Mudflap Girl Part 2, the Bandit Engine and Spitfire update

By Robin Technologies |

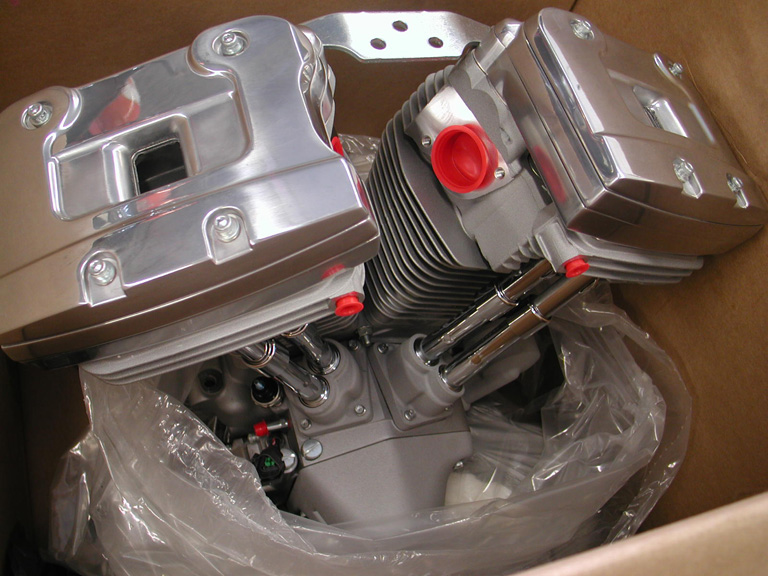

As it turns out, the factory hired the S&S crew to assemble their Evo line of engines. What a natural. I liked that notion all the way around the block. First, it means more American hands in my new engine. Plus, what could be better than to have the best performance engine company on the planet working with the factory on the last and most refined V-twin configuration?

For this crew, and lots of riders all over the world, the FXR Evo is the best of the best. So, for Bikernet, this became the year of the FXR and the Evo engine. I asked the factory about their Evo engine program and received the following information.

A Modicum of Harley Engine History

The first 74 cubic-inch V-Twin engine on the JD and FD models was introduced in 1921 and the 45 cubic-inch side-valve V-twin engine (later to be known as the Flathead) on the D model debuted in 1929. The Flathead engine proved so reliable that variations of it were available on Harley-Davidson motorcycles as late as 1973 (servi-car trikes).

In 1936, Harley-Davidson introduced the EL model with an overhead valve, 61-cubic-inch engine. With increased horsepower and bold styling changes, the motorcycle earned the Knucklehead nickname, due to the shape of its rocker boxes.

New features were added to the 61 and 74 overhead valve engines in 1948, including aluminum heads and hydraulic valve lifters. New one-piece, chrome-plated rocker box covers shaped like cake pans earned this engine the nickname Panhead. The engine introduced on the Electra Glide models in 1966 to replace the Panhead became known as the Shovelhead, again due to the shape of its rocker covers.

1340CC Evolution Softail Engine – Silver and Polished SPECS

Type: 4-cycle, 45 degree V-twin

Bore X Stroke: 3.498 X 4.250

Displacement: 80 cubic inches or 1340 cc

Compression: 8.5:1

Torque ratings at 3,500 rpms: Touring with fuel injection, 83 ft./lb.

Touring w/carb 77 ft./lb. @ 4000 rpm

Dyna/Softail 79/76 ft./lb.

Miles per gallon: 50 hwy/ 43 city with a touring model using a carb

55 hwy/ 43 city Dyna or Softail

Variety and sales info:

1340CC Evolution Softail Engine – Silver and Polished

Since the first single-cylinder built in 1903, engines have been the heart and soul of Harley-Davidson history. Each motor has made its unique contribution, and the V2 Evolution engine is no exception. With the Smart Start Engine Program, buying a new Evolution engine has never been easier. When replacing your Evolution motor, Smart Start offers brand-new, factory-tested engines at an unbeatable price. Choose the standard silver and polished Evolution, sinister black, the classic black and chrome or the silver and chrome finish. Either way, you won’t just be making a new start; you’ll be making a smart start.

16161-99

IN-STORE PURCHASE ONLY, Contact dealer for pricing and availability.

Fits all ’99 Softail models. Does not include carburetor, manifold or timer cover.

MSRP US $3,295.00

1340CC Evolution Softail Engine – Black and Chrome

16160-99

IN-STORE PURCHASE ONLY, Contact dealer for pricing and availability.

Fits all ’99 Softail models. Does not include carburetor, manifold or timer cover.

MSRP US $3,995.00

1340CC Evolution Softail Engine – Silver and Chrome

16177-99

IN-STORE PURCHASE ONLY, Contact dealer for pricing and availability.

Fits all ’99 Softail models. Does not include carburetor, manifold or timer cover.

MSRP US $3,495.00

When my engine arrived, I immediately hauled it in the Bikernet Hearse to Bennett’s Performance for a slight performance upgrade. I needed to let that puppy breath without messing with the reliability aspect. Sharing the same building on the edge of Signal Hill, California is the headquarters for Branch O’Keefe. John O’Keefe worked for Jerry Branch for decades and ultimately bought the business when Jerry Branch decided to retire.

We’re looking at several options for stock engines and for rebuilds. We have three touring models coming together right now, and they are all 80-inchers. One for my son, my factory motor, and Dr. Hamsters 200,000-mile Evo rebuild by Bennett’s.

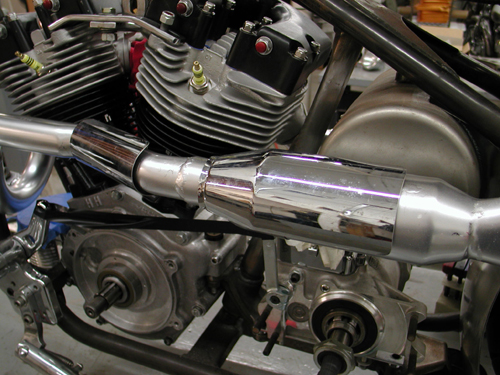

I’m running the brand-new factory plain Evo engine with the Andrews EV-27 cam and Andrews chrome-moly adjustable pushrods for less flex, a new cam bearing and the Branch flowed stock heads, for 8.9:1 compression, 78 cc Branch-flowed chambers, and 75-80 horses at 2,600 rpms.

The next higher upgrade step from Branch is the EV-51 cam and additional headwork and shaved heads for a 10:1 compression and 85 horses at the same rpms. And finally, a customer can run with an EV-59 Andrews cam and 10.5:1 compression and 90-95 horses. Not bad for never taking the barrels off.

“I like rpms,” John O’Keefe said, “and the new ignitions allow these engines to burn more fuel and bring out the horses.”

The key to all this performance is the headwork set to match the cam, and John O’Keefe has studied this science for most of his life. The key is building a mid-range hot rod without sacrificing reliability.

The first move was to strip the engine and deliver my fresh factory heads to the Branch team. Eric Bennett set my beautiful, plain H-D Evo engine on his clean room bench and removed the top motormount, the top rocker box that came off with the middle ring. We noticed much improved, one-piece factory Teflon gaskets. We won’t mess with them. Then Eric removed the rockers, the pushrods, pushrod tubes and rocker boxes. We also retrieved the new base gaskets to reuse.

Then he removed the head bolts, the front head, and the rear head. I had already purchased the Andrews EV-27 cam from Branch O’Keefe, and Eric and I started to prepare for installation. He removed the point cover, ignition, and cam sensor.

He had a terrific Trock tool for removing the cone cover. It’s always a bastard to try to carve around the narrow gasket surface with a screwdriver or a knife, hoping to find opening and risk damage to the cases or create a leak by scratching the gasket surface.

“We always replace the new factory cam bearing,” Eric said, “with a full compliment Torrington bearing. The factory ran the good ones from ’55 to ’92, then they shifted to a cheapo brand. It’s also not a bad idea to replace the factory plastic breather gear with a solid JIMS unit.”

I scrambled to take notes and photographs while Eric peeled into my engine. He popped a factory set of magnetic tools into the lifter stools to hold the lifters up during cam removal. I wish I had a set of those puppies.

“It’s interesting,” Eric said. “Virtually every stock cam is .060 longer than any aftermarket cam.”

Eric pre-measures the cams and adjusts the thrust washers before replacing the cam, which you will see in the next report, when we study the Branch recipe for performance, the headwork, and modifications. He replaces the valve seats for larger valves, then ports and polished the chambers. You won’t believe the long-lasting components Branch uses.

Then we will watch Eric replace the stock cam with the Andrews unit and adjustable pushrods, and put the whole Evo puppy back together. “Don’t forget to order a top end gasket set,” Eric reminded me as the rain cut loose outside and I wondered if this winter season would ever end. I need a ride.

Then Eric grabbed a JIMS tool and a couple of wrenches and in 30 seconds pulled the cheap cam bearing from the new cases.

“I’ve seen these go south in 10,000 miles,” Eric said. “I’ll never understand why they replaced a perfectly good quality bearing with this junk.”

Just as quickly Eric took an aluminum guide and a mallet and tapped the new bearing in place, another 10 seconds passed, and we were finished.

