Mudflap Girl FXRs Build, part 9

By Robin Technologies |

What a year, and we’re cranking on so many two-wheeled fronts. Both Mudflap Girl bikes are running and one is in the wind, but I’d better back up. You’re going to love this tech, and the ending.

I took the Mudflap Girl bike to Saddlemen during the holidays, at just the wrong time. They faced the holiday schedule, then dealer shows, including the Easyriders V-twin show, then Daytona, before the dust settled and the shop was calm enough to focus on a couple of custom seats.

Sure, the economy sucks, but you wouldn’t know it if you stumbled into their brick manufacturing facility in a Los Angles industrial community. The shop is cooking, building twice as many seats as last year, and adding 420 new seat part numbers. Tom Seymour, his partner, Dave Echert, and Avery Innis have stepped into the luggage arena for touring bikes, cruisers, and sport bikes. They designed a line of bag inserts, sissybar pads, tank and fender trim, you name it. If you’re going for a long ride, they have the product for you.

That’s just the tip of the chrome and leather iceberg. The Saddlemen team will attend 78 shows, and events this year, from Sturgis to flat track racing, with the marketing director, Ron Benfield in the lead. The family atmosphere in their facility started to impress me after a couple of visits. I met 25-year team members and their sons and cousins. In fact, Avery kindly took a liking to an old Bikernet buddy, Buster Cates, and offered him a position on the team. Buster owns and rides our Shrunken FXR to work every day.

Let’s cut to the seat-building chase. The Saddlemen team turned motorcycle seats into an engineered art form. They don’t just make cool seats but poured engineering into the mix for comfort and long-ride ability. They studied the use of medical gels, then the spinal relief channel, lumbar support, and foam and fabric functions. Now they make heated seats, and the heels-down seats for shorter riders. Several of these elements add time and substantial cost to the seat manufacturing process. Plus they always attempt to make their seats fit better than stock.

Saddlemen has a team of custom seat builders who carefully design seats for special applications, race bikes, and sometimes, ultimately production seats. I was impressed with the myriad of seat manufacturing processes and how the team handled each one. Jose, the senior custom seat designer, worked with us through the entire process. First, he verified the position of the seat and the position of the frame rails, which are not always entirely symmetrical. Then he determined the center of the fender. He carefully masked off the entire seat area, and then began to hand-form a sheath of 1/8-inch wax. It performs a couple of functions. First, it molds perfectly to the frame, and second, it affords a 1/8-inch clearance for fabric to fill during the final stage.

“Every motorcycle has a seat,” Avery said, “but there are multiple body styles.” Avery is the engineering, design, and customer relations guru. He worked for Suzuki and Honda for years, and rides touring bikes and enduros. “All body styles don’t fit the same seat or style of riding.”

The wax helped the seat to locate itself on the frame perfectly. With wax strips, Jose formed a small channel on the inside of the wax seat pan to allow for fasteners not to protrude. The channel is about ½-inch wide and 1/8-inch thick. When the channel was placed securely, Jose filled the wax-to-wax edges with clay to prevent resin from seeping under the wax channel.

After the first sheet of fiberglass was carefully laid over the wax and carefully coated with resin, we cut a dusty trail and planned to hook up the following week.

Day Two:

We returned to the shop. The doors open at 6:30 in the morning and shut down at 3:30. I found the timing to be very civilized. The staff can enjoy a comfortable afternoon at home. We didn’t roll into the shop until 10:00 and Jose was already cutting and shaping the fiberglass seat pan, with the seat hook brackets molded into the bottom of the pan. Fiberglass contains amazing strength, yet adds flexibility. They are the official seat maker of the AMA pro racing/flat track, and now road racing classes, and they make all of Steve Storz café racer kit seats for Sportsters. They also sponsor dozens of flat track racers, the 5-Ball Bonneville Racing team, the Jordon Race Team, and Lotus.

With the seat pan shaped perfectly for my goofy Mudflap Girl ignition key system, we peeled out once more, and returned the next week for foam shaping.

Day Three:

“This is the most impressive aspect to making a custom seat,” Buster said of the foam shaping process.

