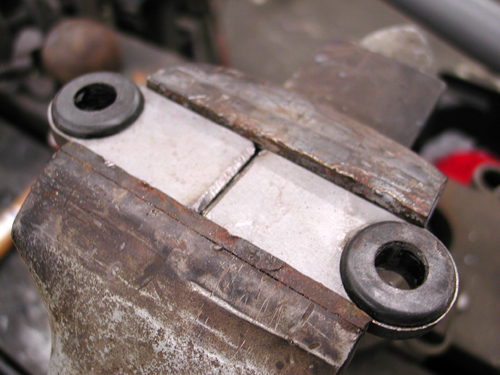

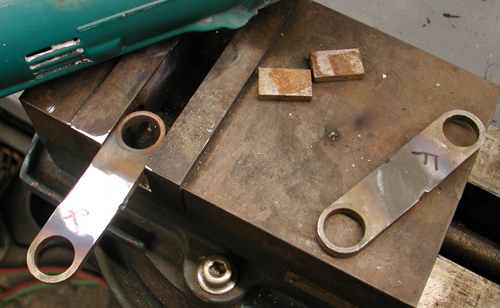

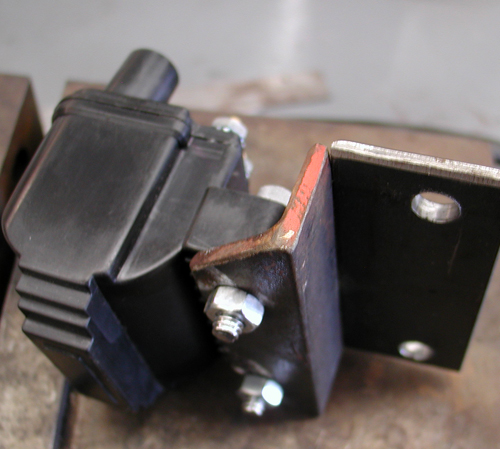

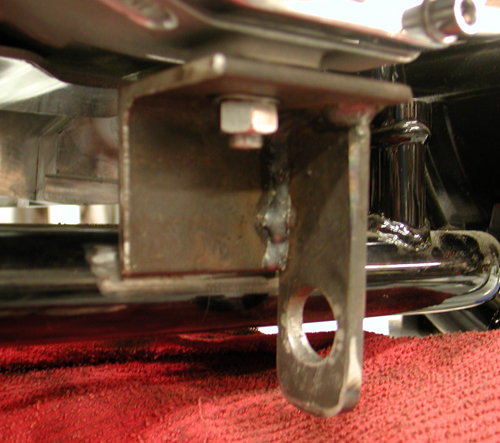

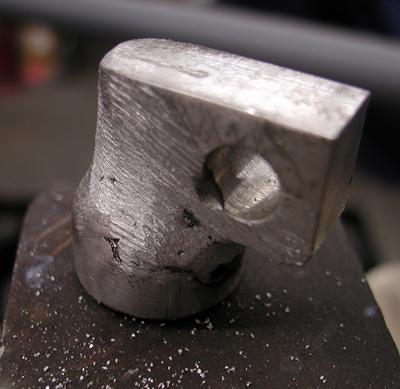

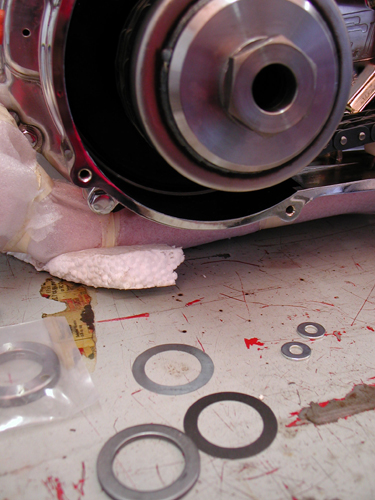

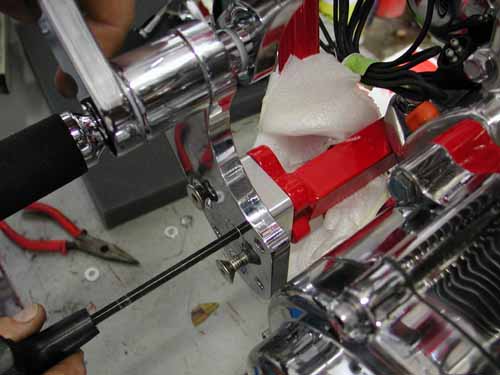

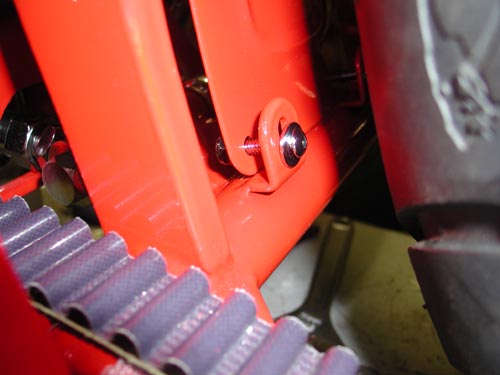

With the driveline aligned, I tightened down the rear engine mounts and then checked the front ones for gaps. I shimmed the front motor mount perfectly, then tightened it down.

Next, I focused on the transmission. The Paughco mounting plate was tight and the JIMS trans case was fine in the rear, but slightly elevated in the front. I dug around until I found the correct shim washers and drove them under the trans and around the front tranny studs. It's key to go through these motions for proper alignment and to save problems with the belt. It's surprising how easy the BDL system slips together if the driveline is aligned.

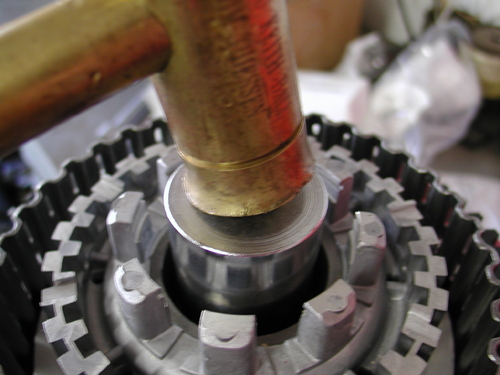

I followed the BDL instructions and bolted the engine shaft insert to the pulley then drove in the alignment pins and tightened down the Allen fasteners. I pulled the pressure plate pins out of the clutch and removed the clutch plates. With the clutch hub and the engine pulley holding the belt, I carefully slipped them on simultaneously. I attached the left-handed clutch nut and tightened it with an impact gun. I did the same with the engine main shaft nut. I turned over the engine and checked belt alignment and pulley alignment. I spaced out the front pulley slightly with a shim and was good to go.

BDL TECHNICIAN NOTE:I received a call from BDL, “You fucked up, Bandit,” Dan said. He pointed out how I didn't mention using Loctite on the transmission mainshaft splines when I installed the clutch basket. “That's more important than many folks realize,” he said. Vibration from the spines can tear up the basket splines and ultimately the clutch plates.

I generally don't Loctite the mainshaft splines until the bike is tried and true, encase I need to remove the clutch. “Harbor Freight sells a cheap vintage steering wheel puller,” Dan said. “They work like a champ for pulling BDL clutches. If a hub is too tight a little heat does the trick, melts the Loctite.”

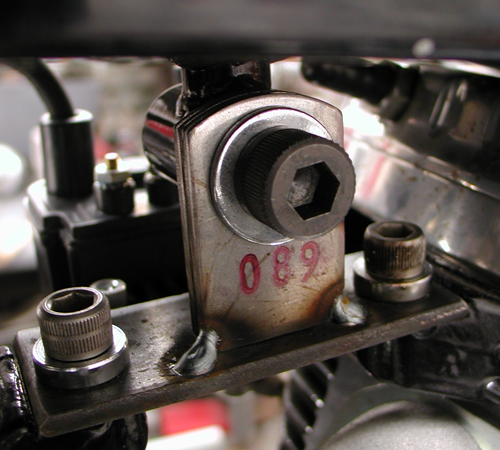

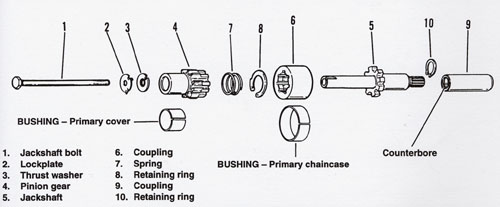

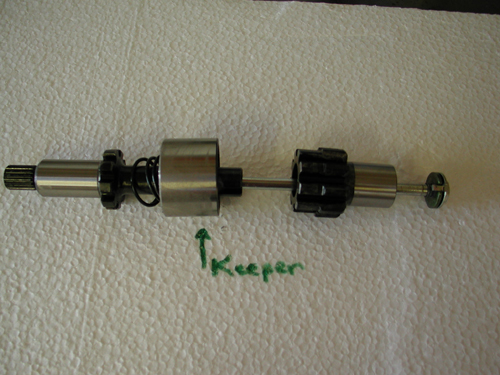

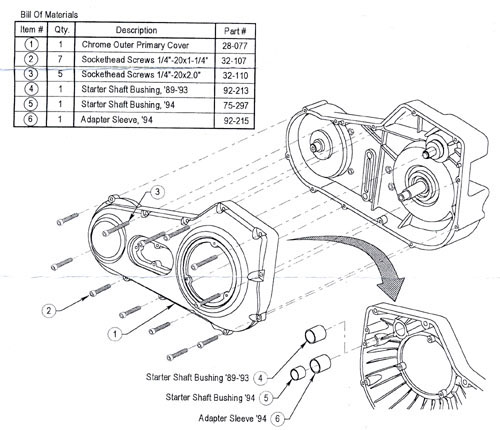

With the clutch back in place and all the elements tightened down I installed the Spyke starter and pinion shaft. Giggie, who just passed away the other day, told me years ago, how to check the spacing. To keep the starter strong and not fuck with the ring gear, the starter gear should rest about 0.150 back from the ring gear. Too close and it doesn't have the space to begin turning and jams against the ring gear. Too far receded and it won't make good solid teeth contact.

With the primary almost buttoned up, I moved to the LA Chop Rods new-fangled internal throttle installation. Internal throttles are cool but precarious. If a bike stumbles and falls over, the first damage is generally to the bars. It's easy to replace an external throttle or a grip. But what the hell. We're not building a bike to fall down.

About this time, the Sturgis event hit the summer calendar, and folks arrived from Australia for the ride. Doc from Heavy Duty Magazine, in Australia, picked up a Victory for the run. Nicole Brosing, an Australian tattoo artist, flew to the coast, rented the same Road King she rode last year, grabbed her girlfriend and split north to San Francisco then east to the Badlands.

I wrenched in the shop, drank Coronas, smiled and caught a sun tan. Gard Hollinger from LA Chop rods slapped extra engineering into his internal throttle system. His instructions were detailed, but I was still nervous as I attempted to determine the proper length. It's always a sharp notion to take the bike off the lift so the bars can rotate for testing the overall length. It's actually a breeze to install, although I honed out the bars slightly, for an easy slip. Gard devised the cable lock-down with a brass sleeve to prevent damage to the internal cable and afford a solid grip for the set screw. This throttle, with extra bearings, is smooth as silk.

Then I turned to the classic spark plug wires from Low Brow. This is a cool system and adds class to any ride. They come in a kit form with all the elements needed, except a roll of solder, flux, and a gun. It was a simple operation, but I actually mounted the coil a tad on the tight side to the underside of the tank. Fortunately it all fit. Make sure to slip the boots onto the wires before you solder the brass fittings into place. Lowbrow attaches the other ends before shipment.

I simply attached the spark plug wire to the spark plugs, ran the lines out of harm's way to the coil, added an inch for safety, cut the wires, trimmed them back for soldering, and crimped and soldered the fittings into place. Frank Kaisler told me to make sure to wipe all the flux off after soldering. So I did as Commander Kaisler instructed. He uses alcohol or solvent to clean the area, preventing future corrosion.

I took a day off to help Nyla's brother, Brad, build some diesel motor mounts for their 32-foot Cho Lee motor sailing vessel. They were smack in the middle of a complete restoration. It's a beautiful boat. I've sailed it to Catalina Island several times, when it belonged to an old friend of mine. Another deadline loomed. Less than a week away, the Easyriders Bike Show would rock the Broken Spoke Saloon in Sturgis. Bikernet sponsors the Panhead Class each year and I needed to create the trophy. Panhead Billy won the award. When I can reach him, we will feature his classic rat pan.