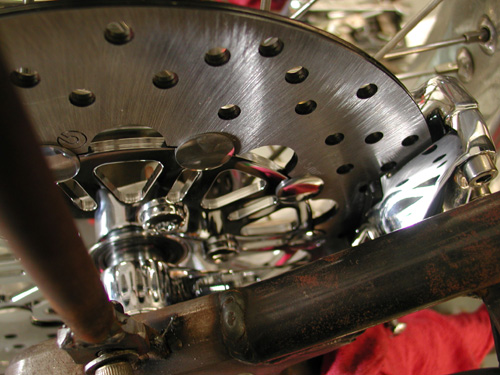

A couple of days passed and I thought, just maybe my frames and front ends would be completed at Spitfire. On a hunch, I peeled 57 miles away from the coast in the hearse while listening to KJazz on the radio.

It was quiet as I wandered into the vast machine shop, welding shop, bike assembly area and ran into Joe Cavallo, Paul’s dad, who was hunting around the shop for Softail brake anchor brackets. He greeted me and said something about shop organization. The Spitfire and American Made business model has faced serious transformations over the last couple of years.

As I mentioned before, Paul was the partner and manufacturing arm of Hellbound Steel motorcycles. American Made manufactured fast moving products for a bunch of now defunct companies such as WCC. At one time, they were building hundreds of choppers each month, and thousands of products in a much larger facility. During the last year, they adjusted their business model and tightened their facility. They rewired their building, replumbed it with compressed air lines, and kept building products.

It’s tough to stop everything and regroup, scour through boxes of tools, base material, parts, and junk. With a skeleton crew they are still building any frame a customer needs, including big twins, rigid Sporty frames, British custom frames, and even frames for Yamaha 650s and Honda fours. They also build an entire line of forward controls, gas tanks, handlebars, girders, and glide front ends (bowling pin), pegs, oil tanks (a variety of styles), trees and taillights. Paul is the mad scientist of the group. As a kid, he manufactured exotic gun cases.

He’s the kind of guy who will catch a notion in a cup of Starbucks coffee, in the morning and by the evening, he has a new product. It’s not a one-off either. It’s fully designed and configured for multi-manufacturing.

Some of his crew have been working with Paul and his dad for decades, including Larry, who is their master motorcycle assembly guru. He knows it all. “Pull the alternator rotor off that engine before you run it,” Larry told me. “Check the wires for twists or tears.”

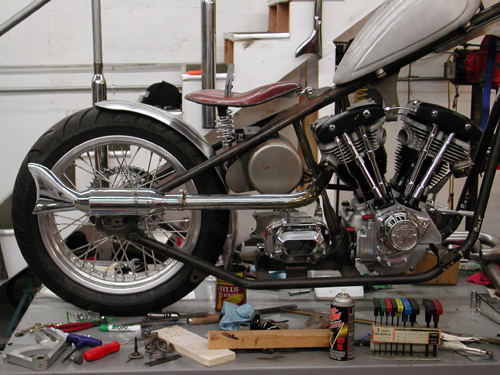

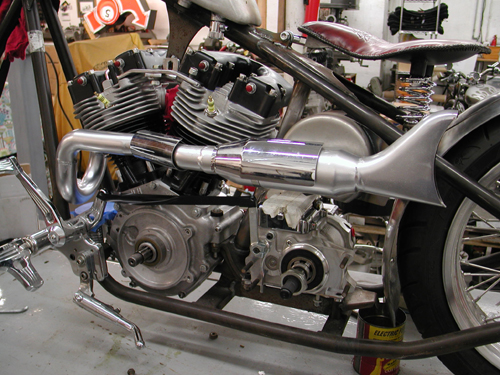

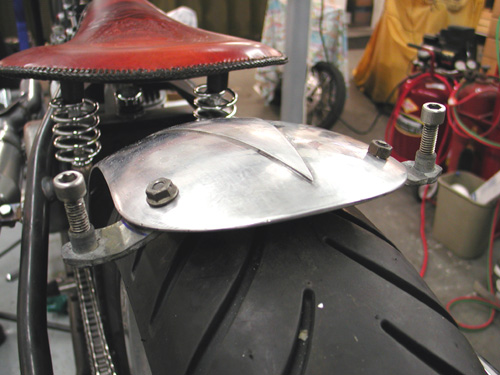

I made a note. Then we made our way into the frame jig area to see the FXR frame progress. The FXR fever caught on and there were at least five FXR frames in the making. The first was based on the pro-street configuration with additional gussets, the squished wishbone, for the single-loop notion and 36 degrees of rake for a 2-inch longer girder front end.

They discovered some issues with my request for a V-style frame in keeping with the stock FXR configuration. I also hoped for less rake and a shorter Frisco style girder front end style. Paul was working on my unit with a 30 or 33 degree rake, but he also started building a couple of drop seat FXR frames, including one for himself.

We are also going to try a slightly longer swingarm suggested to us by Dar, the boss of Brass Balls for his FXR configuration. He wanted to pull the rear tire out of the frame some, and I was willing to try it. They are hot after these frames, since Paul plans to ride one on the Diablo run that kicks off on May 5th in Temecula, California and rolls toward the border. Don’t know if we will make it.

The plan for now is to pick up the frames, swingarms, axles, and Spitfire girders, on Friday April 8th. Between now and then, hopefully we will wrap up the engine and bring that puppy home to the headquarters. We are trying to match up these Mudflap Girl FXRs wherever possible, but not always. We are going to run long and short dogbone risers from Custom Cycle Engineering, but we’ve ordered a new set of Raw 2-into-1 performance pipes from Bub for Frank’s FXR, and I’m running a D&D 2-into-1 system. I’m running a Frisco’d and stretched tank and he’s running something completely different. He’s running a Klockwerks rear fender and I’m running something bobbed. I’m getting seriously ahead of myself. See you in a couple of weeks with the next report.

–Bandit

Sources:

Bennett’s Performance

Branch O’Keefe

JIMS

Spitfire

Custom Cycle Engineering

D&D

Bubs

Harley-Davidson

Rivera Primo Inc.

Belt Drive Unlimited

Metal Sport Wheels

Sturgis Shovel Part 11

By Robin Technologies |

I’m not sure if I’m keeping everything in line. But this segment took us to Foremost Powder Coating in Gardena California. I was at that point when these shots were taken. I’ve had a Powder Coating Sponsor for years, Custom Powder Coating in Dallas. They’re good people and know how to handle custom work. They’ve handled jobs for Strokers Dallas, our custom for American Rider and even the 1928 Shovelhead for Bikernet.com.

Powder coating costs have dropped and it doesn’t make sense to ship a frame to Dallas. It would cost less to have it Powdered in LA than to pay for the shipping. So I looked around the area and was recommended to Foremost Powder Coating (877) We-Coat-it, 1608 W. 139th, Gardena, CA 90249. These people have their shit together and the girl who runs day-to-day operations, Esmeralda, is a delight on the eyes and to work with.

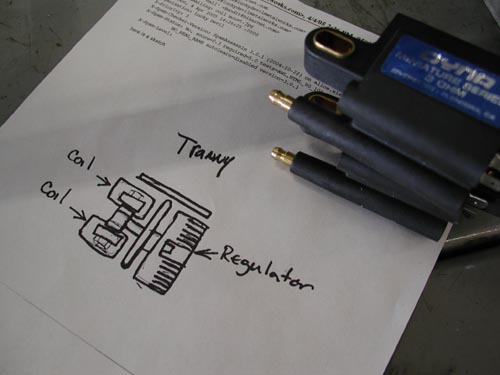

Let’s back up, though. Just before teardown for Powder I needed to think electrics. Kent from Lucky Devil Metal Works in Houston sent the above illustration for mounting the Compu-Fire voltage regulator under the tranny with the small Dyna Coils from Custom Chrome. I pondered that drawing and decided that I didn’t like the notion of putting my coils at ground level. What if I ran through a rain puddle? He’s built bikes using this technology several times and so has the guys at WCC, so it must work in most circumstances.

I decided that since I was going to run the Compu-Fire engine based electric starter that I had room under the oil bag for the coils. I still installed the sealed voltage regulator under the tranny on a 3/16 sheet of aluminum. But then welded brackets under the Craft Tech Oil bag to hold the two coils apart.

This was a delicate operation and ultimately the new Accell Sparkplug wires run right across the top of the RevTech Tranny. I also had just enough room behind the coils to house the wiring for the single-fire Compu-Fire ignition system. I thought through most every aspect of this motorcycle right up to the wiring business, then came up with a nuts notion, which I will explain during the final assembly process. It actually worked out fine with a handful of scary moments.

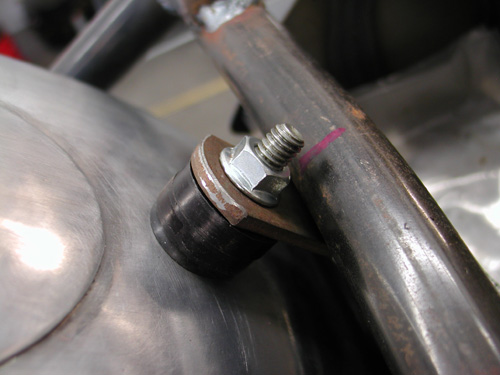

I welded four bungs that housed 3/8 fine threads to the frame with my Miller MIG welder. Ultimately I mounted the Compu-Fire voltage regulator to the pipe side (right) and it worked out fine.

It was time to strip the Engine out of the frame, complete final welds, grind the welds and ship the parts to Foremost Powder. I needed to create a temporary engine stand to hold the S&S 93-inch Shovel in place. I used a RevTech engine stand and mounted it to a junk metal table leg. It worked perfectly and I shoved it in a corner for future use.