“The driving force is style,” Avery said, “then we add performance with the gel, the spinal relief channel, and lumbar support.” Initially, I shot for the coolest, cleanest design to feed my chopper soul, but realized I needed a long-distance rider for my future Sturgis runs. When the discussion of lumbar supports surfaced, my lip zipped tight. I didn’t want to step into the middle of the comfort engineering mix.

My goofy key position worked perfectly into the channel design. Jose cut and shaped the 1.5 inches of foam with highly sharpened kitchen knives and coarse emery discs. Avery and Jose discussed the sketches for the position of the channel and the gel. One inch of gel represents 3 inches of foam.

Here’s the company’s gel description: Almost two decades ago, Saddlemen was the innovator of SaddleGel for motorcycle seats, bringing over a gel technology widely used in medical applications.

Without question, SaddleGel is the most important breakthrough in motorcycle seating technology in decades. This amazing product will increase the amount of time you spend on your motorcycle, creating the comfort necessary to ride all day. Every type of riding is more enjoyable, from touring to dual sport, canyon carving to street cruising.

When it comes to motorcycle seat comfort technology, nothing compares to a Saddlemen seat with SaddleGel. The proprietary SaddleGel technology was gleaned from the medical industry with specific origins in wheelchair pads and hospital beds. The gel was used (and still is) to prevent bedsores for those confined to beds for long periods of time and for people in wheelchairs—some for their whole lives. Know anyone that rides as much as a person confined to a wheelchair?

In the early ‘90s, the experienced riders at Saddlemen figured out a way to incorporate all the benefits of gel into a motorcycle seat and quickly learned it was far more comfortable than standard seats for a variety of reasons. For one, SaddleGel isolates engine and road vibration, a common cause of rider fatigue. SaddleGel is a molded solid with fluid-like properties that will not slide to one side or move around in your seat like air or water in a plastic bag. Instead, the proprietary design eliminates pressure points at the hip bones and tail bone by evenly distributing your weight across the surface of the seat. Otherwise, pressure points or hot spots can hinder blood flow, causing pain and discomfort. Normal circulation is never lost on a seat with SaddleGel. It keeps your rear end comfortable on a long ride, and ready to respond quickly as road conditions change.

Saddlemen SaddleGel is extremely advantageous, but we were able to maximize its benefits by developing a seating comfort system around it. Our integrated seat designs include a selection of materials that work together to make our seats as comfortable as possible, while still giving your bike show-quality style.

Avery has a product formula he learned from the president of Suzuki in 1990 at a business philosophy conference. “Every product must be evaluated for styling, performance, and value,” Avery said. We discussed business notions and the alignment of the stars while Jose carefully shaped foam.

Day Four:

While I was missing in action, Jose refined the shape, inserted large segments of gel, and made a custom aluminum channel section. They need something to apply the upholstery to, and then fasten it to the bottom of the seat pan. Nothing is as easy as it seems. Then he added a final lather of breathing foam, only about ¼-inch thick, and we started to decide on the fabric and pattern.

“In the past, we all thought leather was the ultimate fabric,” Buster said, “but not so.” Learning the Saddlemen ropes fast, Buster discovered new, more resilient fabrics, stronger materials, and more comfortable weaves. Avery chose a long lasting carbon fiber weave for the front of the seat panels, then a brushed aluminum vinyl for the channel center and the lumbar region. They even planned to scan a Mudflap girl and embroidered her into the seal. The rear seat tab was positioned during the second layer of fiberglass. Avery chose another black vinyl for the back of the seat. It’s tough, has the delicate touch of skin, and will last.

Jose marked lines for fabric patterns, and next he would drill and counter-sink the custom aluminum panel before upholstery and placement down the center of the pan. He ensured that the gel was properly glued with their coveted water-based adhesive, used for all foam application. The thin layer of porous headliner foam acts as a visual detailing source for seat shaping and adds breathing, but it’s not long distance comfort foam. The Saddlemen-designed progressive foam and gel handled the tough job.

Here’s the Saddlemen description regarding the spinal channel system: Our Gel Channel line of seats for sport bikes are designed specifically for the rider that needs a seat that can do everything—canyon carving, track days, or commuting.

They feature Saddlemen’s Gel Channel (GC) technology (patent pending) that incorporates a split piece of SaddleGel and a channel in the base foam to relieve seating pressure on the perineal area, increase blood flow, and keep the rider in the saddle longer.