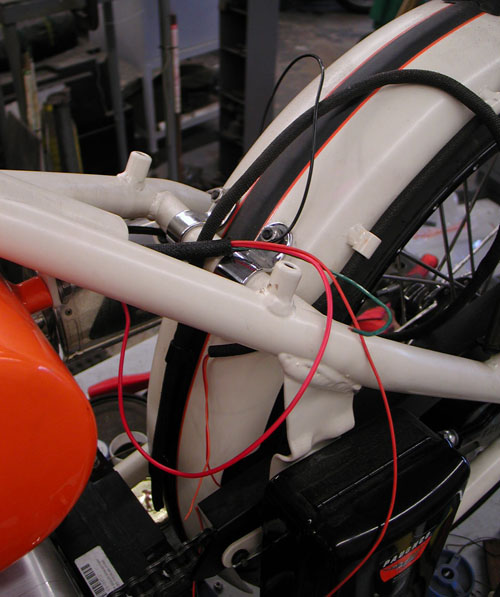

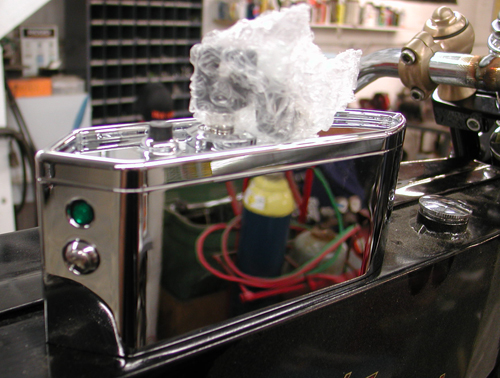

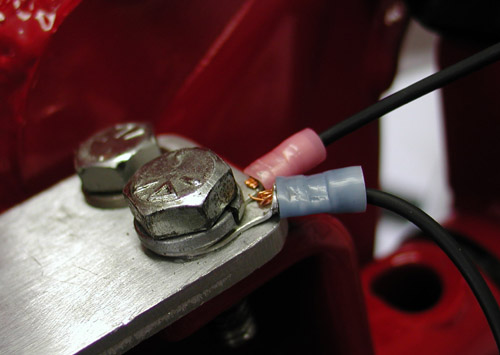

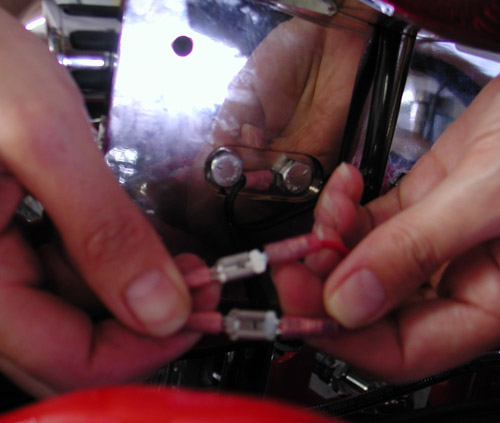

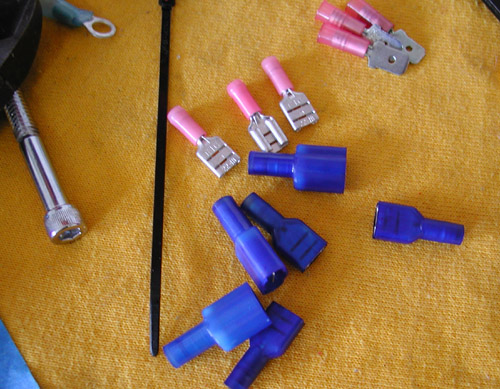

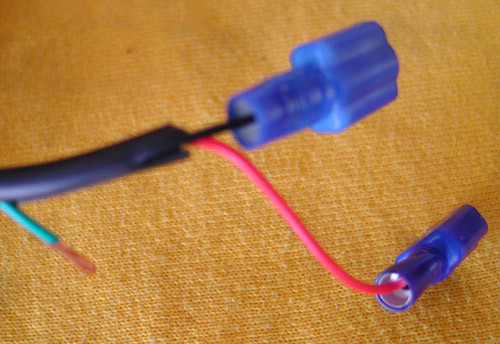

I shifted to the wiring. I used Phil's Speed Shop wiring system. It's designed for lots of custom applications and makes wiring a breeze. He includes instructions and a wiring diagram. The billet chromed box includes the ignition switch, the high-low beam switch, circuit breakers, starter relay, neutral light and starter button. I just ran the wires, used my Frank Kaisler soldering tool and ran the wires through the old H-D soaked canvas loom. I know that's not the correct term for it, but it's a close description.

I ran into one problem that held me up for weeks. I like the CrazyHorse bottle cap engines. They offer three ignition alternatives. First, the original Thunderheart unit, an adjustable timing Thunderheart, and finally a cone motor system. Unfortunately, they don't tell you enough about the stock system. I thought it was like a Compu-Fire system in the cone. It's a one piece unit. I reached out to other Crazy Horse engine builders who told me I needed a Thunderheart ignition module. So, I ordered the system from Thunderheart, but when it arrived it didn't jive with any wiring diagram I received from Thunderheart or Crazy Horse. It was a riot. Every time I received a wiring diagram or a box from Thunderheart, I thought I was good to go. Then some goddamn thing wouldn’t match, and everyone had split to the Badlands. I paced the garage waiting for answers.

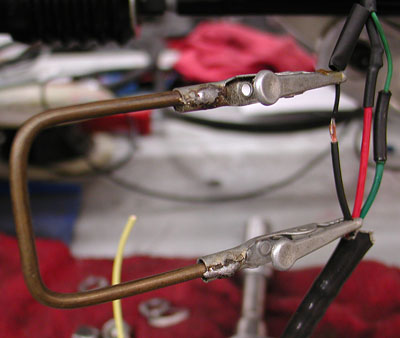

The Thunderheart tech guru sobered up after a week in the Broken Spoke swimming pool, doing belly shots with the lovely waitresses. He dropped me a simple e-mail: “There's only three wires goddamnit, black for ground, red for ignition and green to the coil. Go for a ride.”

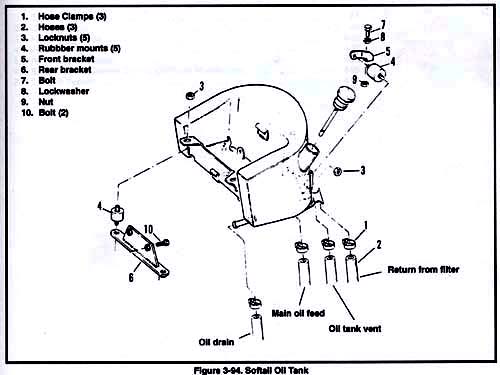

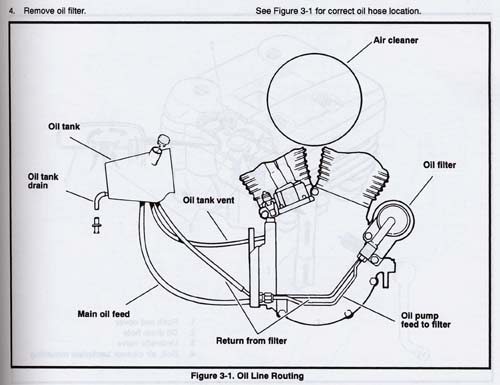

That solved that mysterious issue and I moved on. Three more puzzling obstacles surfaced. I cleaned the Paughco oil tank with solvent and small nuts and bolts. I counted the fasteners before I slipped them into the tank. It was sorta rusty, and I didn't want to roll without cleaning it. I poured a cup of oil in it and flushed it out. I hooked up the oil lines, and Crazy Horse sent me very specific instructions, but this will blow your mind. I couldn't figure out venting. I'll get back to that.

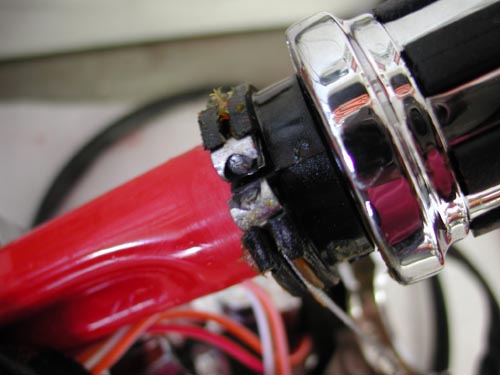

I hooked up my gas lines. I filled the tanks and one leaked. I threatened to fire myself on the spot and another challenge surfaced. The pinhole at the front of the tank, where I cut away a section to allow for fork stops, stuck out like a sore thumb. It was obvious, but we didn't spot it during testing. I called Jim Murillo, a professional painter and cried for assistance.

“Don't use Kreem, it peels,” he said. “Use Casewell two-part Phenol Lovolac System.”

I ordered some and their customer service was supreme for a small $36 order. Some companies get it, when it comes to taking care of customers. This is where tank seals become terrifying. I needed to kick my ass into the middle of tomorrow. Make sure your tanks are sealed before any finish is applied, including powder coating. I suppose I was over confident. What the hell.

The directions called for cleaning the tanks with lacquer thinner, nuts and bolts, sand, you name it. I tried the lacquer thinner and immediately fucked with George's pinstriping. I called him, panicked and drank whiskey heavily. Fortunately a Bikernet reader shipped me a fresh bottle of Bulliet Whiskey, and Dusty, one of the 5-Ball Racing Team Salt Flat members, hand-stripped several pounds of walnuts and shipped them out.

Incredible. I let the tank dry thoroughly, made up a small portion of the Casewell sealrant and poured it into the tank. I knew where the hole was, and fortunately it rested in an easy-to-reach corner. I tilted the tank in the sun and returned to the whiskey. George saved my ass once more.

With the tanks fixed and returned to the bike, all was well, and I put a key to the Phil's ignition switch for the first time. Here's another quirk. Crazy Horse doesn't tell you how to time your new 100-inch engine. It times itself. The bike didn't whine, growl, spit or cough. It fired immediately to life and purred. I checked the oil pressure, perfect. Then I unscrewed the cap off the oil bag to make sure the lubricant returned to the oil bag properly. Yep, it was returning, but the cap popped off into my hand. I wondered about venting. Everything was fine except for pressure in the oil bag.

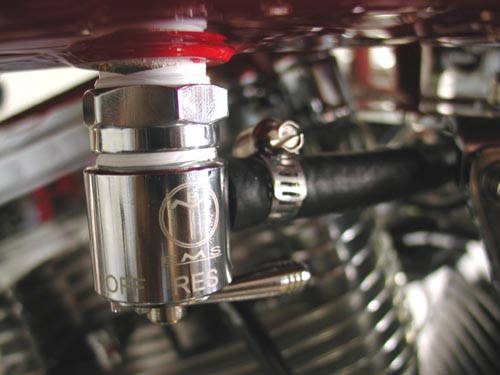

Again, I started a research project. The Crazy Horse installation material didn't mention a crankcase vent and I searched the engine. There are two 3/8-inch spigots between the heads, as if for a cross-over oil line. As it turns out they are designed as vents. I found out from Dar at Brass Balls that they just run a line under their gas tanks. I pulled one end, no oil flow. It had to be the vent, so I improvised and used another old machinery oil fitting to hold a screen to prevent crap from strolling back into the precious engine.

That solved that issue. I was ready to rock, but my seat hadn't arrived from Duane Ballard. It was a wild old sprung BMW seat he scored. When it finally arrived, it didn't fit. It was too high and too far back. I was faced with another quandary. If I moved the bars, I could barely place my boots on the footboards. I scratched my beard, looked at the box of walnuts, and then it dawned on me. Glenn Priddle, a leather seat master, who studied under classic saddle makers, made me a seat a couple of years ago for the 10th Anniversary of Bikernet. It was a wide, classic solo seat. I dug it out, dusted it off and it fit like a glove, dropped the seat height 2 inches and move the seat position forward 3 inches. It actually fit the frame better than the old classic from Duane. I dodged another bullet.

Every year when I build a bike, my mantra includes a solid, tough, rideable, unique bike that will last. But each year the unique project throws a few curveballs. It's part of my Zen education. Life is not meant for perfection. We need challenges to test our endurance levels and help us through the tough spots, find answers or solutions and persevere. Often my predicaments are caused by a lack of experience. For instance, if I ever use a Crazy Horse engine again, I'll know all the quirks and set-up issues.

Now, let's see if I can ride it for any distance. I would love to ride it to the Badlands next year or to Arizona for our Too Broke for Sturgis Run.

We'll see what happens next, as I take her through the Eddie Trotta break-in routine. Eddie starts a bike for the first time, let's her run and checks her over. Then he takes it out for a one-block jaunt, and checks it over again. Then he ventures forth for one mile and returns for another inspection, then 5 miles, then 25, then 50 and she's ready for a cross-country blast. Hang on!

Amazing Shrunken FXR–The Full Feature

By Robin Technologies |

Not long ago an issue of American Rider was devoted to lowered models contrived for shorter more compact riders. It was natural to feature a custom devoted to the tight-is-right crowd. In a custom world gone nuts with bigger, stretched, wider, fatter and pumped up motorcycles it was a lengthy chore for Buzz Buzzelli to find a bike designed for a concise, agile enthusiast. But fortunately after long arduous months, digging through one sordid garage after another, he discovered the only majestic model of it’s kind on the planet, the Bikernet.com Amazing Shrunken FXR. It was right in our own back yard. All he had to do was call me.

The bike was built by K. Randall Ball, of Bikernet and a writer for American Rider (the entire series of build stories are archived in the Bikernet Tech Area). “I generally build a bike every year to ride to Sturgis,” Ball said,

I’m too tall at 6’5″.” Pissed at the nasty notion that he couldn’t fly along desert highways into the red rock of Wyoming to sweep his same-time-next-year girl into his arms, he moved to build a dinky custom.

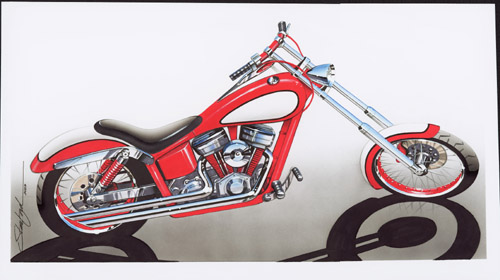

The bike was built to enhance the Rev Tech, 88-inch V-twin drive train and become the anti-big-bike representative. “So many bikes are long and fat, we decided to haul ass in the other direction.” There’s nothing like a small, tight custom bike, like Chica or the Zero guys build in Japan.

“We wanted to go in all different directions,” Ball added, “small rear wheel, black and chrome engine, no stretch and no passenger carrying elements.”

The Kenny Boyce Pro Street frame was modified by Dr. John in Anaheim, California. “The neck was dropped and shoved back toward the engine almost six inches,” Ball said. “We cut two inches out of the Pro Street swingarm and shaved off and tapered the fender struts.

In the process several talented sources were utilized to create the design and components. “We relied on Cyril Huze for most of the sheet metal,” Ball added. The rear fender originated as a Fatboy front fender modified to ride the swingarm as a unified component with the ability to remove it for repairs. The Bikernet crew including Dr. Terry the mad grinder bitch roughed out fender rails, sliced the Cyril Huze tank, modified the seat pan and nearly destroyed the Huze front bender. “He ain’t no Jesse James,” Ball said.

“A Hamster came to our rescue,” Ball said. There’s a talented worldwide group of builders called the Hamsters and one owns a structural steel shed in Harbor City, California. James Famighetti, who works I-beam forms for buildings, with his Brother Larry is actually incredibly talented with sheet metal and fabrication projects since both brothers ride with the group. “James took every bastardized element we created including the tank, front fender, rear fender rails, oil tank and seat pan and hand-formed them into works of art,” said Ball.