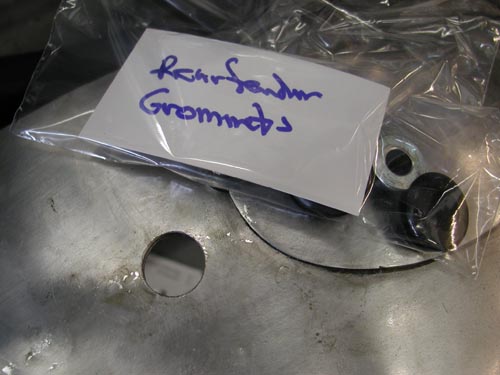

As I tore portions of the bike down I formed zip-lock bags with labels to hold the fasteners. You’d be surprised how fast you forget which spacer fit what, unless you organize. Mike Egan told me years ago that he takes photos of every part and organizes his assembly with photographs to demonstrate how components matched or were fastened. Since I try to take shots constantly I had an archive of various aspects. Hell, I just need to turn on Bikernet and look up the tech.

The next move was to finish welding any tab or bracket that had been tacked or partially welded. MIG welding is a breeze, but not as dead certain as TIG and I’m after a Lincoln TIG welder.

Here’s all the fasteners, grommets and spacers in bags with biz card labels. It works like a champ although I replaced some of these fasteners with stainless Allens wherever possible.

Next I dug out all my tools for grinding welds and went to work. This level takes a great deal of patience and artistic style, which I don’t have. The more time and patience, the better each weld will look. There is actually a process for bondo filling powder now, but it’s more costly. If you don’t want welds to show ask about it. If you don’t mind the look of a clean weld, just powder. I wanted the look of a machine, nothing slick.

There’s one more consideration. Try to make each weld look the same as the next one for consistency. In my case that was tough. Some of my welds were decent, others sucked. I did my best, but my welds didn’t compete with the Paughco paid professional beads.

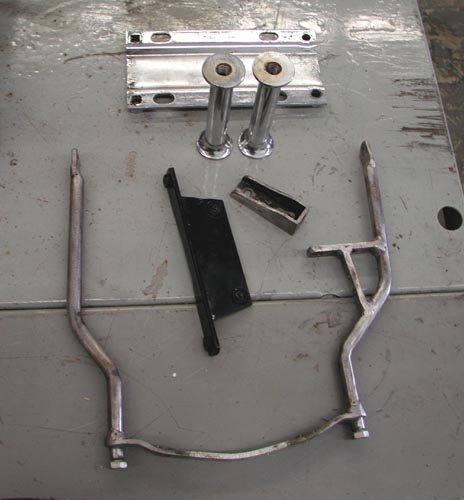

As I finished grinding and drilling holes in the frame for wiring I separated each group of powder finish parts and took a shot for the Powder guys at Foremost. It was a lifesaver to be able to hand them a shot of each group of parts since some had to be sand blasted before the finish was applied.

One more comment on drilling holes for wiring. This was one of the first times I drilled plenty of wiring holes. Remember Frank Kaisler’s rule? Drill the hole. Ream it out on a taper to prevent cutting your wires. Then with emery cones make sure there are no razor-sharp burrs in the tubing. Frank ran the emery paper then he’s twisted a Kleenex and shoved it in the hole. If it caught he’d sand the edges more. If not it was good to go. Let’s hit it to the next chapter, we’re burnin' daylight.

Mudflap Girl Part 1, the Concept

By Robin Technologies |

Life is nuts, or is it just me? Fortunately, we have motorcycles and women to chase. And this year became the year of the Evo, the FXR, and the mudflap girl. I’m scratching the back of my head and wondering how to kick off this build for 2011. There’s a lot on the plate this year and it’s a tad difficult to explain. First, I must fess up. I’m turning 63 this year and no more riding rigids to Sturgis, or even chasing young broads. Ah, but the adventure continues. It’s actually a blessing not to be hassled with women troubles. I’ll let my son, who just turned 37, deal with the addiction to soft curves. I’ll hide out and watch…

The solution for my missing long distance rider was an FXR, and I have one, the John Reed V-Bike that I took to Bonneville in 2006 and set a 141-mph record with a top speed over 150. Unfortunately, I have a hip problem and can’t ride mid-control bikes anymore. I even modified that puppy, but that didn’t do the trick. I love that bike. So, what the fuck was I going to do?

Okay, so I started to piece this bike together. We factory re-manufactured a ’98 Evo engine and JIMS rebuilt the transmission into a six-speed. I had a couple of Renegade Wheels and Progressive Suspension shocks. Then I had a conversation with Kenny Boyce, the man who designed the Pro-street FXR frame. He wasn’t happy with now-defunct Quantum. I also found out that some of these frames break in front of the seat area at the backbone. The project was moving forward with a Custom Chrome, super-wide, upside down front end, Aeromach risers, and we added super wide, Burly bar highbars.

I even had an aluminum mudflap girl oil tank I ordered from Nick at New York Choppers. The bike was leaning toward a pro street touring model with a set of Redneck Softail fiberglass saddlebags and a Klockwerks touring bike rear fender.

I was rolling when Kim Hottinger called and asked if I could haul my old ass out to the American Built/Spitfire manufacturing facility in Rancho Cucamonga, California. Paul Cavallo was the engineer/manufacturing guru behind Hellbound steel. As we watched the production chopper industry dry up, in the wake of a floundering economy, only the diehard survived, and I wanted to support anyone who understood the code of the west.

The brothers who love motorcycles, choppers, bobbers, and custom parts continued to jump up every morning and do what they adore, work on motorcycles. Some went from building hundreds of bikes every month to a handful, but they kept building. Paul downsized and kept rolling with his father at his side. When I saw what he was up to, I was inspired. He can build any frame, for any motorcycle configuration, so my mind went wild. We could build a Frisco’d and stretched, single-loop FXR, and I dragged an old Durfee girder out to his facility so Paul could see how the master built the originals. Imagine an FXR with a state-of-the-art girder.

Paul is a wild man when it comes to building and manufacturing anything. He re-engineered the girder and refined the looks, and added two shock mounts to incorporate a state-of-the-art front suspension. Over the next year, you’re going to witness Paul’s Spitfire abilities with features in several national magazines, and you’ll begin to see his products pop up in Custom Chrome catalogs.

The more we moved forward with this bike, the more inspired I became. This was a bike for me, maybe the bike for my old-guy riding future, now that my Road King was down the road. So I went to Paul with the deal of the century: build two of these frames and front ends. I spoke to Paul, then to my son.

There had to be a goal behind this effort. We would ride to Sturgis together. Shit started to happen fast and I ran into a TV producer who wanted to follow the build, and Leomark studios got involved.

Next, I reached out to Chris Kallas and we started to work up a concept drawing. Here’s some of the e-mail that flew back and forth.

Here’s my initial description:

Frank’s bike: classic black mag wheels from Metalsport. Klock Werks rear dresser fender on Frank’s, might bob it. Both wheels will be mild width. Mudflap girl theme on my bike and Hardball tattoo on Frank’s. Paint reversed from Frank’s bike to mine. Forward controls on my ride, Frank’s will run mid controls. Rubber pegs, grips. dog bone-style tall rubber mount risers. Shotgun pipes. One Redneck bag on the left of Frank’s bike. We also talked about a small front fender.

–Bandit

Some questions?

Black and chrome or silver Evo engine?

Your wheels? Mag or spokes, what kind?

Style/brand of headlight, tail light?

The risers are the type with rubber mount at top?

Carb/aircleaner?

Shot gun pipes, staight, no mufflers?

Style of seat?

Your fender the same not bobbed?

Brakes? Dual or single up front? What brand of rotor/caliper?

If any of these things aren’t specific yet, they could be semi generic on art.

If you can send any photos or links to of fenders, wheels, bags, brakes or controls, it would be helpful.

As for paint, just a thought.

It looks good with lots of black or aluminum, and chrome.

It also looks good with your signature orange accents or striping. Since I’m not crazy for white frames, they could both have blue frames and just flop the two-tone paint on the tanks and fenders.

— CK

Here’s the basic FXR platform showing the frame modifications.

This is with a 3″ extended swing arm.

I need to go back and recheck some measurements but it will give you a

rough idea of the stretch up front.

Is this the type of exhaust setup you were thinking of?

When you said shotgun and 2-into-1, I wasn’t sure.

— Chris K.

I think we should go with this type of exhaust, if we plan to pack passengers. I’m going to ask Dar about that swingarm, but my tendency is to extend it about 1.5 inches, not 3. The stretch looks great. Let’s fuck with those fender rails, arch them, or make them disappear and bob the fender slightly. Plus I think we will need to lower the rear at least an inch, with shorter shocks.

–Bandit

Hey, here’s my first crack at putting it all together. Overall the stance looks good. Since it’s a rough draft without much decoration, I just threw a couple

of mud flap girls on it. I thought I’d try a traditional Sportster/FX headlight with it’s rubber- mounted bulb to stay with the theme of using rubber pegs, grips, and

rubber mounted-risers…. not to mention a rubber-mounted engine, plus I like them.

The frame tube behind the shocks creates a challenge for curved fender struts. I’ve included a couple of photos of some frames so you can check out that area, plus for general interest I tried mounting the tank higher (Frisco style) but thought this looked better.

You might use a semi-later model Sporty tank (when they first started making them larger but still had a carb).

I don’t know at what angle or how Spitfire plans to deal with the secondary neck brace under the tank, so just drew it how I thought it might go.