While another week sped past, the Saddlemen staff sewed the pattern pieces together with marine grade nylon and polyester, colorfast thread for sun tolerance and lasting durability.

I never imagined so much thought, engineering, product testing, selection, and creativity would go into a goddamn seat. But when you think about it, you’re almost as involved with the seat as you are with any other aspect of a motorcycle.

The call came: “The seat is finished and fine,” Buster said. “Come and get this puppy.”

We grabbed the new license plate, a new Aeromach mirror, a Bandit’s Dayroll packet full of tools, and peeled out. This wasn’t within the mantra of the Eddie Trotta break-in procedure. The well-organized Saddlemen facility was located about 10 miles from the Bikernet Interplanetary headquarters. We ran the driveline through several heat cycles, but it never felt the clunk of the BDL clutch allowing the JIMS 6-speed transmission drop into gear, or the Metalsport mag wheels and Avon tires skid across any dusty asphalt lanes.

The Mudflap Girl resided in the asphalt driveway, out front, as we pulled up to the Rancho Dominquez facility. For the first time, I swung my leg over the carefully detailed Saddlemen seat, and sat down, as if about to cut a dusty trail. I immediately felt at home.

While the Saddlemen gang hung out around my Mudflap Girl in their driveway and we warmed the H-D Evo engine, we tightened the leaky fuel filter, adjusted the position of the clutch lever, and then I dropped it in gear. It shifted so smooth, I didn’t know I was in first. I was slightly nervous as I rolled out of the driveway. The seat was amazing, but would I survive the virgin ride home?

Next, we will cover my son’s final build aspects, adjustments, and first ride. Hang on.

Spitfire

D&D Exhaust

Biker’s Choice

JIMS Machine

MetalSport

BDL/GMA

Wire Plus

Branch O’Keefe

Bennett’s Performance

Custom Cycle Engineering

Saddlemen

Bub

Progressive Suspension

Bennett’s Performance 2004 Dyna Build 106-Incher

By Robin Technologies |

Eric Bennett grabbed the shop door chain and hoisted the roll up door for the first time, in 2000. He started his mechanical career as a certified diesel mechanic with 60-weight always flowing through his blood stream. Finally, he gave into his entrepreneurial spirit and his desire to make motorcycles his life—he opened his own shop on Signal Hill. The rest is motorcycle history, much of it spent at the Bonneville Salt Flats with his dad, Bob.

He recently owned a modified twin cam FLH, but a customer made him a deal he couldn’t refuse, so he let it go. Then a deal on a Dyna surfaced and he made a quick move to snatch it. This time, he decided he would take it to the concrete and rebuild every aspect of the bike to be moderately fast, ultimately reliable, precise, and built with absolutely all the best mechanical intentions and components in mind. You get to see the 106-inch project unfold before your very eyes right here.

One of the benefits of running a service center in the largest city in Los Angeles County includes encountering every possible mechanical malady and the ability to research whatever solution might be necessary. Since LA is also the motorcycle media hub, he has constant opportunities to test anything new on the market. After working on Twin Cams since their introduction into the market in 1998, Eric has watched every configuration, modification, performance recipe, and model roll in and out of his shop.