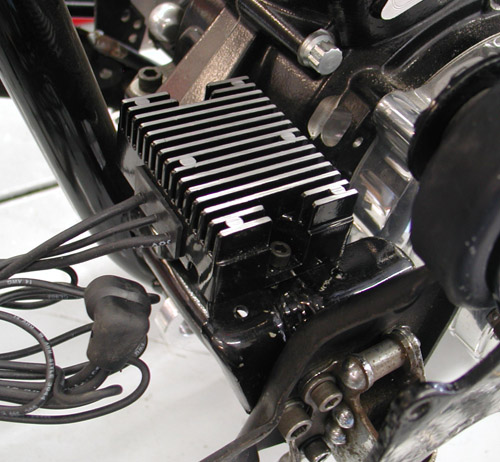

Electronically the bike took on the simplest form with the assistance of Giggie from Compu-Fire. “We installed a Compu-Fire charging system, starting assemblage and single fire ignition combination. Then we mated all the electronics around the Custom Chrome top motormount. Giggie also used the Compu-Fire machine shop to fabricated the mid controls for an even more compact motorcycle. Recently Giggie took his talents to the Rivera R&D department.

The final details included LePera’s seat upholstery, Harold Ponteralli’s teardrop paint scheme, crazy John’s machine tooled CCI brake calipers, Performance machine wheels with a 90/90/18 in front and a 150/70/18 Avon in the rear.

When completed and Buster hauled ass down the street the bike was trimmed of all frame elements on the downtubes and along the bottom of the frame on the right side to reveal the entire Rev Tech drive line. On the left only a Custom Chrome chromed, welded-on kickstand interrupts the frame flow around the BDL belt primary drive system. The pipes were hand made in the Bikernet Headquarters and only sprayed with flat black heat paint. The Front end is 39 mm narrow glide enhanced with black powder-coating and Joker machine trees and controls.

“I remember the first exhaust system,” Ball said, “and the sparks flying around the shop. While I wrenched Nuttboy, who is a college professor, ground the welds. Complacent, I twisted bolts and worked on the bike as hours passed.”

“We tossed those pipes in the trash and started over,” Ball added. “Dr. Terry was banned from the grinder.”

Okay, a short rider stock to custom comparison is in order. The seat height is 23 inches compared to the Softail Deluxe at 24.5 inches, the Buell CG at 28.5 inches, Dyna Low Rider at 25.5 inches and the new 883L at 26 inches. Overall length even with 38 degrees in the neck was 86 inches compared to the Sportster’s 90.3 inches, Dyna at 94 inches, the Softail’s 94.7 and the Buell Lightning series kicked the FXR’s ass with 76.2 inches.

Owner: K. Randall Ball, Bikernet.com

Where: Wilmington, California

Builders: Owner, Dr. Ladd Terry

Year and Model: 2004 Amazing Shrunken FXR

Fabrication: Owner/James Famighetti

Chrome: Long Beach Plating, Long Beach, California

Paint: Harold Pontarelli, H-D Performance, Vacaville, California and

Henry Figueroa (frame), San Pedro, California

Powder coating: Custom Powder Coating, Dallas, Texas

Color: Black with emerald tear drops

Year and model: 2003 Black and Chrome Rev Tech from Custom Chrome

Displacement: 88 cubic inches

Cases: Rev Tech

Flyweels: forged 4 1/4-inch stroke Rev Tech

Cylinders: Rev Tech

Pistons: forged 3 5/8-inch Rev Tech

Heads: Rev Tech

Cam: Andrews EV38

Valves: Nitrided stainless Rev Tech

Lifters: S&S solids kit

Oil Pump: Polished oil regulated Rev Tech

Heads: High flow Rev Tech

Carb: 45 mm Mikuni

Air Cleaner: Fantasy In Iron, Denver, Colorado

Exhaust: Hand made by Bandit

Ignition: Compu Fire single fire

Coils: Dual Dynas from Custom Chrome

Coil bracket: Custom Chrome with CCI ignition/starter switch

Transmission: 6-speed overdrive Rev Tech

Clutch: BDL

Primary Drive: BDL 3 inch belt

Final Drive: Custom Chrome belt

Rear Pulley: Custom Chrome Billet

Front Motormount: Billet by Paul Yaffee

Frame: Kenny Boyce Pro Street

Modifications: Neck cut and set back 4 inches

Rake: 38 degrees

Swingarm: Shortened 2 inches with CCI stainless axle plates

Front Forks: Joker Machine narrow glide

Risers: Custom Chrome

Rear Shocks: Short Progressive Suspension from CCI

Front Fender: Cyril Huze

Oil Tank: Cyril Huze

Gas tank: Cyril Huze modified by James Famaghetti

Rear Fender: Modified Fat Boy by Bandit

Hydraulic Lines: Good Ridge

Wheels: Performance Machine

Tires: front Avon 90/90/18, rear Avon 150/70/18

Brakes: Billet-6 piston from Custom Chrome engine turned by Crazy John

Brake rotors: H-D

Headlight: Custom Chrome

Taillight: Aeromach

Handlebars: Custom Chrome

Seat: Custom Le Pera

Speedo: None

Hand Controls: Joker Machine

Mirror: Aeromach

Foot controls: Handmade by Giggie at Compu-Fire

Pegs: Chrome Spur from Custom Chrome

Ignitions Switch: Bob McKay at CCI

Starter: Compu-Fire

Regulator: Compu-Fire

Alternator: Compu-Fire

Wiring: By Bandit

5-Ball Factory Racer, Part 7

By Robin Technologies |

It's resting on the tail end of June and I'm riding to Sturgis on 27th of July. I'm burnin' daylight. Assembly will begin this 4th of July weekend, if I don't party the whole weekend away. This tech will take you through all the final preparations for shipment to paint, since I'm avoiding chrome. In this case, we're hauling down this old school road with only flat powder coating and pinstriping from George the Wild Brush.

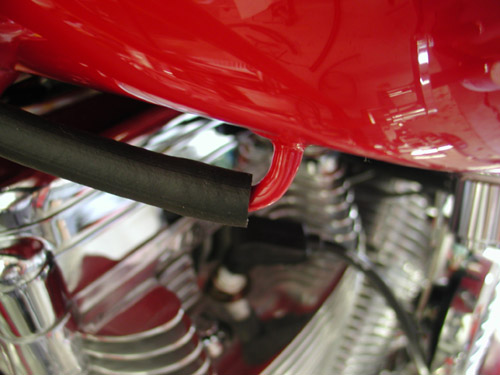

No bondo, hand-rubbed lacquer, heavy clear coats, just some pinstriping and graphics from the master will insure this vintage Factory Racer peels to the badlands. Let's kick this tech square in the ass with the basics. We will cover an Exile rear brake mounting, Paughco footboard bracket gussets, welded pipes, final mods to gas tanks, fork stops, LA ChopRods wiring guides, and some fender-wiring guides.

This is the stage of bike-building that's frustrating. It's the notorious time of little bullshit obstacles hindering progress at every turn. I need to clean and seal the tanks. I must hunt down a couple of vintage parts and FlatheadFern.com is helping. I need the parts painted before I can begin my Phil's Speed Shop wiring, but I need to relax. It will all come together, I say, brimming with confidence as I drink more whiskey.

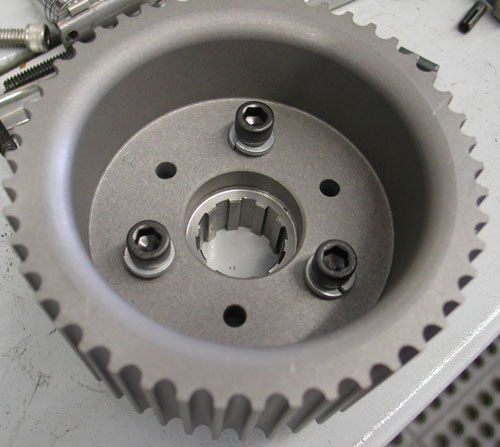

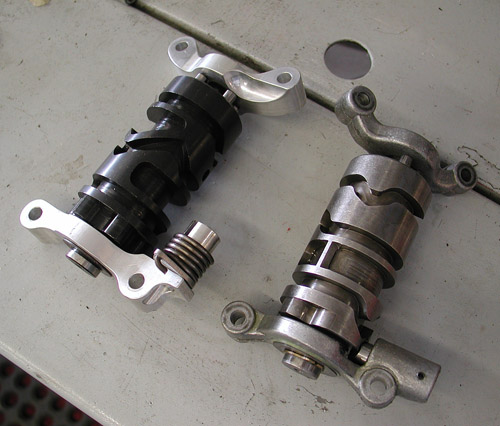

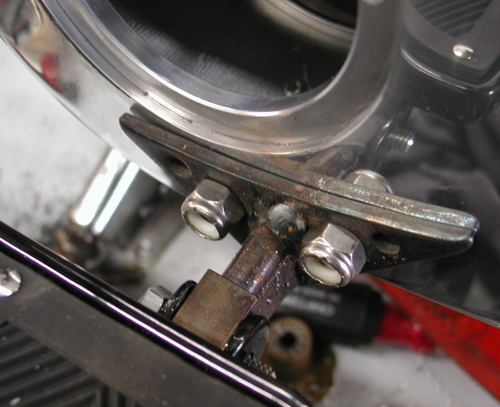

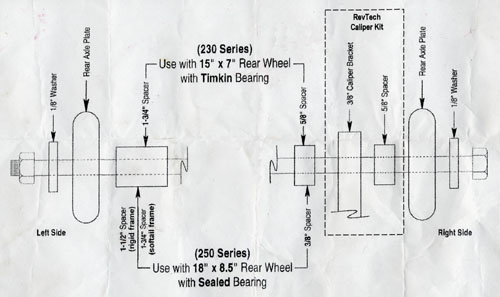

Let's get movin', so I can figure out what I'm missing as the weeks peel by, like deadlines to a Times sports writer. First, we installed the Exile black sprocket brake kit with a 48-tooth highly polished sprocket for the proper gearing.

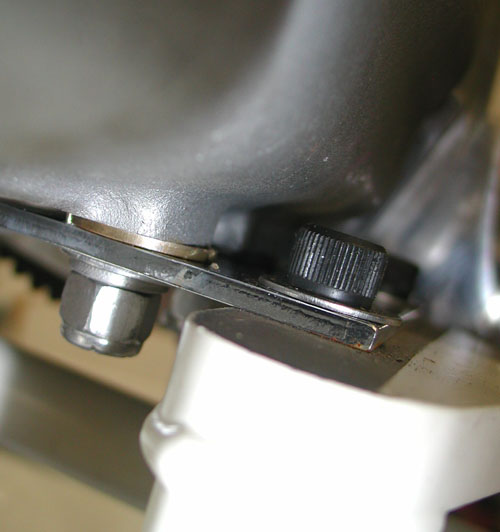

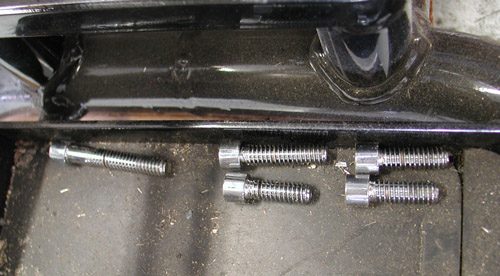

I dropped the special, chromed 7/16-inch supplied flathead screws on the deck. I bolted up the sprocket and prayed for alignment with the JIMS transmission sprocket, which was a ¼-inch offset. They distribute a number of trans sprockets with a variety of gearing and offsets from zip to 1 inch. I ordered another JIMS sprocket with ½ inch, since I feel it will afford me perfect alignment position. We'll see.

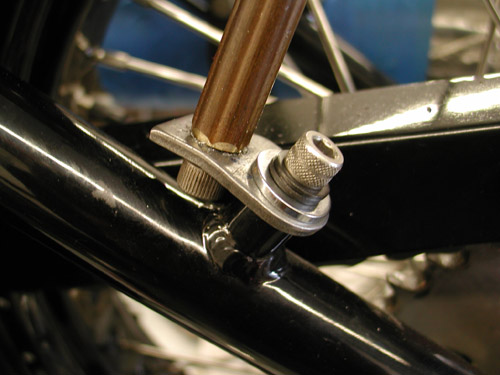

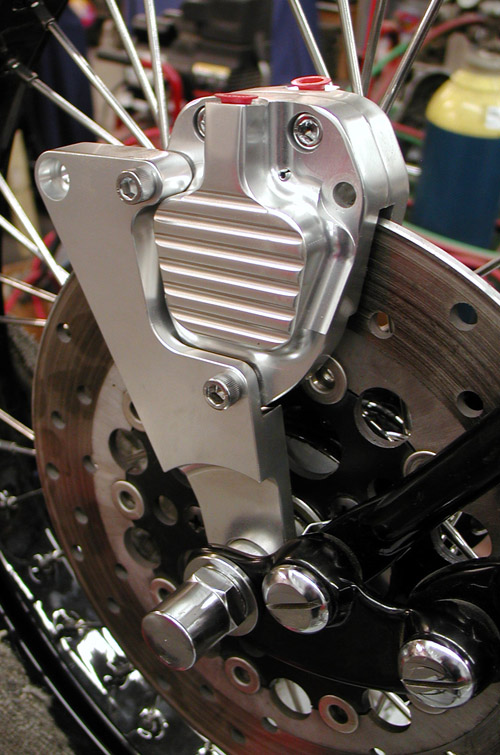

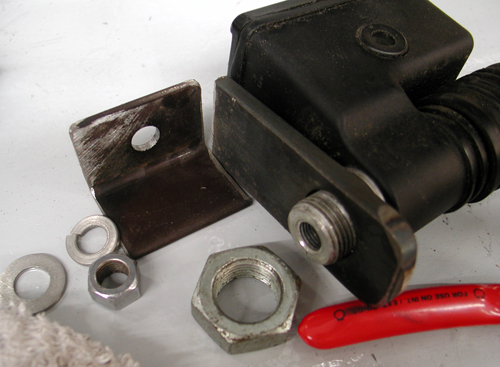

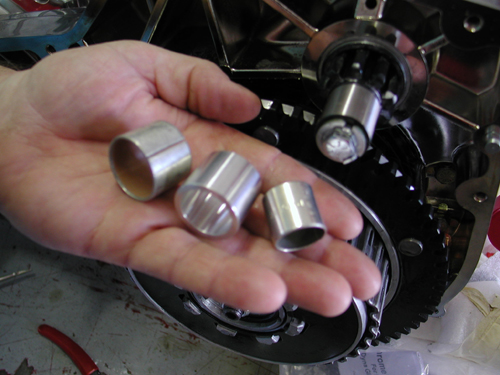

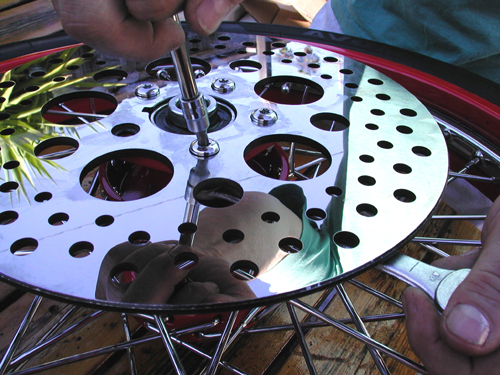

Russell Mitchell mentions in his Exile directions to consider a spacer between the hub and the Sprotor for alignment or tire clearance. The Black Bike wheel spacing seemed to be very cool.Next, Exile recommended machining the axle spacers so when the caliper and the bracket are installed and the axle nut is tightened, the caliper can run centered over the Sprotor.