When you said a Fantasy in Iron tear drop air cleaner I took that to mean a plain Goodson (no rib), for engraving. (We now have a Roger Goldammer air cleaner for Frank’s bike)

Since you need to run a front fender, I made it small. I like when they show most of the top of the tire.

Questions:

Who’s handlebar and foot controls do you plan on using?

How about brake calipers?

–CK

Hey, Chris,

I feel like I want more attitude. How about the tank mounted in line with the bottom of the top bar and stretched a tad at the back to more of a point? Take out the stress bar and add a gusset there with a mudflap girl cut out.

Check the news. I ran a shot of the air cleaner, but you nailed it. Did you check out the heavy green flake and silver bike? I like that theme. My bike will have a plain engine. I thought that style worked well with the plain silver, driveline. And I liked the green springer to match the frame.

We don’t need to go with green. It could be almost anything and silver, then reversed for Franks, with a silver frame, and colored sheet metal.

–Bandit

If the Redneck bags wouldn’t fit, we looked at what Bob T. runs on his fantastic RT.

Part number for bags:

’87-90 FXRS conv bags

H-D 90702-89 left

90703-89

As you can see we are flying at this effort. Don’t miss the frame build in the next segment. As it turns out Frank and I will be running the same drivelines: JIMS six-speed transmissions and Harley-Davidson Evo engines.

Sources:

5-Ball Factory Racer Tuning issues

By Robin Technologies |

This has been the strangest tuning dilemma I’ve ever faced with a motorcycle in my 40 years of messing with these bastards. I fell in love with our Factory Racer CrazyHorse 100-inch engine. The day we started the bike for the first time, it fired to life immediately, no hiccups, stumbles, or coughs. Every time I hit the Phil’s Speed Shop electronic system starter button, it immediately rumbled to life. Then we attempted a break-in ride and it blubbered badly at mid-range. If I nailed it, it jumped forward, then stumbled and nearly died. I was perplexed.

At first we thought, and so did S&S, that our Crime Scene air cleaner, facing backwards, was the evil culprit. We began an extensive investigation. Larry Petri, the master Chop N Grind mechanic, came over and we tried some jetting changes, which didn’t seem to help. We went to Bonneville, so we shifted gears to our Peashooter project until we returned.

While cleaning the shop after Bonneville, I came across another S&S Super E, and installed it immediately. The bike did the same thing, so we ruled out the carb for a minute, and I investigated whether there was any chance it could be the ignition.

According to a few CrazyHorse experts, the Thunderheart ignition system could have been the problem, so I reached out to Thunderheart in Florida. They asked me to send them the ignition module and the cam sensor, which I did. They told me the cam sensor was defective and replaced it. I re-installed it and the bike did the same thing, blubbered at mid-range. I performed another Thunderheart test by running a power lead from the battery directly to the coil. No change. I tried the power lead to the other coil connection, and believe I blew out the ignition. It wouldn’t start again.

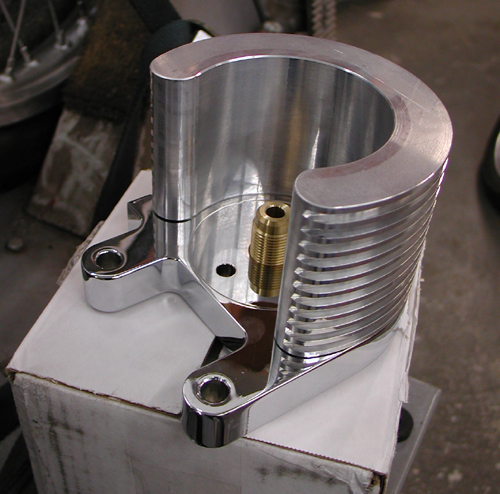

After speaking with several builders, I was convinced the problem was the Thunderheart. Frank at Black Hawk Motorworks builds a billet bottlecap cone, allowing us to install any Evo ignition to a CrazyHorse, so I headed in that direction. Frank recommended a mid-range S&S cam, which would require new adjustable pushrods, also from S&S. Ultimately, I ordered the S&S Quickee pushrods, so I didn’t need to remove the rockers for installation. Life was looking up. I also ordered a single-fire ignition from Compu-Fire, one of the easiest ignitions to install on the planet.

That’s the complicated direction we’re headed today, the S&S cam installation, the S&S pushrods, the Compu-Fire system install, and the whole unit detailed by Heather New, of New Line engraving.

First, I pulled the Thunderheart ignition, which I grounded to the bottom of the transmission, and we pulled the ignition cam sensor off the front of the engine.

Next, we pulled the pushrod caps and clipped off the pushrods with an old set of shop bolt cutters. The cutters were so old, I had to disassemble the cutters, grind the jaws, learn how to adjust the jaw alignment, and re-assemble the cutters. They worked fine. The S&S instructions always call for disconnecting the battery, which is a damn good idea. It’s always a good idea to run the engine to top dead center (TDC) before clipping the pushrods, so there’s a minimum of pressure on the rods and parts aren’t jettisoned around the shop.

With the stock non-adjustable pushrods out of the way, we could remove the cam, which was also an S&S unit 35-0157. We were going to replace it with an S&S 561V , part number #33-5076 configuration, which was recommended by Frank Aliano of BlackHawk Motorworks in Florida. He has studied and built products for the bottlecap Indian engines for years.

I removed the cam plate fasteners and carefully removed the plates. The BlackHawk Cone came with replacement gaskets and O-rings, but I was careful not to damage anything. The stock S&S cam slipped right out of place, along with the thrust washers. I dug around for more replacement thrust washers for setting up the proper cam clearance.

You need to read the S&S cam installation instructions closely. Depending on the year, the cam lobe height, the model, engine size, etc., you may need to follow different portions of the directions. For instance, S&S recommends that you replace the cam bearings in 1992 and later big twin engines with a Torrington bearing, which has a higher radial load rating and can handle the performance stress.

I replaced the cam several times and checked the clearance with various thrust washers. S&S calls for an endplay measurement of .005-.015. This CrazyHorse 100-inch monster has the new oil pump mounted to the front of the motor, so there was no breather gear alignment issue. I thought it was a breeze and aligned the cam dot with the pinion bearing. There was also a red paint mark on the pinion gear about two teeth from the alignment dot. The red mark was there for gear size when the engine was originally built, not alignment.

But after I bolted up the cam plate, I questioned my alignment and removed the plate again. The cam had two marks on it. One was for a breather and the other for the pinion gear. I needed to make sure I was using the proper indicator for pinion gear alignment.

I ducked through this process several times. Another stumbling block surfaced: the lifters didn’t stay securely in the lifter stools. In the old days, solid lifters stuck well above the stools, so they could be held by hand or with a rubberband while the cam and thrust washers were replaced. I monkeyed with this, even removed the rear lifter stool so I could check the endplay and push two lifters out of the way. Ultimately, a sharpened piece of welding rod, bent just so, helped with the process of holding the cam followers in line.

I bolted up the new cam chest plate, with new O-rings. I made sure to oil the cam bearing surfaces. I had a set of standard S&S adjustable pushrods, which require removing the rocker arm assemblies in an Evo configuration and dropping in the pushrods from the top. I anticipated a problem with this endeavor and ordered a set of S&S Quickee Pushrods for this application. I didn’t want to mess with the engine to create the clearance to remove the rear rocker box.

Again, when I received the instructions, they were broken down for virtually every model available, from Buells to Panheads. I went with the 1984-1999 Big Twin instructions, which call for rotating the engine until the front piston is as top of its stroke, with both front lifters at their lowest position (TDCC–top dead center, compression stroke). If you look in the timing hole of the Crazy Horse engine, a black dot indent emerges at TDCC, so it was a breeze to find. I cleaned the pushrod tubes and replace the O-rings with a light coat of oil, inserted the new pushrods through the tube assemblies, and installed each one in the proper position.

I extended the adjusting screw to remove all the lash in the pushrod, then compressed the hydraulic unit in the exhaust lifter four complete turns or 24 flats, then tightened the lock nut (Frank recommended 4.25 turns). Then you are required to wait 5 to 10 minutes before adjusting the intake pushrod, so the valves don’t run into each other. After the waiting period, the pushrods should turn with fingertips.

I repeated the above procedure for the rear cylinder, and then replaced the cover clips and spark plugs. The instructions called to starting the motorcycle and checking for leaks. That’s good info. I blew oil all over the place before I discovered a pushrod cover that hadn’t seated properly.

Here are a couple of helpful warnings. First, if you are unsure about the lifters, here’s a way to check it. If you adjust the pushrod down four turns and wait, then try to turn it with your fingertips, and it doesn’t turn, you have hydro-solids.

Next, S&S Quickee pushrods for all big twin engines contain two long and two short pushrods (exhaust-long, intake-short). All Sportster models and Twin Cam 88 pushrods are the same length.

Now I could install the Compu-Fire ignition system. I left the engine in the TDC position for this maneuver. Compu-Fire has several systems, including single fire, dual-fire, and kick-start units. You can remove your point system and drop in one of these puppies in a flash. The system is a breeze to tune and it’s and all-in-one unit in the cone.

I’ve known the boss of Compu-Fire, Martin Tesh, for a couple of decades. He knows his shit when it comes to these simple, easy-to-tune, solid-state units. The unit comes with complete instructions, but basically, you replace the cam plate, install the ignition plate in the cone with a drop of Loctite, and run the wiring harness to the coil. Install three wires, tune the bastard with the supplied magnets, and you’re good to go. It even has switch settings to allow you to adjust the timing curve at 35 degrees before top dead center at 1500 rpm, to 35 degrees at 3500 or 4,000 rpm, depending on the model. You flick a switch, test ride it, and it’s set.