I bored out the caliper bracket to allow it to float into the proper position over the axle spacer. Then I positioned the steel anchor tab against the frame. Exile supplied a fastener and a spacer for mounting, but I was able to weld the tab on the inside of the frame, very close to the caliper, which had its drawbacks. I also made sure there was some space and some chain adjustment space, so I wouldn't be caught without adjustment flexibility.

Russell made certain to point out that the tab needed to be absolutely parallel to the caliper, or braking efficiency will be hindered. He also pointed out the need to bleed the caliper before it was installed, but lifting it, so air could escape. I often take a file and slip it between the pads, to mirror the rotor surface. We'll get to bleeding over the weekend, I hope.

Moving right along, I spoke to Gard Hollinger like a panhandler at a coin convention. He offered a couple of his cable guide bungs for the project and I took him up on the notion. The code is to build a bike without using tie-wraps.

Gard makes a terrific product line of cable guides, tank bungs, and wiring loom guides. I crept through his shop slipping this guide and that runner into my pocket, and then I slithered out the back door.

I made a final speedo guide runner and tried to figure out my wiring system with the Phil's Speed Shop wiring harness. I tacked several loom runners and made some tubing runners for the fender.

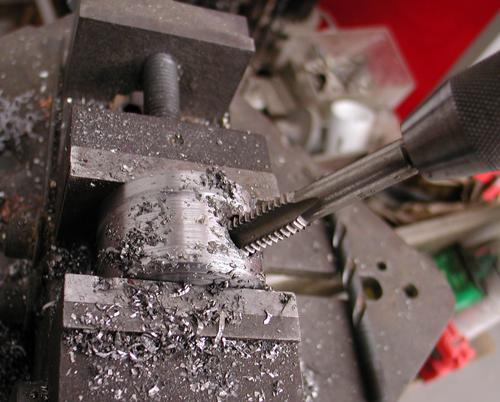

Then I moved onto installing the new and improved LA ChopRods internal throttle. They simplify handlebars and since no clutch lever was in the mix, my bars were destined for cleanliness. Gard, the boss of La ChopRods, the designer, welder, and janitor, went out of his way to redesign the LA ChopRods internal throttle with builders in mind. It has double bearings that won't fall out during installation. All the measurements were clean and simple, such as you cut a simple 4 inches off the bar and drill a tiny 9/64-inch hole just 1.5 inches in from the end and tap it to 8-32 thread. It was finished in a hot flash. I used an emery grinder on the inside of the bars to allow the internal throttle to slip in easy.

You can order the throttle cable from LA ChopRods. They recommend a Barnett 6B or similar universal throttle cable. They sell them in black vinyl or clear-coated stainless steel braid. In case I'm too harried to shoot the assembly, Gard suggests that the adjuster be collapsed and the cable installed in the carb first. He pointed out that the inner cable needed to protrude 1 11/16 inches beyond the outer cable.

Insert it into your bars and out the right end. Remove the screws holding the bearings in place and disassemble the ChopRods internal throttle. Gard designed a 3/4-inch brass sleeve to grab the internal cable and not damage it. In the past, I was concerned about screws coming loose and finding myself alongside the freeway. It happened to me on my way to the Exile open house. Gard made sure all the fasteners have no place to escape. And the handlebar fastener can be secured by running my GMA front brake lever clamp over the Allen 8-32 set screw. Done deal.

I ripped the Factory Racer apart after thoroughly thinking through the oil line placement, wiring, brake lines, and battery cables. I made a throttle guide and guesstimated it the best I could. With the bike in pieces, I finish-welded all the tabs and bungs in my sloppy MIG welding fashion. I drilled the frame for fork stops and busted the fender tab off the Paughco battery box. Positioned too close to the battery, I made another tab and welded it 3/16-inch closer to the fender. The head of the fastener won't rub against the battery. So far, it's the only item I forgot to weld completely. I missed the inside weld. Not sure what I will do, maybe panic. Maybe I'll grind away the fine Worco Powder Coating and weld it anyway. Or perhaps I'll just go for it.

In the next couple of weeks, I'll deliver on the Baker kicker system installation. What a fine piece this puppy is. Then you'll witness George “the Wild Brush” pinstriping various components and final assemble. Of course, you'll also experience the ride to Sturgis. Hang on.

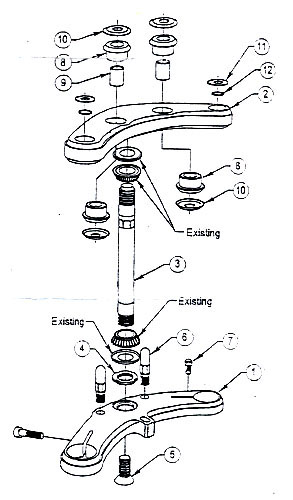

Amazing Shrunken FXR 11: Mid Controls

By Robin Technologies |

Shrunken FXR mid-controls by Giggie at Compu-Fire. Note: we need flat-headed Allens.

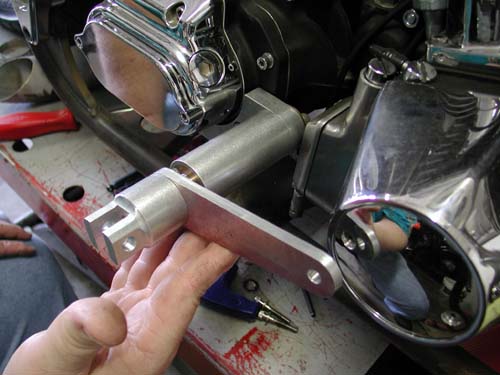

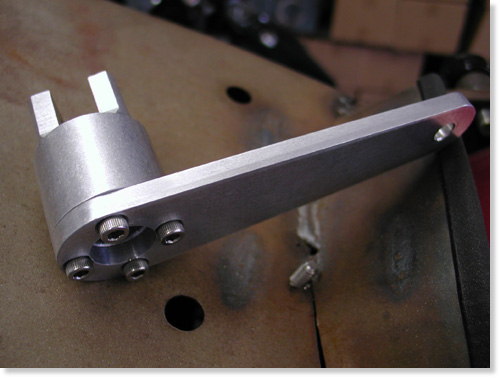

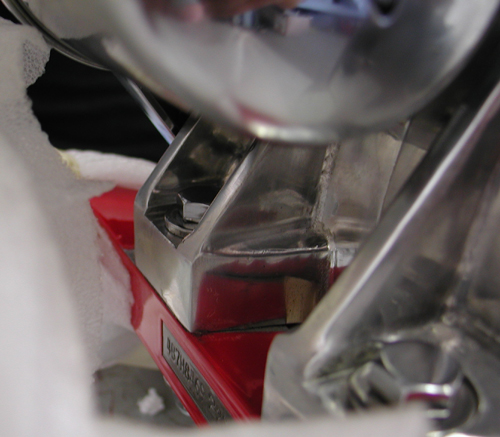

Giggie our master machinist from Compu-Fire rolled up to the Bikernet Headquarters last Saturday. We haven’t seen him for months due in part to his work on new starting systems for the custom market. They are dancing through the final development stages of a system configured to drive off the crank shaft of the motor with a 60- to-one ratio compared to stock 48-to-1. That will leave the area about the tranny available for custom applications or lower seat heights.

Giggie brought some wrong fasteners but lots of them and counter-sunk drilling tool.

Currently Compu-fire is soon to release a standard starting system, the Gen-2 HT, with 33 percent stronger magnets, 6-roller longer clutch (32 percent longer) with 30 percent more cranking while drawing the same amps from the battery.

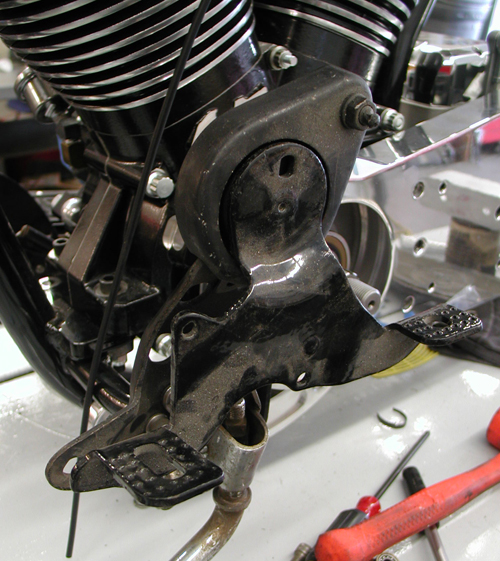

Here’s the tranny without the brake pedal components. There’s some tight tolerances going on.

I spoke to him about our cooling debate and here are some of his thoughts. “You want your oil to run at a minimum temp of 205 to eliminate water vapor or condensation that accumulates in oil,” Giggie said. “At 240 to 260 degrees petroleum based oils begin to break down, although synthetic lubricants could be good to 360 degrees. I have my doubts.”

Base bracket to be bolted to the transmission.

Giggie developed an oil cooler for his FLH that kicks on at 220 degrees and off at 200. It has an in-line thermal switch continuously reading oil temp. He installed his cooler in a box with vents and two small electric fans wired to the thermal switch (to cool while idling).

Giggie’s mounting bracket bolted in place.

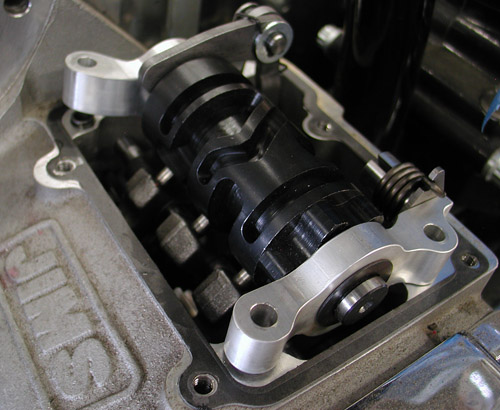

Regarding our project Giggie dropped off hand machined mid-controls for shifting and rear brakes. Next, we must buy a H-D slave cylinder with remote reservoir with a built in brake switch. We will hide the reservoir behind the oil bag and design a bracket to hold the slave under the trans.

This shows the pedal and shaft in the mounting bracket.

Giggie will supply us with four more bushings to run behind the shift and brake levers, two 1/8-inch thick and two 1/2-inch thick, to allow us variable spacing away from the engine pulley or point cover on the cone.

Giggie will supply two different bushing to be installed between the brake lever and the mounting sleeve. We’ll need the space to clear the point cover.

Unfortunately the sleeve hit the oil pump cover. We may be able to remove enough material or just polish the pump. The oil pump inlet fitting will also need to be turned down. It’s close.

With the bushings in hand we can develop our final linkage behind the BDL belt drive plate and Giggie’s tranny plate to connect with the slave piston.

In both cases we need to cut and machine the other end of the shaft, depending on the linkage.

I’ve decided to remanufacture the exhaust system which is now a tight fit around the new brake linkage. Giggie also machined the foot peg mounts to accept any standard, pivoting foot pegs.

The slick new mid controls for shifting slid through bushings machined into the BDL outter and inner covers.

Next we need the bushings, slave cylinder and a day in the garage hammering and welding a new set of pipes.

–Bandit

Back To Part 10, Page 2

5-Ball Factory Racer, Part 6

By Robin Technologies |

How do you feel about your computer? I could easily take my old .357 Smith and Wesson revolver and blow this sonuvabitch into the briny harbor Pacific waters. I'd set the smoking gun down, go find a job driving a trash truck, and be able to hang out with the bros and drink beer until my kidneys failed, then you could toss my carcass into the Pacific along with my IMac. Life is nuts.

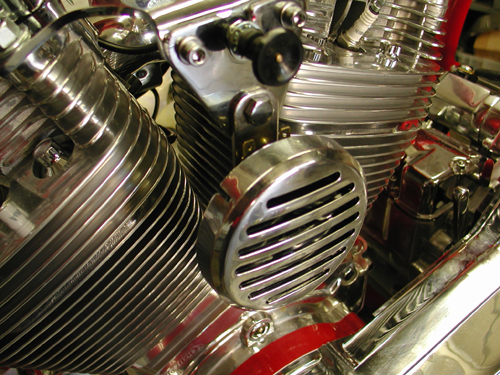

Ah, but the 5-Ball Factory Racer is coming right along. I hauled it down to Chica's for rear fender fitment, never thinking about the front fender. Should I? Chica makes his own wide ribbed fenders 5 and 6 inches wide. They're available for old tall 16-inch wheels and 18-inch wheels for an easy fitment to the tires. On my way south of Long Beach, California, I swung into Todd's Cycle. He was jammed with work. It's odd in this dour economy to see shops cookin'. Chica also was hustling to fill wheel orders, work on vintage bikes, and rebuild engines. I stopped in another shop on the edge of Long Beach, Richard Graves's car restoration facility. Damn, he does sharp work. He was working on a '50s Ariel square four.

Graves was also jammed with work, so the world ain't all doom and gloom. We just gotta provide a valuable service and be honorable businessmen, and we'll survive, goddamnit. Like Dave Rash, of D&D Exhaust says, “Motorcycles are mechanical Valiums. The world can go to shit, and the brothers take care of their motorcycles.”