Here are the official Compu-Fire ignition installation requirements. First, I cleaned out the pristine Black Hawk timing cavity. I didn’t need to worry about the seal, it was brand-new. I installed the trigger with the long supplied Allen screw, and checked the gap between the trigger and the ignition plate. It seemed excessive, so I checked it again, and installed the supplied shim to tighten the gap. I aligned the trigger with the notch and torqued the Allen screw to 25 inch-pounds. The large round TDC indicator ding in the flywheel was still centered in the timing hole, so I was good to go for timing.

Just to be sure, the locating cam notch falls in the same place for every big twin cam, if the TDC mark is on the compression stroke. It always comes up at 7:00, so I checked it and was good to go. If it wasn’t, I needed to run the engine over one more time to be on the correct compression stroke. It was time to set the timing.

The directions called for turning the ignition switch off and reconnecting the ground wire to the battery. The instructions called for stripping the Compu-Fire red wire and temporarily connecting it to the battery positive terminal. I rotated the timing plate counterclockwise to the full retarded position. The Accu-Ray timing light may be on or off when you start this procedure. I used the disc magnets to turn it off and on by swiping them across the timing plate. It’s like magic. I turned the light off, then rotated the plate clockwise until it popped back on. I did this several times until I could lock the plate in the exact spot where the light came on.

Frank, at Black Hawk suggested that I rotate the plate a hair past the light-on spot to advance the timing slightly. Then I locked the plate down and I was done. Except to install the new Heather New engraved timing plate cover.

I disconnected the hot lead, and then wired the Compu-Fire ignition system in place according to the single-fire wiring diagram with a new Compu-fire single-unit, single-fire coil.

Okay, so I fired the beast up and went for a ride. Same problem. It blubbered at mid-range. It had to be a carburetor issue, so I yanked the S&S and installed a Mikuni 42-mm slide carb. I pulled it out onto the street, fired it up, adjusted the mid range air nozzle and the idle screw, and slammed the tank shifter into first. She popped but ran like a top.

That did it. It had to be a jetting issue, but then an uncustomary California storm rolled in, and it rained solid for a week. Hell, it’s rained for six weeks in Brisbane, Australia. And we thought we had flooding issues. I’ve been working with Paul Cavallo and his teams at Spitfire on our 2011 bike build efforts. I’ve had the privilege to speak often to his main builder, Larry Scrotum, a guy who has been building bikes for as long as I’ve been writing about them. Just recently, during a break in the weather, I mentioned my problem to him, and he was the first to come up with real solutions.

It could still be the Crime scene air cleaner and the way it’s positioned, leaving the choke vent open. He says the air rushing over it causes a problem with the fuel delivery inside. I needed to block off the outside vent and take the Allen screw out of the underside of the body adjacent to the vent. I’ll let you know what happens next. He also made a tuning suggestion regarding the air bleed vent in the float bowel. I’ll let you know the outcome.

Contacts:

CrazyHorse

http://www.crazyhorsemotorcycles.com/

Black Hawk Motorworks

http://www.blackhawkmotorworks.com/

New-Line Engraving

http://www.new-lineengraving.com/

Compu-Fire

http://www.compufire.com/

Sturgis Shovel Part 9

By Robin Technologies |

This is strange. I’m writing several Sturgis Chop Techs after I returned from Sturgis. I’ll try to remedy that in the future, but we were so damn busy trying to complete the bike and run Bikernet, we didn’t keep up on the techs. Many apologies.

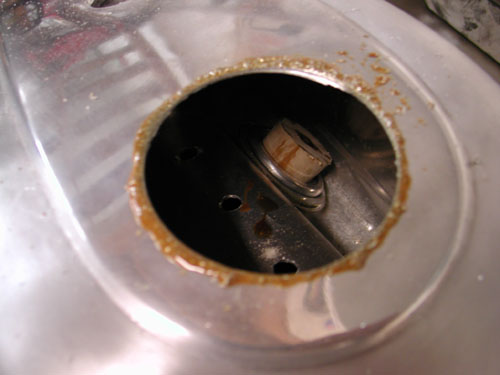

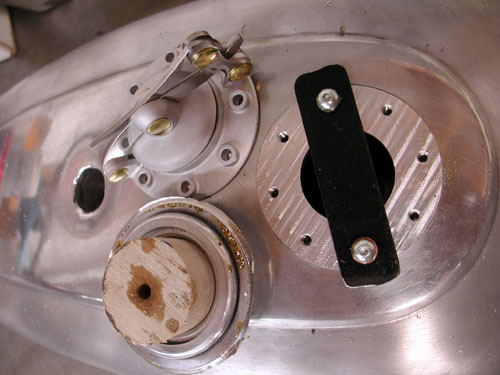

This piece covers the installation of the hot Speedster cap from Crime Scene Choppers in the modified stock XR 750 factory tank. Later, you’ll discover, that this highly modified, strengthened and extra rubber mounted beast was my Sturgis nemesis. But more on that later.

We added rubber-mounted bungs to the back of the tank. I moved the petcock to the rear and filled the center for a 2.76-gallon gas capacity before it hit reserve. I doubt that it contained more than a quarter tank of reserve, so I’ll toss it a 3-gallon total gas capacity.

Oh, I need to thank Cyril Huze, who designs beautiful steel tanks for the opportunity to experience an aluminum tank once more. He suggested this classic for the Sturgis effort.

I’m not holding it against Cyril. He’s a master and I’m the bungler for attempting aluminum on a 93-inch rigid S&S hot rod. As you’ll see the vibration aspects came from several sources that I could have remedied. It’s all just a roll of the dice.

When I received the Speedster cap I drug the cap and tank down the street, about three doors, to Bill Hall’s Welding. He handles my aluminum welding, since I don’t have a TIG welding system. I’ve got the rest, but not TIG. I would highly suggest a TIG system for quality welding capacity and good looking welds. It’s much like welding with a torch, so you’re certain of the bead and depth of penetration.

Bill’s a retired designer who enjoys welding and fuckin’ with his customers. “How are you going to drill the hole for the bung,” he asked?

I was thinking about die-grinders and files. I knew it would make a mess. Bill hooked me up with a 3-inch hole saw. He suggested that we hit a marine store for a tapered dowel pin (used for plugging holes in the leaking hulls).

The key was to drill a perfectly centered ¼-inch hole to maintain a center approach to the cap bunghole. I drilled it and then ran the tapered wood dowel into the tank.

Then we set the tank on a pad on the drill press platform and lined up the hole saw. I used plenty of cutting oil on the edge of the blade and aluminum face to prevent the tank from snagging or catching. I knew how tender the surface of the tank was. We oiled the hole in the tapered wooden plug and carefully went to work. Bill’s formula worked like a charm.

Next, we needed a tool to hold the Crime Scene Speedster bung in place. I grabbed a piece of strap, drilled a hole or two and mounted it with the supplied hardware, which was brass. You can order the cap with several styles of fasteners for your application.

It was off to Bill’s for welding. While the gaping 3-inch hole was available I could have made a tapping tool and tapped out any imperfections in the tank walls. I dinged it way back in the beginning and never got around to fixing it. I left her be, as if it was the first injury and she needed to stay. I know it’s one of those wild superstitions.

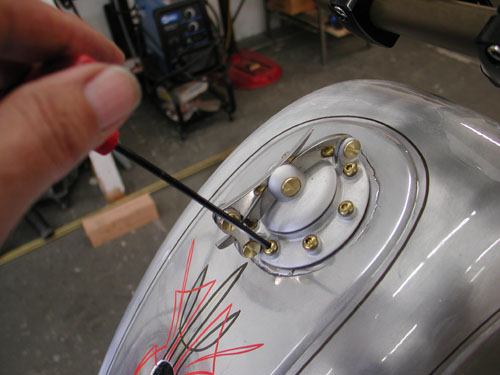

Okay, so during the “read the directions” phase, I noticed the bit about a non-vented tank. I would need to drill a tiny, cunt-hair hole in the cap of the tank. I discovered that I actually had such a tiny fuckin’ drill and dug it out. I had to find a chuck that pinched down to that size. Then I had a wise ass notion to drill the initial hole about 1/8 inch in diameter, since drilling with hair-thin bits causes easy drill bit breaks. The thinner the surface the better.

So, I initially drilled the inside of the cap with a 1/8-inch drill and drilled right through—Bummer. Ultimately I tapped the cap with a 10-32 then drilled the stainless Allen stud with the tiny drill bit. Then I screwed the stud into place and the job was finished.

After Bill welded the bung into place it was my job to grind the welds down and ship the tank to Foremost Powder for a clear coat. I hit the big spots with a grinding tool. I tried my damnest to take only meat off the welds and not off the surrounding tanks surface.

Next I used small emery discs to carve at the aluminum bead. I also smoothed some of the welds on the front of the tank where we filled the tunnel for additional gas capacity.

This shows the different grinding phases to reach a level that’s still strong with weld bead but handsome enough to live with. This was an interesting effort, since no bondo or thick urethane would be applied, covering a myriad of mistakes. This was the final stage before clear powder from Foremost in Gardenia, California.

After this stage I polished the panels of the tank and hauled it off to the powder masters. There’s one other process I need to explain. I made every effort to clean the tank of debris and shavings. I also made sure to run a gas filter. I still had problems, which I will explain in my Sturgis Saga. They were easily remedied through Lee Chaffin at Mikuni. Just needed to dial the right number.