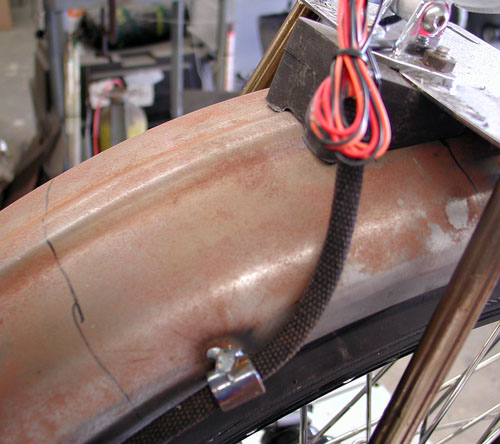

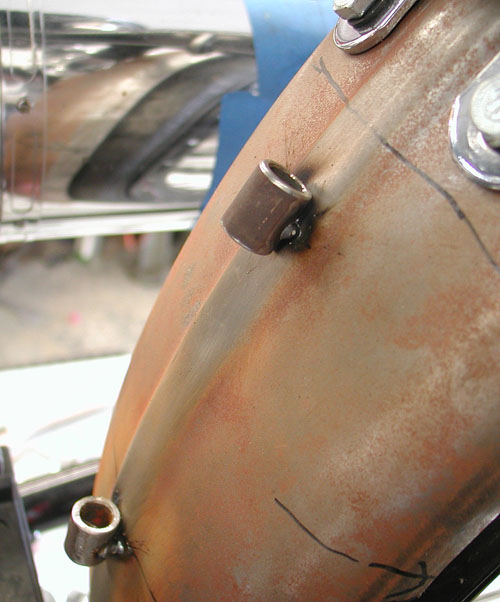

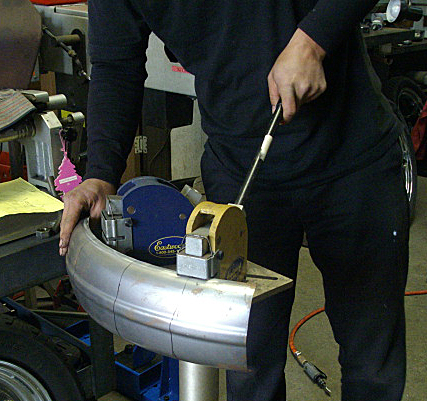

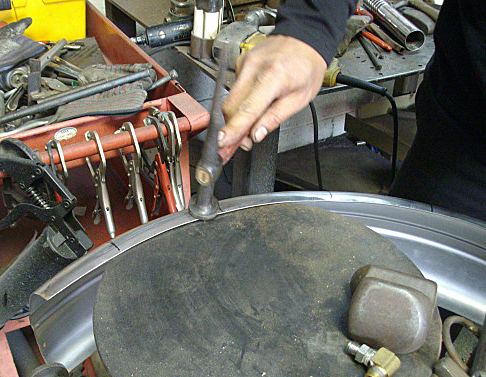

I like that notion. Chica marked my fender for stretching since his fender wouldn't wrap about a knockout Black Bike 23-inch wheel with an Avon Tyre. He indicated where the stretching would take place every 4-5 inches with a felt pen, then went to his machine. “You need to stretch it the same amount,” Chica explained, “and stagger the stretching maneuvers to prevent the fender from warping or twisting.”

I asked Chica if his fenders needed additional support where the fender rails would be attached. He pointed out that the extreme contours and the ribs added extra structural strength. But he did recommend two fender straps over the frame cross-member.

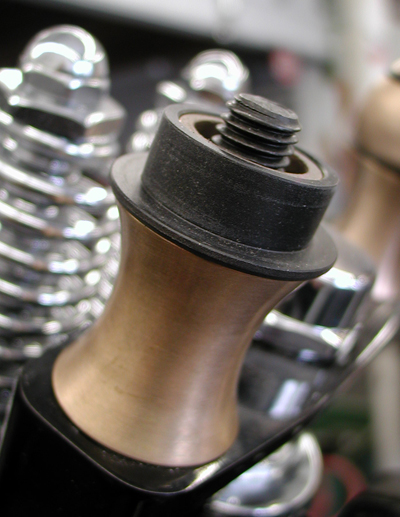

That did it, and Jeremiah and I loaded up the Racer for the return trip to the Bikernet Interplanetary Headquarters deep in the Wilmington ghetto. I started to work on the rear fender installation immediately. I bobbed it about 4 inches, but was grabbed by the rear wheel adjustment designed by Rick Krost of U.S. Choppers and manufactured by Paughco.

It's interesting, and I'm still getting the quirky hang of it. It automatically adjusts the ¾-inch axle back and forth, and up and down about ¾ inch. That element makes mounting the rear fender even more interesting. I was forced to don my patience- and-remain-flexible hat. Who knows if it's right, but I tried to work in several fender fluctuation means, so I could adjust it if necessary.

The fender was mounted with a single bolt at the bottom behind the battery case. Then, with the fender spaced evenly from the tire throughout the complete radius, I marked drilling holes for the fender straps. I drilled the holes, and the gods of stainless steel blessed my ass that day with a keen sense of accuracy. The holes and the fender straps lined up. I had to keep an eye on the axle adjustment, or the wheel was cocked right or left in the frame. “Ya gotta watch for the sweet spot,” Rick Krost said. I called him in the middle of the night to quiz him about wheel adjustment and alignment.

I also needed to make a spanner wrench for his axle adjusters. I was in a hurry one night and built a crappy one with some strange punched out flat open-end wrenches. I just heated, bent the tangs, and ground it to fit. It was sloppy, and ultimately, I built another one with brazed ¼-20 bolts to another wrench. It fits much better.

I also attached the Pauchco toolbox strap to the chain side of the bike, since the pipes would interfere on the right. It worked out perfectly for an additional installment point for the chain guard.

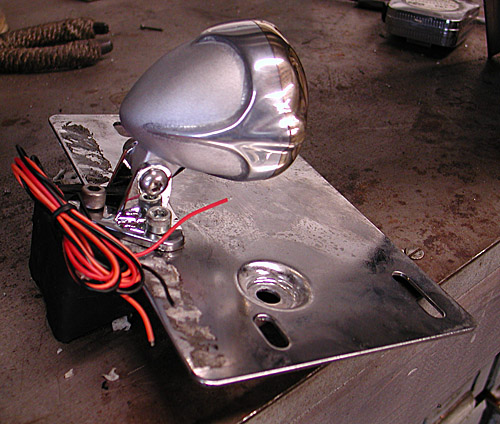

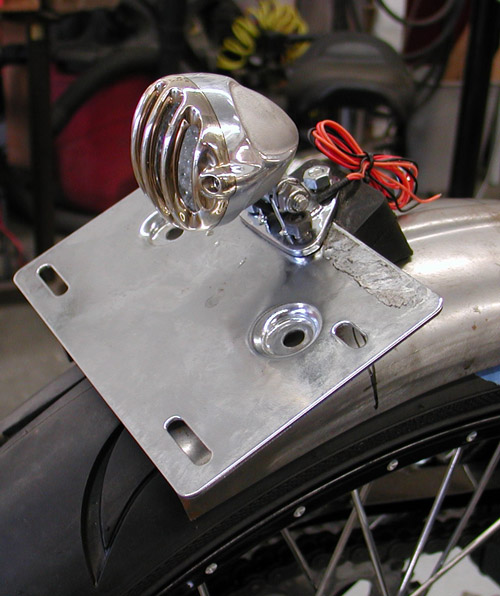

Next midnight run in the shop included grappling with mounting the Crime Scene taillight. It's a cool bastard, but I didn't have anything to mount it with. I dug through old boxes of parts, stock license plate rings, mounts, you name it, until I found an old rubber mount for license plate holders. It was already drilled for my three-point mounting taillight triangle. I found a thick license plate backing plate and went to work.

I drilled it to catch two of the Crime Scene holes and held the taillight over the license plate. I thought I had it made. I drilled the fender so the lip of the license plate will hang just slightly over it, for a proper, readable angle. Not sure I was successful. We'll see the first time I'm pulled over for speeding in Wyoming.

The one item I missed was the spacing for the bonaroo cool license plate ring. I'm not sure I didn't drill the holes too far into the plate, but I was thinking about strength and not bling. From that point, I moved to making fender rails. I can't do anything status quo. So I drilled corner holes in the backing plate, machined more brass, cloverleaf stock with 5/16 coarse threads and bent tabs and mounted them to the frame. Sorta crazy, but actually strong.

Evan at Power Plant Motorcycles on Melrose in Hollywood coached me on cutting threads in brass. “You need deep thick threads, so don't cut fine threads in brass,” Evan said. “It's soft.”

He also showed me a trick on his new antique lathe for centering cutting bits, which I'll never forget. I'll demonstrate in another tech in the near future. His shop was also busy, when I last stopped in. He builds vintage bobbers with very cool hand- made components. No CNC billet shit for Evan. Watch for his Chopper Challenge feature bike to show up on the pages of Cycle Source.

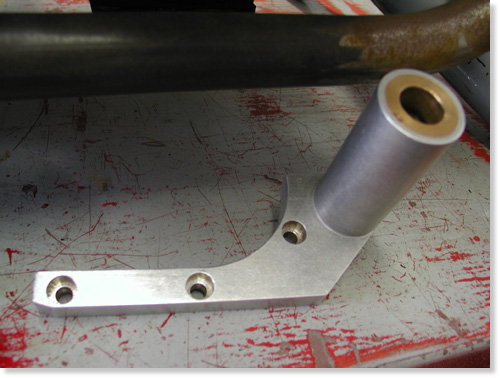

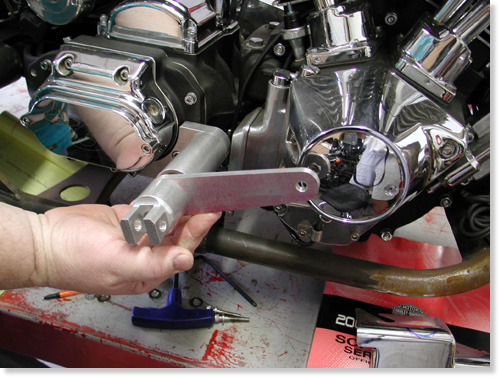

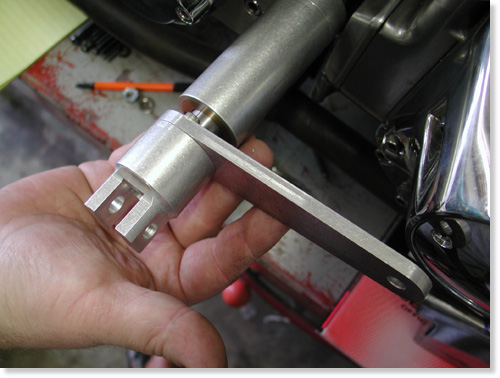

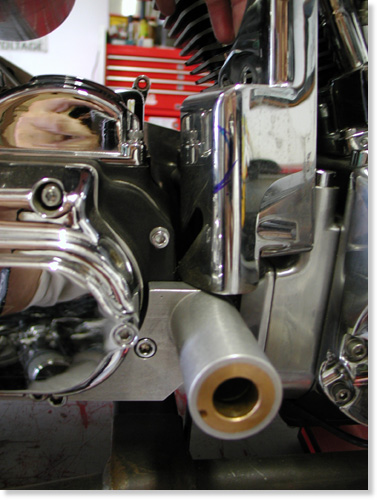

The guys at BDL helped with a super deal on a GMA front brake caliper, bracket, and hand lever. Unfortunately, they only make a springer bracket for the right side, so I modified for the left and built my linkage. Dealing with a narrow Paughco Springer and a front brake is a challenge to fit everything and center the caliper over the rotor. I still need to machine an axle spacer. I also need to deal with this billet bracket. I'm looking for some super cool art deco piece to bolt up front, like a hood ornament from an old Packard.

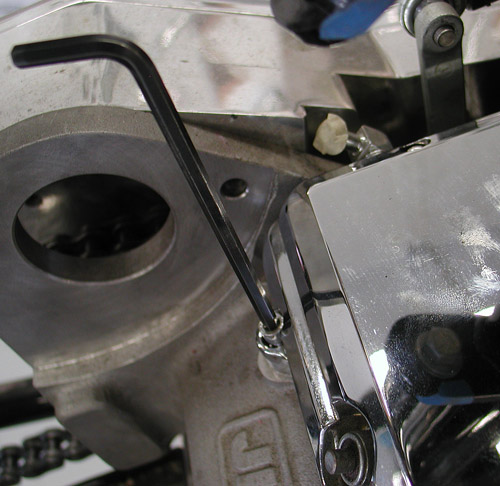

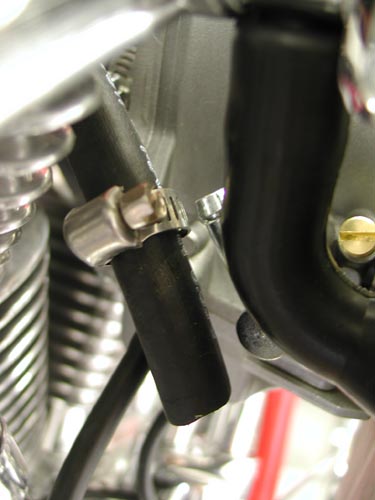

I had to deal with the suicide clutch situation. I had a vintage H-D rocker clutch system, minus the linkage and spring. I made the linkage with a spare Paughco toolbox-mounting bracket. Then while digging around, I discovered what I thought was a regulator mounting bracket. It would work perfectly for the regulator and had the space, and holes drilled for a clutch cable bracket. I went to work digging around for the perfect cable guide.

About this time, the Laughlin River Run surfaced and I rode my King into the desert. Two weeks later, I was called to duty on my Sturgis Shovelhead chopper to ride back into the desert to Cottonwood, Arizona for the Smoke Out. On the way I helped a couple broke down in the desert with a wiring problem. As we tinkered with his rigid Sportster, fulla devil tails welded everywhere like handles on wrought-iron furniture, I noticed his suicide clutch set up and his linkage and it gave me some good notions for a cable pinching system.