This shot was taken after powder and pin striping when I installed the gasket, decided which direction I wanted the cap to face and screwed the brass fasteners down. The cap worked flawlessly all the way to the Black Hills.

Sturgis Shovel Part 5

By Robin Technologies |

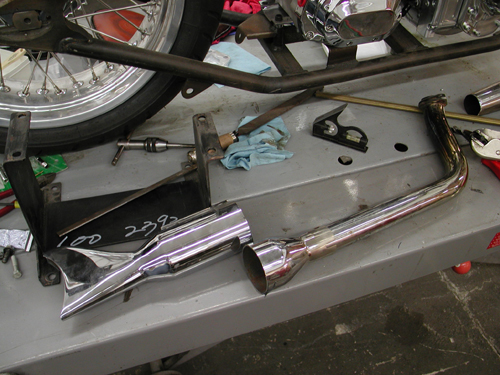

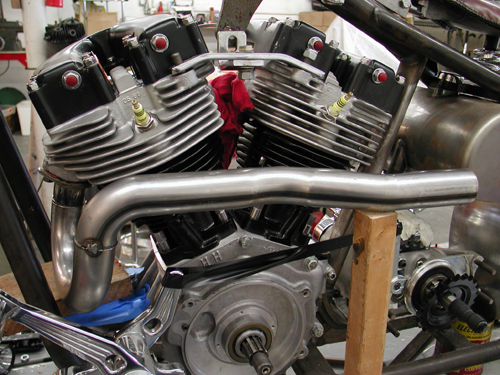

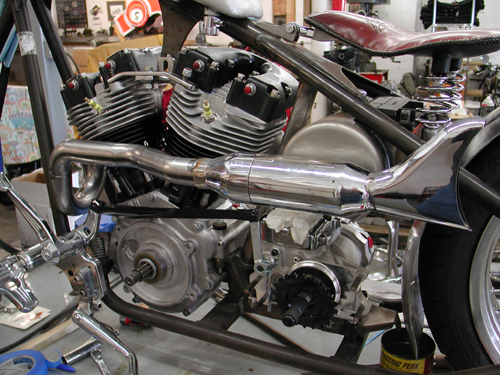

Helluva weekend. Anytime there's lots of motorcycle carnage,sex, whiskey and writing, I'm all for it. Maybe it's Valentines Daycreeping up. Make a note. Here's the deal on the Sturgis Shovelhead. Sincethe engine was in and mounted I went to work on the exhaust system,then seat mounting, position and played with the bars. I made a runto a local steel joint, because I had a notion that I doubt will worknow, but I'm still investigatin'.

Let's hit the highlights. I'm fortunate to have a young,talented fabricator/builder who I'm sharing ideas and resources with.Kent from Lucky Devil Metal Works in Houston is on the phone dailyfor tips and knowledge sharing. It's damn healthy to have someone whois in the trenches daily to assist. In fact I had a couple ofcrucial metallurgy question that morning, but let's hit what Iaccomplished.

A crucial aspect of building any bike is planning. That'snot to say all my eggs are in a row. We'll see, but the more you canaccommodate, the less redo's will be necessary. Also, don't throwanything away. That junk part might be a critical bracket tomorrow. Idug through my partially organized pipe bin and found a set of oldglass pack, shorty muffler, shot gun pipes. I could use the rear one.I decided, since noise issues are a concern and performance issue area constant priority, I would build a set of shorty mufflers withBandit tuned baffles.

Then I spotted the fishtips in the pile and myconsideration changed. I dug further. Kenny Price from Samson allowedme to dig through his warranty bin when I was looking for stanchionsfor my Bikernet office railing. I remembered touring mufflers withfish tips, I kept digging.

Sure enough I had a set and in quick movesI sliced them into chunks. You know me, I'm a gambler. I cut themwith no methodology in mind past the size and looks, but I came uplucky. Samson designed a baffle system with a cone at the front toguide exhaust pulses into the baffle and it seems to be working fortouring applications. I cut off that portion and discarded themajority of the baffle. But there was still 2 inches of baffle and astandard donut in the rear of the muffler. That's where fate movedit's evil hand over Richard Kimball again. Or in other words I rolledthe dice.

I spoke to Kendall Johnson recently and he told me aboutperformance stepped exhaust systems and reversion cones used to tunesystems at the rear of the pipe. I couldn't make this donut move upand back, but I had the makings of a reversion cone at the stern.With a torch I cut out the remaining baffle, then after speaking withthe HOT BIKE staff member, Craig Murrow, for a reversion cone descriptionI knockout out the remaining baffle, then with various cutting andgrinding cones I formed and smooth departure for the exhaust pulses.Then I had to remove the old touring mounts with a die-grinder andthey were ready to weld.

The rear pipe was comparatively easy since the pipe wasalready made except for the muffler and brackets. Shovelheads arenotorious for louse exhaust manifold connections and tearing out thesingle stud, so I wanted to mount them in the front and rear for asolid, secure connection. The only port for the connection at thefront was the oil bag. That was a bad choice and I'll run a bracket off the seat post before all is said and etched in stone.

I had to make sure the pipe could be removed with the tabs onthe bottom, then I spaced the tabs apart with a heat sink material. Imay use Teflon, then the notion that the oil bag is rubbermountedfloated to the surface. What bearing would that have on thiscoupling? Hell the frame will vibrate like a mad dog. I'm stillquestioning that link, but we'll see, maybe a spring between the tabs? The final decision was the seat post bracket to come.

There was one other pipe design consideration–the length.I try to keep the pipes somewhat equal and between 32 and 38 inches.Buster's Sportster runs sharp and crisp with his hand-made 38-inchesfrom the Bikernet Headquarters, as seen in Street Chopper. So Idesigned this pipe to be 38-inches and not protrude past the tire. Mygoal was to make the front pipe curve out the other side and be ofequal length.

At the end of Friday night, one pipe was complete, toolswere scattered all over the shop and I had a couple of Hooker Headerchunks of 1 3/4 pipes segments cut and was fooling with the frontheader. The front was tricky as hell. I wanted to scoop out the leftside of the bike, which added length. I also had a bitchin Rohm Engineering oil filter/cooler system that mounts to the front motormounts and aims the filter at the ground for ease of removal anddraining. The pipe had to clear it significantly. This puppy was alifesaver. I planned to run an oil cooler (Shovelheads run hot) andfilter, for a lasting driveline and more oil capacity. My originalplan called for old school mounting on either side of the oil bag.This eliminated all of that and the plumbing for two elements, the cooler and the filter, wasreduced to one hot looking job in front of the engine for maximum cooling.

I spentall day long on Saturday, dodging the phone and working in thegarage. I had all the tools and materials I needed, even two new setsof welding glasses, which came in damn handy. The trick was to lineup the pipes, make all the right decisions, hope for the best andtack 'em. I did and with a level I constantly compared the pipe tothe top of the lift. The spacing worked out fine.

I cleared the top of the Rohm bitchin' oil cooler/filter mounthopefully by enough to allow the pipe slip down and out of the head (I was recommended to use a CCI Filter part number 270126).I tacked the tab with a spacer between the two for some jiggle room.And I made damn sure that the pipe tab was below the frame tab. Atthe back, the muffler was fabricated the same as the other one with aslight exception.

I shaped the reversion cone the same, cut off thetouring mounts and ground the tabs. Then I used a couple of V-blocksto hold it perfectly in line for tacking the halves together. Then Isliced off the crush tabs on the front of the Samson tapered muffler.They were wider and different than the other side, so I cut them off.You'll notice the difference, if you check both side.

The front parts of the pipe were Hooter elements and theyare smooth mandrel bent segments. I used another one for joggedstraight piece between the muffler and the head. I took the 13/4-inch exhaust to my Muffler Master bender and bent it slightly oneway, then reversed the sucka and bent it the other way. It fit like adream and looped out enough to pass the oil bag. I used Hooker headeralignment sleeves to hold the front pieces in perfect alignment. Donedeal, I tacked them, constantly comparing the level with the lift,the pipes then the muffler. After the tacking was secure, another tabwelded to the frame, avoiding the oil bag (a Lucky Devil concern,since the oil bag is rubbermounted), then all elements wererechecked, I removed both pipes and MIG welded them as complete aspossible.

I find that MIG welding is a pain and blows holes in pipes easily.I also discovered that after I MIG weld a pipe I can flow the weldeasily with a torch and smooth out all the welds, fix holes and fillgaps. I actually found a piece of old steel rod, not much bigger thana piece of wire. I usually use old coat hanger, but it pops andwheezes from the paint coating.

After the pipes were welded, flowedand checked twice, I ground all the surfaces with an emery disc andpainted them with whatever barbecue heat paint I had laying around.The lovely Layla is currently on her way back from Home Depot withsome flat black heat paint. We'll see how that works.

Kent from Devil hand fabricated the seat pan, brackets andbungs. I set them up and welded the parts in place. Then it was timeto roll the bike off the lift and see how she fit and where I mightneed heat shields. I discovered a couple of things. Yes, the scootwould require left side heat shields and nothing on the right. I alsotested my notion to sculpt claws out of brass, unsuccessfully.

I also found that the existing bars wouldn't cut it. Igrabbed the old '48 Panhead TT-bars, narrowed them by 4 inches, and Isorta like them.

Okay, so I grappled with the sculpting business fora couple of hours and discovered that I can't control the brass likeI can steel. I spoke to Kent from Lucky Devil and he recommended thatI try TIG Silicon Bronze rod. I'll try that next week. In themeantime, my first brass sculpting attempt ended up on the shop door.Let's get the hell out of here.

Ride forever,

–Bandit

5-Ball Factory Racer Closing in on New Cam and Ignition

By Robin Technologies |

We were fortunate to hook up with Heather New, of New-Line Engraving several years ago. Since I was about to switch out my CrazyHorse engine ignition with a Blackhawk Motorworks cone cover I needed to come up with a classic point cover for the new unit and the 5-Ball Factory Racer. It was a natural choice to send her a chunk of aluminum, or I shoulda sent a piece of brass, but oh well. Either way I knew she would bring the project to life.

Heather started engraving in a small shop in downtown Edmonton in the Early 80’s, where she took care of over 100 jewelry stores. “I was engraving everything from I.D. bracelets to wine goblets to pocket watches, and more,” said the raving redhead, “items which other engravers said could not be done, I soon learned to do!!! This was when I first met Frank.”

Frank Gurney was (and still is) the best Hand-Engraver in Canada. “He is a true artist and craftsman, and along with the Alberta Apprenticeship Program, arranged for me to be his understudy,” Heather said. “I was thrilled!!! I learned so much from Frank in those years, confidence, trouble-shooting, and above all HUMOR!!!! We spent hours working and laughing (hoy-deedle-doy!!). He taught me so many things before he eventually retired out near Victoria, B.C.”

She then moved on to the largest Jewelry stores in Canada. “I was doing all of their machine engraving, as well as custom wedding bands, and one-of-a-kind jewelry pieces,” Heather said. “They treated me like gold, and I will always be thankful for the kindness I experienced there. I relocated near Calgary, Alberta, and began working for a gigantic company with more talent than I had ever seen gathered in one place. I naturally did the engraving there, and also moved on to operating CNC machines, and hand-carving moulds used in casting.” She became a programmer, writing the programs, which would later be used by the CNC machines to cut the actual moulds.

She started New-Line Engraving in the summer of 2005. “I hand-carved an inspection cover for my good buddy ‘Chicken’ and with her over-whelming encouragement, (she cried when she saw it) I decided to branch out into custom bike carving too (after all, a derby cover is just like a signet ring, only BIGGER.”

So here’s how the short, two-week process rolled:

Cover the piece in white water-soluble paint, and transfer the artwork onto the surface

I highlight the general outline, scratching the paint leaves a more permanent mark than pencil, and you don’t rub it off as you work!

For removing large areas you can try a dermal, but they tend to vibrate too much for any fine work…I used small gravers hooked into a pin-vice to cut in between the letters,

as this cover was done mostly under a microscope.

I also use fine sandpaper, jeweler’s files, and burnishers to “round-off” curves (as seen on her legs), and give some dimension to whatever artwork you are dealing with…

Details like hair, the features in the face, and fine shading are all done with fine gravers and files.

I then add an aluminum-oxidizing agent, which blackens the entire piece. When it is re-polished, the highest surfaces will become shiny again, while the black remains in all the nooks and crannies of the background. (I only do this by hand—a buffing machine can remove hours of work in a heartbeat!!)

“If anyone out there in Cyberspace wants to give it a whirl, I am always here with support and tips,” said Heather

Sources:

NewLine Engraving: http://www.new-lineengraving.com/

Blackhawk Motorworks:

http://www.blackhawkmotorworks.com/

Compu-Fire Ignitions: http://www.compufire.com/

Custom Chrome:

S&S:

Sturgis Shovel Part 8

By Robin Technologies |

My first move began with a correction. I removed the exhaust pipe tab welded to the oil bag. The oilcan is rubber mounted, the exhaust pipe generated severe heat and the pipe system needs to be solidly mounted. It had to go. Actually Kent from Lucky Devil Metal Works in Houston tried not to mention the false move, but his frown gave it away. Or was it that question? “Is your rear pipe really mounted to the fuckin’ oil bag,” Kent said tentatively?

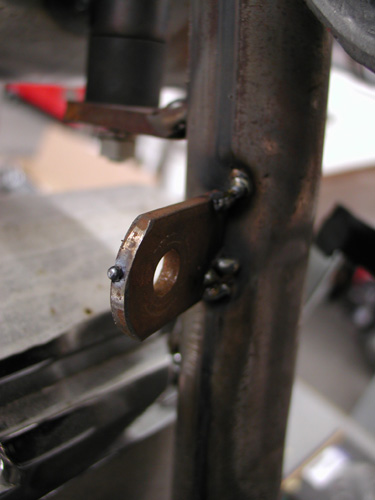

I discovered that the pipe exits the head close to the seat post and worked on a pipe connection there. There are a couple of rules in making pipes that I need to abide by. I needed to remove the pipe once in awhile, so I needed the pipe tab to be on the outside of the frame tab. Often mounting required slack, so I dug around for 1/16-inch washers to run between the tabs. That way when the fasteners are removed there’s some slack to pull the pipe free.

I worked with the pipe fully in place then tacked the seat post tab. Below is the tab tacked to the pipe. Then the tab welded in my shitty MIG welding fashion. I should slow down and clean the base metals more. I generally grind a bevel into the tabs for greater weld penetration. The welds are strong, just not handsome.

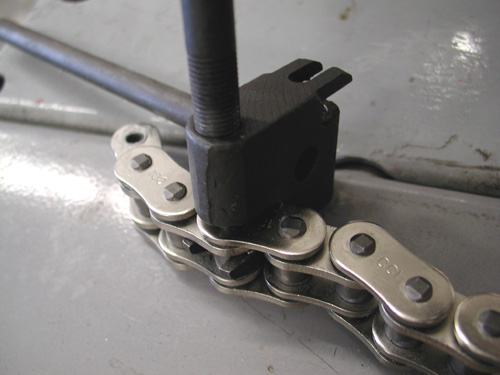

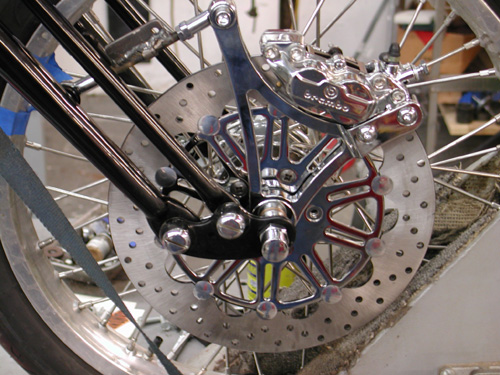

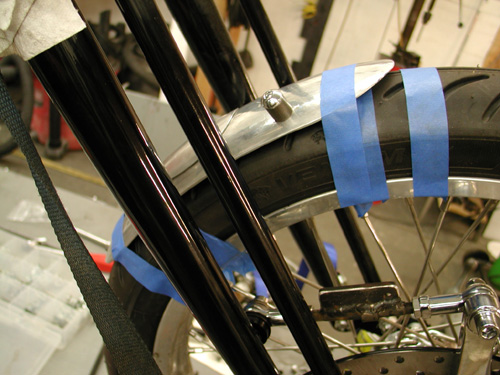

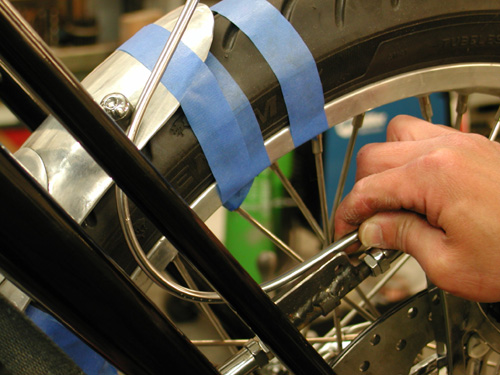

Next I needed to attach the Lucky Devil rear fender, align the rear wheel and cut the chain to fit. But first I needed to center the wheel in the frame, sorta. The custom Paughco frame is designed and manufactured to hold a belt pulley and a 180 Avon Tyre. That prevented me from measuring between the frame rails. I needed a straight line down the center of the frame backbone. It’s not incredibly accurate but close to draw a fabic or nylon line down the tube. Then with Doherty space kit and the seal spacers that came with the Custom Chrome aluminum and stainless spoke wheels, plus the Brembo brake caliper bracket, I aligned the wheel.

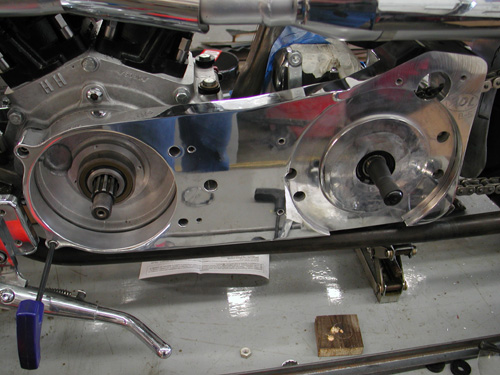

Before I cut the Rev Tech chain I installed the BDL Belt inner primary and pulled the engine and transmission into place which determined exact spacing. I know I covered this aspect somewhat a couple of chapters ago. There’s been some heavy drinking in the meantime, so if I lose track, it’s on Jack.

I centered the wheel in the chain adjustment slot to give me slack either way. Then I finally cut the chain with a JIMS tool.