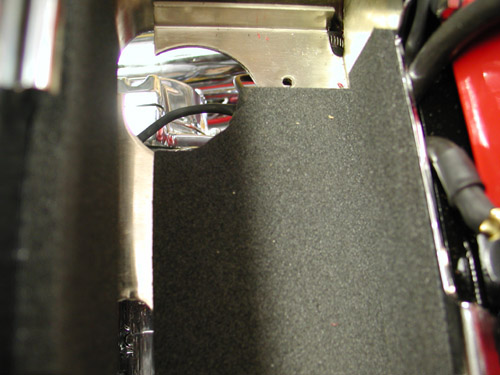

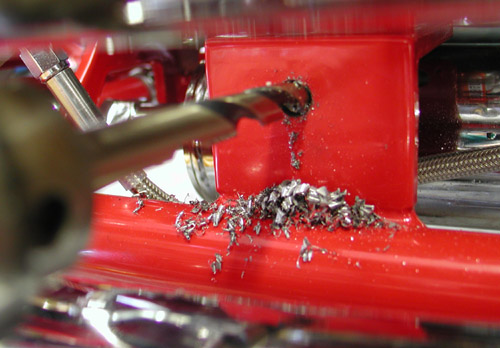

Between Laughlin and Cottonwood, I finally rolled around to cutting the front of the tanks to make room for fork stops with the Paughco narrow springer. As it stood the springer stops would smack the Factory Racer tanks, and my turning radius was shot. I went to work with a Makita cut- off saw and a plasma cutter to slice a new piece of 14-or 16-gauge steel for the replacement. The tanks were painted and that fucked with my MIG welding. Always clear the paint away from the welding area. The smoke from the heated paint messes with the pure oxygen and gas required for proper penetration. I'll work on that more with the next tank.

I'm getting close to making some final welds, while praying that a TIG welder will wander into my shop. But first, I needed to drop in the Baker N1 drum for 5-speeds. This is the simplest modification on earth. It's so easy even I could do it, amazing. These N1 drums… well I'll let Trish Horstman and James Simonelli tell you the facts:

Five years ago we developed the N1 drum for drag racers and street racerswho used our 6-speed overdrive. The N1 shift pattern (Neutral-1-2-3-4-5-6) wasdesigned to prevent false neutrals during aggressive 1-2 upshifts by positioningneutral under 1st.

The jockey shift/foot clutch crowd soon discovered the benefitsof the N1 pattern. The big lever ratio of a jockey shift lever desensitizes the feelof the detents in the transmission such that finding neutral is a crapshoot withbad odds. With neutral on bottom (or all the way forward), the jockey shifter canmindlessly tap all the way down to neutral thus allowing him to put both feet onthe ground as he rolls up to the stop light.

Today, a whole new crowd is realizing the benefits of the N1 pattern. Pingel’selectric shifter is slicker-than-snot and appeals to racers as well as those withrestricted movement in their left foot and left hand. Utilizing an N1 drum inconjunction with Pingel’s electric shifter makes finding neutral (with the solenoid)seamless, and yields a solenoid-actuated shift system that almost makes footshifting obsolete.

PN DESCRIPTION FITMENT

5-6QT-A N1 drum & pillow block assembly, 6-speed BAKER 6-spd overdrive except*

5-6QT-A1 N1 drum & pillow block assembly, 6-speed *Old 6-into-4 (S&S case) &Frankentranny

124-OD6RN1-A N1 drum & pillow block assembly, 6-speed RSD right-side Drive 6-speed, 2ndgeneration

124-DD6N1 N1 drum & pillow block assembly, DD6 DD6, all

2-5R-N1 N1 drum & pillow block assembly, 5-speed Single pole neutral switch 5-spds

2-5RL-N1 N1 drum & pillow block assembly, 5-speed Double pole neutral switch 5-spds

FEATURES/NOTES:

– N1 shift system option available at no additional cost with purchase of a complete transmissionor builder’s kit

– 5-speed N1 shift systems fit H-D 5-speeds and BAKER 5-speeds

– For aggressive shifting we also recommend the use of our anti-overshift ratchet pawl, PN555-56A for 5-speeds through 1999 and 555-56L for 5-speeds 2000-up. For example, this pawlmechanically prevents an unintended 1-3 up shift during an intended 1-2 upshift

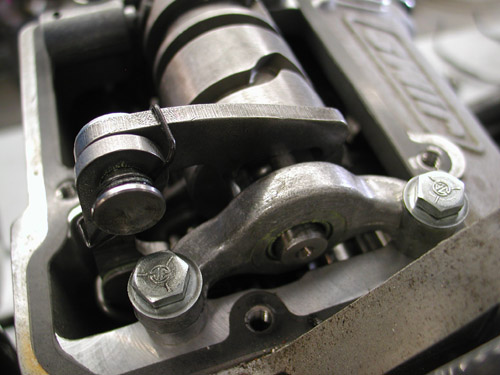

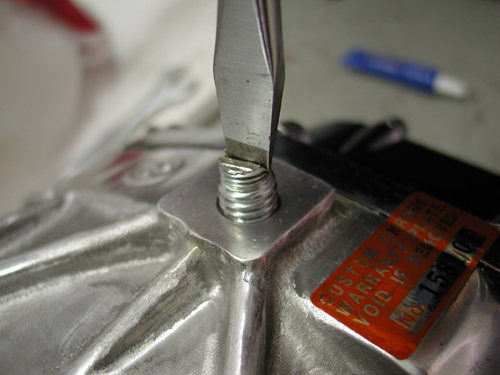

Okay, so I popped off the ¼-20 Allens off the top of the tranny cap. Since, within five fasteners there were three sizes, I placed them neatly in the battery pan to prevent mixing up the formula. The lid came right off.

Then the four 7/16 hex heads need to be removed and the drum and pillow blocks came off as a single unit. Don't forget to lift the shifting arm, and keep it up when you replace the drum.

It might feel slightly snug to remove since there are guide inserts pressed into the case to hold the drum perfectly aligned. I studied the drum as I removed it and set it in exactly the same position on the bench to insure I put the new N1 drum back exactly the same way.

I told myself the old mechanic's rule as I replaced the drum and aligned the shifting forks: Don't force anything, jackass. I carefully aligned the shifting forks, then made sure the pillow blocks fit comfortable over the inserts before rolling the fasteners back into place and torquing them to 130 inch pound of torque or 10.8 foot pounds.

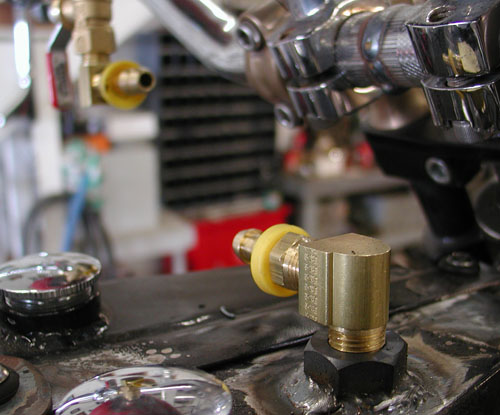

I smeared a dab of tranny oil on the lip of the transmission lid and slipped it into place, then tightened the fasteners to 130-inch pounds of torque. Oh, I forgot. I replaced the standard vent with something brass, mechanical, and vintage. What the hell. I'm going for that vintage appearance.

That's it for this installment. Next, I will install an Exile sprotor rear brake and 48-tooth sprocket. I'll finish all my welds, strip her down, and head to powder coating and paint. I have the color scheme down. It's going to be wild. I've also promised not to hit any more events between now and Sturgis for maximum shop time. We'll see if I run out of whiskey and women or not. Hang on.

5-Ball Factory Racer Part 3

By Robin Technologies |

I'm in a daze this morning. Too much Quervo Gold last night and too many discussions about the sinking economy. It's a bastard when they lay off port crane operators. What does that tell you? I don't want to go there on this dank gray morning. It's warm outside, but even the dogs, Tank and Cash, feel the gray skies. They look hung-over, droopy and drained. I haven't shaved in a couple of days, need a shower and a kick-my-butt workout.

All the women left me and ran off to the mountains this weekend. I know why Sin Wu needed a break. Have you ever tried to maintain a 10,000 square-foot, old dilapidated building, clean and care for two lumbering, sloppy dogs, two house cats, and a stray that wanders through and bitches if the food supply isn't consistent with her desires? The Macaw needs to be fed and moved into and out of the sun at the end of the day and now we have a fuckin' fish.

There are also construction workers, electricians and plumbers to deal with. It's never a dull moment around here. I'm a big proponent of running off all the costly pets, who can't do except shit and care for a half dozen concrete gargoyles. At least they keep the evil spirits at bay and involve zero upkeep.

Okay, I'll get to the tech. I was on a hunt for a vintage seat and Duane Ballard stopped by with this vintage BMW seat. I used chunks of wood to hold it in place while I pondered the little Hispanic girl who works at Shamrocks, the Mexican fish market two blocks away. Since the seat was made with a number of springs incorporated in the structure, I didn't feel additional springs were necessary. I played with my options, but nothing – graceful, stylish, art deco or vintage – came to mind. Then I grabbed the springs that came with the prototype Paugho frame and voila, it all came together using the existing frame bungs, the mini-seat shocks and a slight modification to the BMW seat.

I drilled new holes in the brackets and cut about 4 inches off the arms. The front of the seat bolted directly to the Paughco seat hinge and I was good to go. Duane stopped by again, blessed my creation, and took the seat for top-notch leather upholstery action. He's the best.

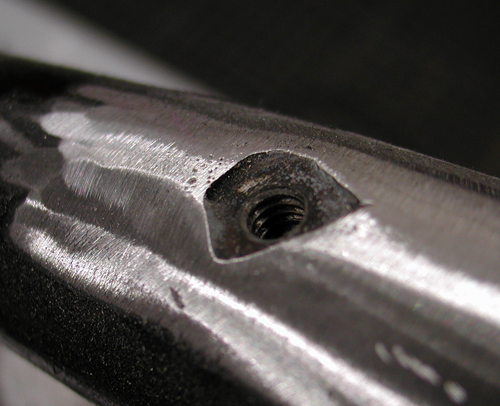

I shifted to my shift linkage system and called Jeremiah for the mathematical configuration from the system we build for his bobber. I wanted a tank shift and had several strange components, plus heavy, solid cloverleaf brass rod to use. I don't have any idea how I come up with this shit, but what the hell. It has class.

According to Jeremiah, from the pivot point down, the shift arm was about 6 inches in length, and the distance to the shift knob up was almost three times that length. That made for a vast throw and I needed to make sure I was clear, fore and aft, for shifting without smacking the bars or anything else. I checked my '48 Panhead with stock jockey shifting and the ratio was closer to two to one. In addition, jockey shifting is a different animal. There's no back and forth spring action on vintage tank-shifted bikes. The shifter banged through one gear after another from first to fourth, done deal.

That's the reason jockey-shifted bikes are best with jockey top transmissions. If you need neutral, just pop it out of any gear and you're back in neutral. Ratchet tops force you to bang through one gear after another down to the only neutral between first and second, often missing it. In our next tech, we will install a Baker 5-and-1 drum in this transmission to afford neutral at the bottom for easy reach.

Okay, so back to the job at hand. I'm trying to use as much brass on this bike as possible, so I dug through drawers and boxes of old machined parts and trinkets and came up with these brass-bearing supports. Then I machined a piece to fit these, then the axle piece to mount to the frame. Then I had to bore and tap the pivot, drill and tap to anchor the brass bushing, drill and tap to create a pivot stop and machine and thread the brass rods, plus machine an end to fit a heim joint connection to the transmission shift linkage. I spent hours tinkering and figuring, drilling, tapping and testing, and I'm reasonable sure I have a tough, working shifting system.

Then I shifted to the dreaded tanks. The tanks are fine, but more involved than normal one-piece, bolt-on tanks, ready with bungs for rubber mounting. Since this was a prototype Paughco Factory Racer frame, the first one of the batch, they bolted the tanks to the frame by drilling and tapping the top frame tube. Problem is, that afforded each 5/16 coarse bolt about three threads in mild steel tubing. In just a matter of time, those threads would fail, the tanks would rattle and come loose.

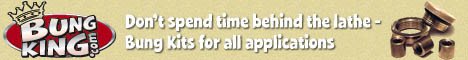

I decided I wanted to strengthen the tank mounting for the long road. I ordered some ¼-inch bungs, ¾-inch deep for a lasting hold. Later, I discovered that since the mainframe strut was 1.5 inch tubing, I could have used the 1.5-inch deep bungs from the Bung King (check their site for all available variations). I needed to re-drill the holes to a larger diameter for the bungs to slip into the frame. Adding the bungs and welding them enhanced the strength of the frame. At first, I though about machining a bung with a lip on it, but the tanks didn't have the clearance above the frame for a lip.

After drilling the frame holes, I tapped the bungs into the hole and as far below the surface as possible for the strongest, deepest weld. I would also need to grind off any protruding weld so the tanks would fit again. One tank protruded into the frame and rubbed at the back, so I moved it as far forward as possible for clearance, which amounted to about ¼ inch.

With the bungs in place, welded and ground, I grappled with the tank mounting holes. I thought I had it made, since I was dropping from 5/16-inch bolts to ¼-inch, but not so. Only one hole lined up. I grappled with these bastards for hours. Then I gas-welded the hole slots, refilled them and ground them to a reasonable size.

Next, I welded bungs, I believe from Lucky Devil, into the bottom of the tanks and used the Bung King’s rubber mount kits with straps and rubbers to attach it to the frame. In a sense, this was overkill, but I've experienced leaky tanks and poorly mounted tanks on my way to Sturgis a couple of times. One time, Randy Aaron from Cycle Visions saved my ass and my tank paint job. Later on, Paul Yaffe replaced my piece-of-shit Blue Flame tank with a properly rubber mounted Independent tank. So, goddamnit, this needs to be right the first time. I ran rubber mounts front and rear.

There's a trick to this operation. You need the rubbers in place to make proper measurements, cuts and tack welds. Ah but, too much heat will destroy your rubbers and sink the process. I've done it during mad welding spurts. This time I kept my Bonneville salt sprayer handy, so I could tack near the rubber insert and cool the strap before I damaged the insert. I removed the inserts before final welds.

With the tanks securely mounted, I was confident, except for one aspect: capacity and turning radius. I needed to pull the bike away from the lift clamp and flop the Paughco taper-leg springer from side to side. As I suspected, it was going to hit the tanks. Over the next couple of weeks, I will operate again, slicing the tanks for turning.