I spoke to a couple of guys about sprockets and was told that this contraption will hold a sprocket nut from coming loose better than simply Allen screws in the Custom Chrome sprocket. I may use it or not. Haven’t decided yet.

The reason this is altered is that it’s for a pulley and a different era. Add that to the fact that I flopped the dished sprocket over to space the chain away from the tire. That aspect worked perfectly.

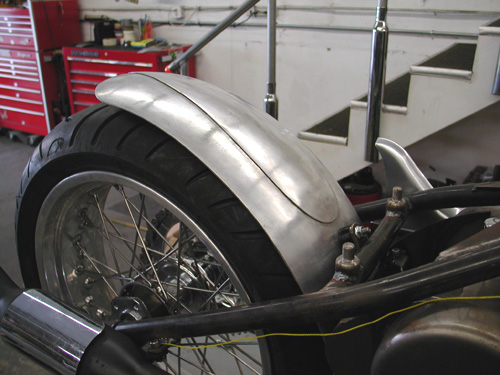

I decided that since the tank was rubber mounted and aluminum won’t flex as well as steel that I would attempt to rubber mount aspects of rear Luck Devil fender. Kent designed and handmade the fenders to match aspects of the XR 750 tank.

Cyril Huze sent me several grommets to work from and this pair are from some late model Sportster application. I measured the O.D. on the center portion and discovered that I needed ½-inch holes in the fender which I drilled after I had mocked up the fender in place, ground a clearance strip for the chain and stood back several times. Arlen Ness once told me that he used a chain wrapped over a tire to space a fender. I needed enough space for fasteners under the fender and some chain adjustment slack either way.

I moved the fender up and back, and side-to-side several times before making any hole-drilling marks. I was a nervous wreck. Ya don’t mess with the Devil’s fender. I finally drilled a half-inch hole, and smoothed the edges, in the bottom of the fender then at the crossover tube. I worked in the rubber with a dab of oil and bolted the bottom stainless bolt in place.

The Sportster grommets have metal inserts, which make them easier to install. With a couple of spacers in place the fastener held the center tab for tacking.

Here’s where it got tricky. I’ve been bending metal with a torch for years. Never improved my technique. Just the other day, a month after I built this fender rail system, I bought a small strap or tube-bending tool. Wish I had it when I went after this project.

First I built the fender strap out of a piece of exhaust pipe bracket. It came with two 3/8-inch coarse tapped inserts in each end. My plan was to build a fender rail system with tubing so I could adapt a couple of running lights on the tips. I carefully bent and drilled the strap and fender.

Then I bent the tubing fender rails to fit over the chain and tacked tab to the Paughco frame. One item I often attempt to use is a level. I’ll level the frame from side to side, then strive to keep all the other elements level. It helps.

Here’s a perfect example. As I finished my welding chores, I got on a roll. I thought– wouldn’t it be cool to weld the fender bolts in place from the bottom. They would never come loose. Note the angle. There was no way they would ever return through their mounting locations. I was forced to grind them off and clean the holes.

Here’s the finished fender rail system. I drilled holes in the frame and the rails to run wires. I still haven’t found the perfect running light style that rocks my boat and will afford me enough room to use the proper fasteners. Hang on!

Sturgis Shovel Part 7

By Robin Technologies |

Brembo has a solid worldwide reputation, and I ran into a hot looking Brembo representative at an illustrious bike function and decide I’d give them a try. They’re hot and ready to rock. The only items I needed were the locking nuts for the back of the rotors bolts and the springer axle spacer. This set-up was designed for a stock springer replacement.

Because of the wild, light, taper-legged Paughco Springer my hiem joint link wasn’t long enough and I bastardized two fine bolts together temporarily. At that point I wasn’t considering a front fender. There are two aspects of chopperdom that I have a tough time working around. Bikes need front fenders and brakes. Can’t ride ‘em much without those two bastards. Even in the old days I ran front fenders, Avon Tyres and front brakes.

Chris Kallas came over at just the right moment. He’s as old at riding as I am and an artist. We’ve featured his work in special reports. He knows his bike shit and I’ve been trying to convince him to see Jim Murillo about a job. Jim has a paint shop in Torrance, but he’s not the graphics guy, Chris is.

As usual, about the time I think it’s going to be easy, the devil pops up on my shoulder. Kent, from Lucky Devil Metal Works in Houston called, “What are you going to do about a front fender,” he said? “Yeah, that’s what I thought. I’ll send you some shots of my springer front fenders.” He hung up and Chris looked at me sorta strange.

”Who the hell was that,” he said?

”Never mind,” I said flipping my computer on. Kent developed a system of mounting springer front fenders that’s clean as a whistle and odd as only the devil would make it. An engineer wrote Bikernet when I first featured his wild notion and chewed us out. “That idea’s not worth the powder the blow it to hell,” he shouted.

At first I thought he was correct, but the more I considered it, the more I determined that he was wrong. The caliper follows the line of the rotor, so the fender will follow the circumference of the Avon tire. Of course when I stepped into the ring to create a similar configuration I couldn’t do it like the Devil does. The Brembo caliper runs too far ahead of the rotor to mount the fender so we ran carefully designed struts off the brake linkage. Chris drew up the plan, then bent struts out of coat hanger for a guide.

We constantly tried fitment again and again before tacking them into place. I wouldn’t recommend this configuration to anyone. If you run struts off the caliper they’re solid. The heim joints allow the fender to fluctuate, especially side to side. I had to find a concave washer that would allow the heim joints to work up and down but not side to side.

Chris bent each rail to match in pure artistic form. Then I tacked them.

Kent built the front fender with threaded aluminum bungs underneath. I figured out some slender spacers to fit on top of the fender and tacked the rails to them. I must have welded them a dozen times trying to grab just enough rail, weld and spacer to prevent cracks.

There you have it. It’s wild, but will it last to the Badlands?

–Bandit

1928 Shovelhead Project Part III

By Robin Technologies |

The lovely Lena Fairless, who has threatened to marry Bandit (the sixth Mrs. Ball) and make him work for her folks at the Easyriders Dallas store, has been pushing to see that this 1928 Shovelhead project is completed in time for her wedding plans. Bandit doesn’t seem to move unless there’s a motorcycle and a woman involved. There’s just one problem in this case, which Lena is well aware of, she’s under age…

The other news on this project is that we now have a corporate sponsor, Ed Martin of Chrome Specialties, and a mentor, Chica, who builds bikes in Newport Beach, Calif. Chica built “Trick,” the old-time Sportster that Chrome Specialties is displaying at all the events it attends, such as Laughlin this month. Randy Simpson from Milwaukee Iron and Arlen Ness are also building spindly retro scoots with late-model drivelines. I spoke to Arlen the other day and he told me that a number of top builders in the country are building this style of beast for upcoming shows. Arlen is now building Sportster frames, sidecar frames and the tubs for these units. He’s sold 10 sets. Don Hotop is building aluminum tanks, so soon the parts for building these retro bikes will be even more available.

The contact stateside for the European parts we used is Fred Lange at (805) 937-4972. He has access to seats, fenders, front ends, tanks, headlights and more. Let’s see if we can pick up where we left off.

The frame is a stock rigid Panhead configuration from Paughco, with a stock, late-model Bad Boy front end. To drop the front slightly, Jim Stultz, Rick’s main fabricator/bike builder, used a KT components lowering kit to make the frame level because the newer springers are XA length. The retro tanks are sweat-brazed together and contain the oil in one half and the gas in the other. Unfortunately, the tanks did not fit the frame at all and had to be disassembled, cut and re-welded to fit. The fun part of such a round-the-town project is that it can be a true swap meet special once you have the basics in hand, and you can slip as far back into the retro world as you want. You can roll with chain or belt. You can use any old brakes you have around. Rick chose to use disc brakes and a chain, but he’s going with a jockey shift and internal throttle assembly from Chrome Specialties. The charging system will be state-of-the-art Compu-fire and the carburetor S&S. The engine and transmission were rebuilt from the ground up by JIMS machine and the engine cases are STD.

Both wheels are 21s for that spindly look. The handlebars were designed by Jim and bent by Milwaukee Iron. With the internal throttle cables, there will be a minimum of controls on the handlebars. Since the transmission was rebuilt with the notion that it would be electric start, an aluminum inner primary will be used with an old-time-looking tin outer primary that Rick picked up at a swap meet. Rick ordered a narrow Karata belt drive for the primary.

Jim sliced all the mounts off the frame except the front footpeg mounts, the engine and tranny mounts. Since the oil tank is part of the gas tanks, the only additional container would be for a battery to conceal a car-type marine ignition switch and a light/toggle switch.

“I try to fabricate components to be user friendly,” Jim said. He designed the battery box so it would only take two bolts out of the seat post and two out of the rear section and the whole pan will lift out through the top. The two sides covering the battery will meet in the middle in a flying wedge configuration, and Jim plans to build a top cap to conceal the battery from the area under the seat.

The steel gas tanks, once cleansed of the brass, were chopped and channeled to clear the rear head. The entire center of the tanks was removed to fit over the frame. Unfortunately that reduced the gas capacity to 1.5 gallons. The European threads in the cap bungs were tapped out of sync, so they had to be re-machined.

Lena teases Bandit with occasional shots from her mother’s digital camera. Next week we’ll discuss the mounting and installation of the Compu-fire ignition. Some members of the staff will be happy to see Bandit go to Texas, others, mostly the women, are bummed. He even called to see if he could ride it back to the coast and was told that it didn’t carry enough gas to get him out of town. Evidently the tank is Lena’s design.

–Wrench