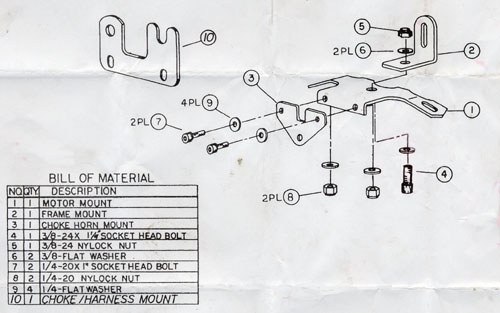

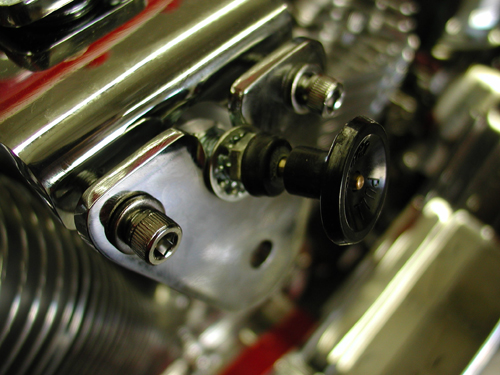

I shifted to making a top motor mount, which worked out like a champ. I made a strap from one Crazy Horse head to the other, then discovered a couple of tabs that would give me the strength and position I needed to hook up with the frame. Top motor mounts are also tricky. They need to be flexible and somewhat adjustable. I made sure the engine was positioned correctly with my BDL primary backing plate, but you never know if something might shift slightly during final assembly, and the top motor mount must be flexible and iron strong.

Without too much fanfare, I attached a piece of modified angle iron to the right side of the motor mount for a coil hanger. I angled it slightly so the spark plug wires wouldn’t bang or rub against the tank.

It just happened that I'm building a railing for my mom's house. She's getting feeble, in her old age and needed some additional support. That meant a trip to the local steel supply house, where I stumbled onto some small chunks of angle iron. I didn't like my original number 5 transmission mount, so I decided to remanufacture it with a heftier piece of angle iron that also reached the frame without a problem. It also allowed me a tad more positioning flexibility for the master cylinder and pedal adjustment.

In the next segment, I'll run the progression of Dick Allen illustrations, so you can see the progress. It's as if I'm building the motorcycle, while Dick and Chris Kallas develop the visual story.

I don't know about you, but these illustrations give me hope and inspiration throughout the build process. Next, I will modify the tanks once more for enhanced Paughco Springer turning radius, then we'll mount the Phil's Speed shop ignition and wiring system to a plate I'll make that will bolt to the top of the tanks behind the gas caps.

Also mounted to same plate of steel will be a manual, vintage Sportster replacement, Bikers Choice speedo driven off the rear Black Bike wheel. Hopefully, the wheels will roll in, I'll find some 23-inch tubes and Larry Settle will mount and balance the Avon tires. I'll set up the wheels in the frame and springer, and then haul the bike to Chica in Huntington Beach. He's going to help me with fender design and mounting. In the meantime, I'll watch the inauguration unfold and stay away from tequila. There's more coming, though. I'm going to modify the trans with a 5-1 Baker drum, and build a set of exhaust with D&D bends and pieces. Hang on for the next installment.

5-Ball Factory Racer Build for 2009-2

By Robin Technologies |

Moving right along, I overcame the Wilmington Mung and slipped back into the shop. It’s like self-induced Christmas for the homebuilder each week when UPS arrives or I score something at the bike swap meet. Ya plan, save small bags of gold and reach out to vendors to make deals, then wait.

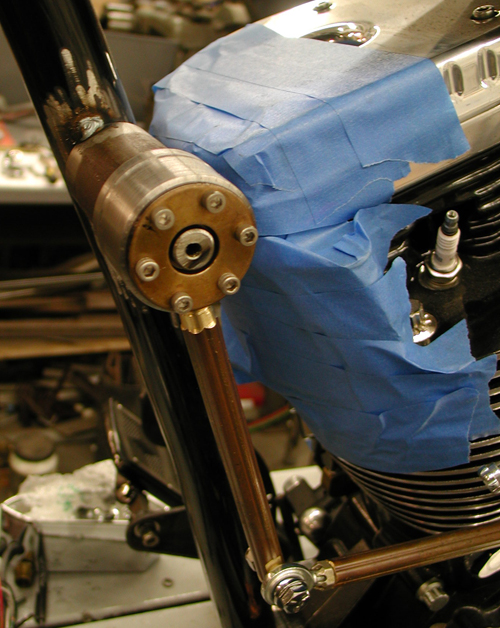

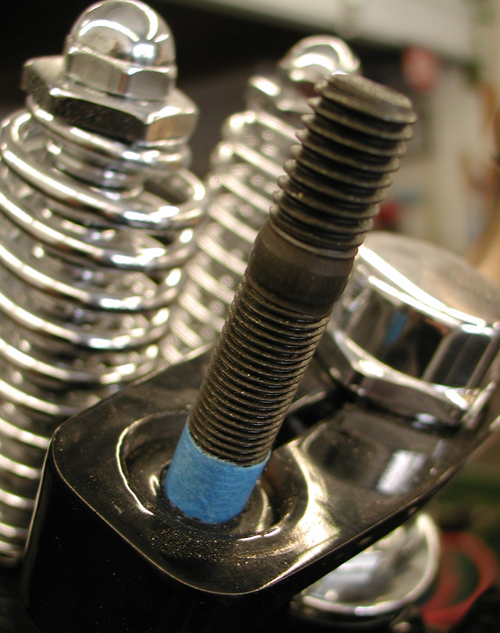

I got all pumped when the bronze risers drifted in from DPPB in Europe, and I immediately tackled the mounting and handlebars. I hit two hardware stores looking for the proper length hardened studs and the second score was doubtful, but I rolled the dice and bought them anyway. As it turned out, 3-inch ½-inch studs with coarse threads on one end and fine on the other worked perfectly.

I tested the fitment by wrapping masking tape around the fine end 3/8-inch up from the bottom. I screwed them into the narrow Paughco leg, and then installed the riser components to see if I had enough length to reach the top bronze nut. I had plenty of threads, so I move the tape to 5/8 inches of securing fine threads and installed all the components. It all fit like a dream.

Then I went to work searching the shop for a set of bars that would give me the look and be reasonably comfortable. I’m shooting for that 5-Ball Factory Racer look, but a bike comfortable enough to ride to Sturgis. That’s always the acid test, and the road-test adventure. I found a set of sorta TT 1-inch bars sans the dimples, since I was going to turn them upside down. I mounted them to the risers, and then determined that I could cut almost three inches out of the center.

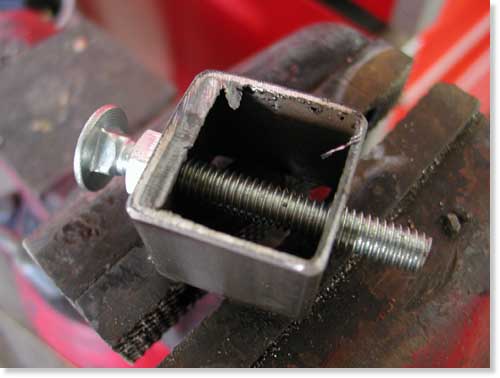

I searched the shop for a chunk of mild steel rod that would make the perfect alignment, strengthening slug for the bars. I removed the burrs from the split tubing and marked the slug center. I tapped it into place, strapped the bars down, so they were perfectly aligned, and MIG-welded them. Just having the bars and risers in place was a rush.

I finally muscled enough cash to have all my welding tanks filled. I took the opportunity to have one tank filled with pure Argon for welding stainless or aluminum. I’ve never welded aluminum, so I broke out my welding book and read the appropriate chapter. I needed twice the gas pressure and almost twice the rod speed and power.

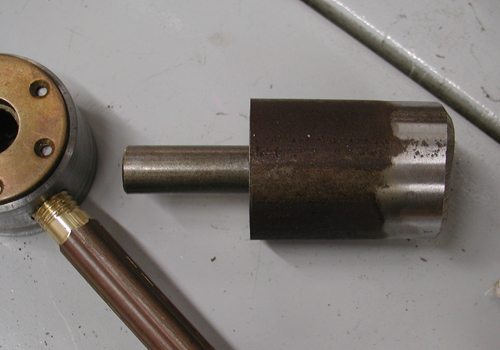

Let me back up for a second. The project was mounting the Crime Scene Rapide headlight. It was a bolt-on procedure, except for the simple aluminum-mounting bung. Once in place, it was impossible to remove the headlight-mounting fastener. I reviewed my options. The fastener would actually touch the top Paughco springs. I looked for an option and found one, but it required welding the existing square bung to the fine-threaded round spacer. I tapped the spacer for clean threads, and then proceeded to weld the two together.

This was a trick. Aluminum must be extremely clean before welding. And since this piece was very small, it could heat up and melt like butter before one pass was completed. I also had some problems with the welder. Since aluminum heats and expands faster that steel, I needed to bore out the tip or run a larger welding tip. The tips come in various sizes, and natch, I didn’t have a slightly larger tip. So Jeremiah grabbed a micrometer and all my tiny drill bits, and started to study the sizes and attempted to drill the tips out. Interesting procedure. We broke bits and jammed them into the bronze MIG welding tips. Finally we succeeded in boring out a tip and the welding moved along.

Then I took to grinding, filing, and rewelding until this headlight bracket was completed. Not bad. I need Jeremiah, the master shaper, to return and give it his final touch.

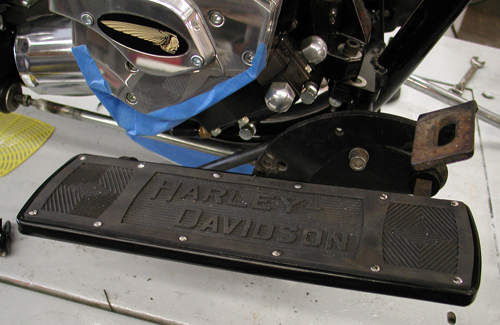

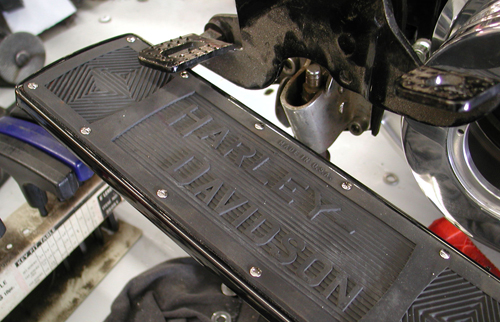

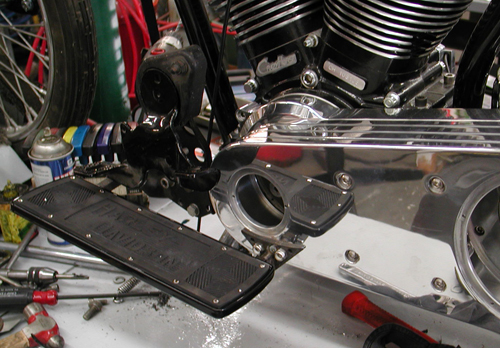

Next, I had a plan to use as many vintage H-D parts as possible. I snatched a stock 1936-1957 mechanical brake pedal and mounting plate, which also acted as the front peg or footboard mount. Paughco already made a bracket that bolts under the front motor mount. It makes the stock mounting bosses available for these components.

This effort placed me eyeball-to-eyeball with a couple of challenges. I needed to make the old mechanical brake pedal operate a hidden hydraulic master cylinder and somehow I had to create a mounting bracket for the rear of the footboard.

There was one more element rearing its ugly head at this point, but yet we turned it into an opportunity. There was no fifth stud mounting plate on the frame, so I started to tinker with a chunk of angle iron. Then I discovered a complete ’98 Dyna rear brake set-up with linkage and the master cylinder. Suddenly, lots of answers were available using the fifth stud-mounting placement.

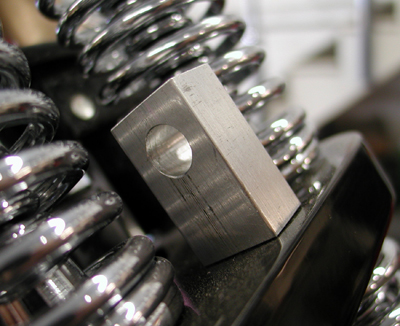

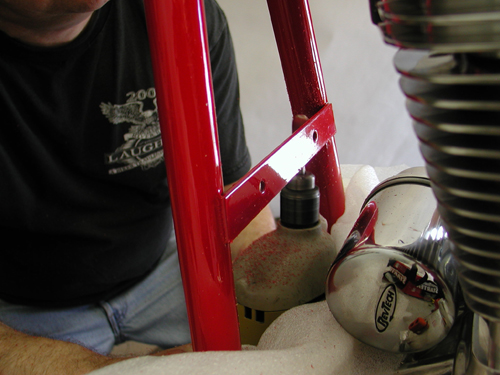

I had to stop dead in my tracks right there. I needed to make sure the transmission was aligned properly for the whole system to work. The brown Santa arrived with a new BDL Softail, 2-inch enclosed belt drive system I’d ordered just a couple of days ago. I pulled out the inner primary, loosened all the mounting bolts for the engine and trans and started my historic alignment procedure. First, I bolted down the rear of the engine and looked for any gaps at the front motor mount. It had a .020 gap. I found a shim and slipped it into place.

Next, I attached the BDL inner primary and pulled the JIMS tranny into alignment with the Crazy Horse V-Plus engine. Then I started on the fifth tranny stud-mounting bracket. I planned to run a kicker, and since this power plant is 100 inches strong, the additional mounting element will strengthen the entire driveline.

No, this system didn’t fall into place. I had oil lines to contend with and the brake pedal and master cylinder didn’t align. At first, I had a grand plan to bend the linkage rod into a jog-over to reach the tab I had welded onto the brake pedal pivot tube. That would have created more problems, specifically with the rear footboard mounting. I needed to straighten it out and machine a 2-inch offset link from the pedal over, which kept the entire system in alignment. The critical aspect will be my tab welding. There will be considerable strain on that puppy, but I think it will work.

Then I ran a ½-inch rod off the top of the pedal bracket and machined a spacer that would catch an original classic footboard-mounting arm. I’m trying to tack-weld everything so I can make final adjustments or catch mistakes before it’s too late. I like welding and sometimes can’t stop myself. I tack my handiwork, step back, eyeball it, check it twice and weld the shit outta it. The next morning I discover something I forgot and I’m fucked.

Since I was into footboards, I moved onto the left one. With the help of Sin Wu on her knees, we checked the angle of my 2003 Road King footboards and attempted to match that angle on the 5-Ball Factory Racer. Again, I used a stock mounting plate with foot clutch pedals. I’m going to make the racer a tank shift, so I bolted up the mounting plate and a vintage kicker arm and bracket, but I needed to drill and tap the Paughco bracket for the lower left 5/16 kickstand mount.

I tried to handle a few moves at once and failed. I broke off the tape in the kickstand mounting hole and I’m still pondering my options. I shifted back to floorboard mounting. I was burnin’ daylight trying to remove the tap. I mounted the front of the footboard and snugged it down at the Sin Wu estimated floorboard angle, then pondered how to mount the rear to the BDL outer primary.

I had to insert the BDL mounting studs into the inner primary with red Loctite first, then the aluminum stud arms, and finally the cool, clean outer primary cover. This turned out to be a breeze. I took a vintage footboard mount, cut it off, and welded it to a Bandit-made bracket. It had to carry my weight, so I added a strengthening gusset to the bottom and believed I was good to go.

In the next segment, we will start to tackle the shift linkage system. Duane Ballard’s wife, Lisa, a contributor for the Cycle Source magazine, delivered this vintage tractor seat assembly for us to test and you’ll see our wacky test next issue. We might also start to tackle mounting the Paughco/U.S. Choppers tanks, Phil’s Shop wiring system and the Biker’s Choice Speedometer, which we hope to mount in the tradition of rear-wheel driven speedometers of the ’20s.

It’s all headed your way in the next couple of weeks.

Goliath CCI Bike Kit Build

By Robin Technologies |

It was hard to imagine, when we stood in front of the garage doors, starring at a pile of boxes, that somewhere in there, somehow, a custom bike lurked. As it developed, except for a non-existent nut or bolt, the CCI Goliath kit was complete. The chromed quandary, could a novice builder, an average American rider (in this case a bumbling college art professor with limited mechanical experience), Ladd Terry, build a hard running 100-inch custom in a week to ten days?

Not just any cruiser, because the components that make up this rolling mechanical architecture scream “modified custom.” It starts with a solid foundation, including the potent RevTech 100-cubic-inch engine, a six-speed overdrive transmission and a Santee 230/250 frame made from 1-1/8-inch tubing. The engine has a two-year/20,000-mile warranty, and the gearbox is covered for 5 years or 50,000 miles. There’s another side to this powder-coated and pearlescent picture. The sheer enjoyment of being able to build your own bike. “It couldn’t be more educational and rewarding,” Ladd said listening to the sharp exhaust crack against the Bikernet.com Headquarters concrete. “What a blast.”

Other components are also top-notch. The 18-inch rear wheel measures a full 8.5-inch wide and is made from solid billet. An 11-inch-wide steel rear fender with streamlined struts covers the Avon 250 rear tire. Billet RevTech brakes grace both ends with clear-coated stainless braided brake lines. Tall 8-inch Custom Cycle Engineering risers securely hold powder coated TT bars that sit atop the smooth billet triple trees, holding 41mm front tubes. A billet dash housing a VDO speedometer adorns the six-gallon Fat Bob tank. The hand controls are CCI chromed, the foot controls are chromed billet. The chain primary drive was enclosed for quiet and smooth operation. Gleaming chrome hangs everywhere. And the complete electrical system includes a high-torque starter and 32-amp charging.

“It ain’t all about parts,” Ladd added, “It’s the experience, the rush of being able to build a tough performance cycle, and I need to congratulate the CCI crew for their organizational capabilities. I couldn’t have completed the task without them or the Tim Remus book on building kit bikes.”

“Hold on,” Ladd snapped as George Hayward, the benefactor for this Beach Ride Charity effort, dropped the clutch to peel out of the garage, “I want to add something.” A college professor always requests the final dissertation. “Even though this was a kit that could be followed to the letter, it allows the builders creative avenues to pursue.” We did, ultimately, build a one of a kind custom with the paint work, exchanging bars and risers, modifying the exhaust and fender rails, changing the pulley and additional small touches to make this ride an American Rider’s creation.

Not bad for a tight team with hand tools and the desire to build a unique machine for a children’s charity, the Exceptional Children’s Foundation in Los Angeles.

Amazing Shrunken FXR 12: Tools And Linkage

By Robin Technologies |

The stock tranny linkage cut to work as our brake linkage.

A week ago I worked on the brake controls with some success. After fabricating a mastercylinder bracket and actually drilling the holes in the proper location, it wouldn’t work. I needed to turn the master cylinder upside down. I called Frank Kaisler to confirm that it was a remote possibility, it was. I cut another chunk of steel plate, drilled the holes again and dug through drawers to find a pushrod. Nothing.

Parts and pieces we used to cobble together brake linkage.

The master cylinder in place upside down under the tranny.

The stock stainless shift rod cut for a master cylinder pushrod.

I used a stainless steel shift rod unit for lots of adjustment, but had to grind/taper the end to fit. I also used the transmission shift lever for the connection. I cut Giggie’s brake axle to length and sliced the tranny shift linkage. Then I welded the linkage to the axle. That was a mistake. I should have machined the pieces to fit together, but it will work. The other end of the linkage was the perfect mate for the shift rod I cut and fashioned for the handmade master cylinder push rod. I lucked out. I think it’s cool.

The inlet oil fitting had to be moved to make room for the brake linkage.

Here’s the tranny-gone-brake linkage welded to the brake axle.

That was last weeks endeavor. This week I stumbled. It all began with a set of exhaust I fabricated, from bits and pieces of other exhaust, for the Amazing Shrunken FXR. They worked out all right until my humble associate, Nuttboy, was assigned to grind the welds. Ya see, I held one piece of pipe against another and tacked them. The mating surfaces were not aligned perfectly, so when Nuttboy unleashed the Makita grinder to round off the welds he cut right through the pipes forming cavern-like gaps.

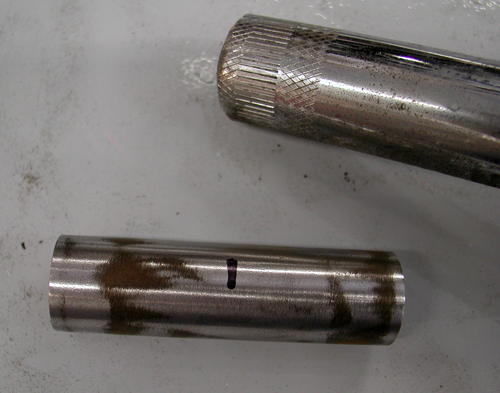

Kustom fab uses pipe inserts to hold pipes aligned securely for welding.

I had to enlarge the slot to make the insert fit.

The insert won’t slip into place with burrs in the pipes. I had to grind them clean.

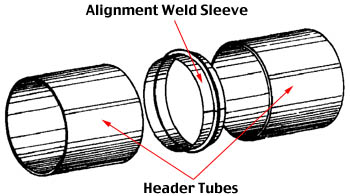

Lots of builders in the industry make their own one-off custom exhaust, so I started asking around about tools. Most don’t have tube benders, so they follow the same strict regime I did. They piece exhaust systems together using bits and chunks of other systems. One company will ship you a kit of various bends to work with. I inquired as to how shops held two chunks of tubing together in order to MIG, TIG or even gas weld pipes. The information highway opened up to me. Roger from Kustom Fab in highway takes a 1-inch section of like pipe, slices it (so the O.D. shrinks) and shoves it in one section of pipe then in the other. Simple system that adds strength but reduces the I.D.

Here’s the insert in place. It works well and adds strength but will restrict exhaust flow.

This system also makes welding easy.

Some of the junk I dug up to kick-off my pipe clamp tool experiment.

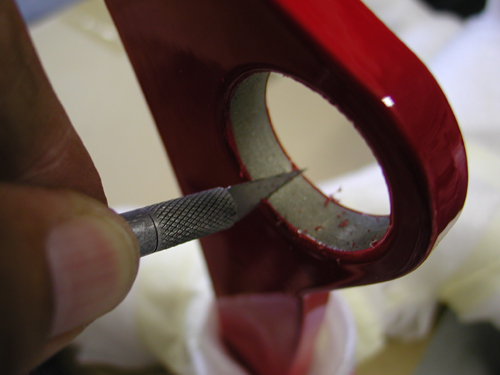

Another builder told me of a C-Clamp arrangement using angle iron to lock chunks of pipe in-line. Scott from Chica’s explained a small unique tool that pulls the segments of pipe together using feeler gauge thin material. After tack welding the pipe segment, the clamp is loosened and the feeler gauge material slips out. Irish Rich pointed out that large hose clamps and chunks of angle iron work fine to hold pipes for tacking.

This was my bullshit attempt at building this tool.

I brazed the feeler gauge to a nail and the nail to the end of the bolt.

Here’s the completed tool. It looks better than it works.

This shows the clamp in place. In order for it to work properly a notch needs to be ground in the pipe for the nail shaft, which is thicker than the feeler gauge.

The guys at Chica’s also told me about a wide stainless hose clamp with slots or holes that can be used to hold two tubes together during the tacking stage.

I found this puppy at Home Depot and thought I had hit gold.

I drilled the stainless strap with a small drill then 1/2-inch for tacking room.

Then Fab Kevin clued me into Holley, the hot rod car part builder, who makes a sleeve that holds two pipes in alignment for tacking. I looked them up on the Internet.

Our “Alignment Weld Sleeve” allows the fabricator to align, hold and weld two pieces of mild steel tube without help. Because no rod is needed, the welder has a free hand. The “Alignment Sleeve” assures a perfectly aligned joint with no weld slag inside to reduce the tube diameter and restrict air flow. Perfect alignment and just the right amount of welding material results in a very professional looking weld. Weld Sleeves are packaged 20 sleeves per bag.

See, I couldn’t find a hose clamp to do the job. I need another hardware store run.

This is where the story runs astray. I followed each veteran’s suggestion and began to fabricated every exhaust pipe alignment device known to man. I cut, brazed, hit Home Depot, bought clamps, hoses, sliced my only .013-inch feeler gauge, dug through drawers and took photos along the way. No shit, I fucked up every tool design suggested.

This is how it’s supposed to work. Unfortunately the clamp I bought was too large.

I didn’t have two hose clamps that would pull the angle iron hard against the tubing. The wide stainless clamp notion was golden, but I bought the wrong size at Home Depot. The feeler gauge routine was followed to the finish, but my tool doesn’t work without a notch snipped in the pipe. The C-clamp notion is too involved for my thinking so I decided to buy two clamps and modify them. Of course I didn’t have two spares to screw with. And finally the perfect solution from Holley was unavailable from my local auto parts store. I’m forced to buy their catalog.

This is the C-clamp notion. I’ll build it after I hit Home Depot again.

If tonight you called and offered me a cool million to build an exhaust system, I still don’t have the tools. I need to hit Home Depot again. I almost fired myself last night, but you get the idea.

–Bandit

Custom Chrome Goliath Kit

By Robin Technologies |

This shows just a fragment of all the parts involved.

Hang on. Here comes a complete build of a custom CCI Goliath Bike Kit. We built this 100-inch Rev Tech monster in nine days. The bike was assembled to promote the Annual Beach Ride, at the Queen Mary in Long Beach, through the efforts of Custom Chrome, George Hayward and Bikernet.com. We assembled the bike in the Bikernet Headquarters for the children’s charity ride. It was also featured in three issues of American Rider, but this is the extended, unedited version with charts. Before we get started, I want to add an editorial note. If you read this and want to add something, don’t hesitate. We can change the text whenever we goddamn want. If we missed something, you have a special tool, a correction or want to point out what a bunch of baboons we are, don’t stop, send a Your Shot. Let’s hit it.

“What the hell,” Nuttboy mumble, “what did you volunteer me for?” He scratched his butt, with a 9/16 open end wrench, as we loaded box after box of components into the garage. If CCI could somehow ship the components without the retail packaging, they would save a fortune. We had a truck load of plastic peanuts, plastic bags and cardboard.

The Goliath is a complete 100 inch, Rev Tech powered Softail kit. It comes with every nut and bolt. “And a few extras,” Nuttboy chimed in distractedly. Also included was a Softail manual and a Softail Parts book. We also referred to the Tim Remus book, “How To Build A Kit Bike”, from Wolfgang Publications.

“The Remus book was the most help, but there were big gaps in information,” Nuttboy grumbled. “We often had to scan the photos in the book in a fleeting effort to figure out a procedure that wasn’t described.” Maybe this series of articles will help.

The entire bike was built in a garage using normal hand tools. A professional shop came in handy on only two occasions: Pressing the clutch together, tire/wheel assembly and balancing.

The frame, wheel rims, and miscellaneous parts were powder coated by Custom Powder Coating in Dallas (214) 638-6416 to match the hue used by Santini Paint (714) 891-8895, for the sheet metal.

Here’s the massive rear wheel. It was powder coated red on the rim, then clear powdered. Finally George, the Wild Brush, finished the edge with a wide stripe.

“Violent Red I’d call it,” wise-cracked Nuttboy, “it looks hot enough to fry your bratwurst.”

We made sure the tank was pressure tested and sealed at the painter’s. We organized the parts as best we could and once the powder coating was returned Nuttboy shaved off the paint and tape where the motor mounts and tranny mounts were located. Dallas handles frames for American Iron Horse, so they know what to mask, which saved time. Nuttboy started checking the surface around the neck and beating the cups into place with a brass hammer and a massive punch. They must be pressed in completely.

We tried to organize the parts. This was the electrical stack.

We cleaned the area around the cup area on the neck to make absolutely sure the cups would seat entirely. That’s critical. If the cup seats more while vibrating down the road the front end will loosen and add to crucial elements that could lead to a high speed wobble.

We used a 20-year-old Bikernet punch to drive the cups home. Make sure they’re aligned properly.

You can tell by the changing tapping sound that the cup is fully in place.