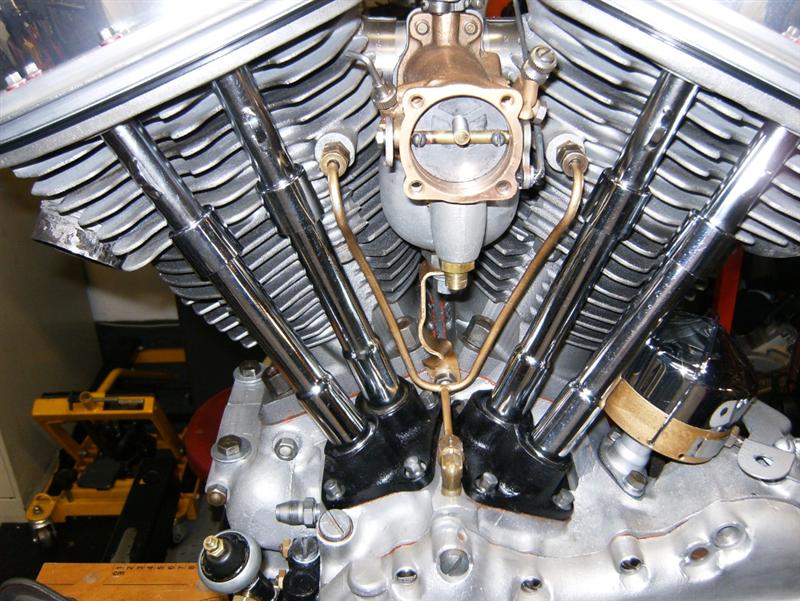

With this build he could pour every lesson and improvement into his own ride. It started as a bone stock 2004, 88 cubic inch TwinCam. Eric could choose from any hot rod configuration in the world, but he chose to roll with a 106-inch kit from S&S and Branch re-tuned heads. He started the process by installing a JIMS Timken conversion into his left case and welding his crankpin into the S&S lower end after it was balanced.

“With superior S&S flywheels, I didn’t need to monkey with the cases,” Eric said.

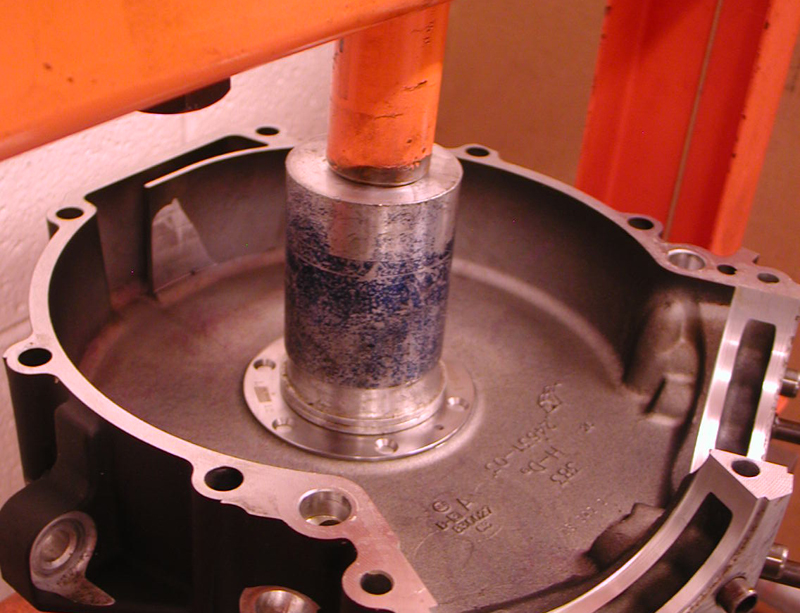

He bored the stock barrels from 3 ¾ to 3 7/8 inches and increased his stroke from 4 inches to 4.5. With JIMS tools he pressed in the JIMS race (using green Loctite) (9-59-1) while keeping his fixture perfectly flat and the hole in the race at 12 o’clock.

Using a JIMS fixture tool, he was able to drill guide holes in the case for Timken bearing and race oiling. The JIMS tool holds the drill and guides it. The drills are set to indicate the depth. Otherwise, he would need to use transfer punches and a milling machine. Then he used another JIMS tool to drill for the race fastener holes, and used tap guides to prevent misalignment.

“I’ve made tap guides for every size tap,” Eric said.

One of the benefits of the higher quality Timken lower end bearings is their ability to lock the lower-end into place.

“I have never seen a Timken bearing fail,” Eric said. Until recently Timken’s were used since 1957. “I’ve seen dozens of roller bearing failures!”

The cost saving shift to roller bearings started in 2003 during the 100th anniversary season. “The best Twin Cams were built in 2002,” Eric confirmed. “Better engines, still carbureted and with 1-inch axles for strength and stability.”

Eric used red Loctite on the race screws. He uses a tool for installing both Timken races at the same time. Kelly McKernnan, an amazing machinist out of Portland, Oregon, manufactured it.

The next phase included welding the S&S flywheels. Anytime Eric has a twin cam lower end out of a customer’s bike, he welds the crankpin in place with stainless TIG rod. It doesn’t create much heat and is not a structural weld; it just cements alignment and prevents shifting. He always checks the true after welding.

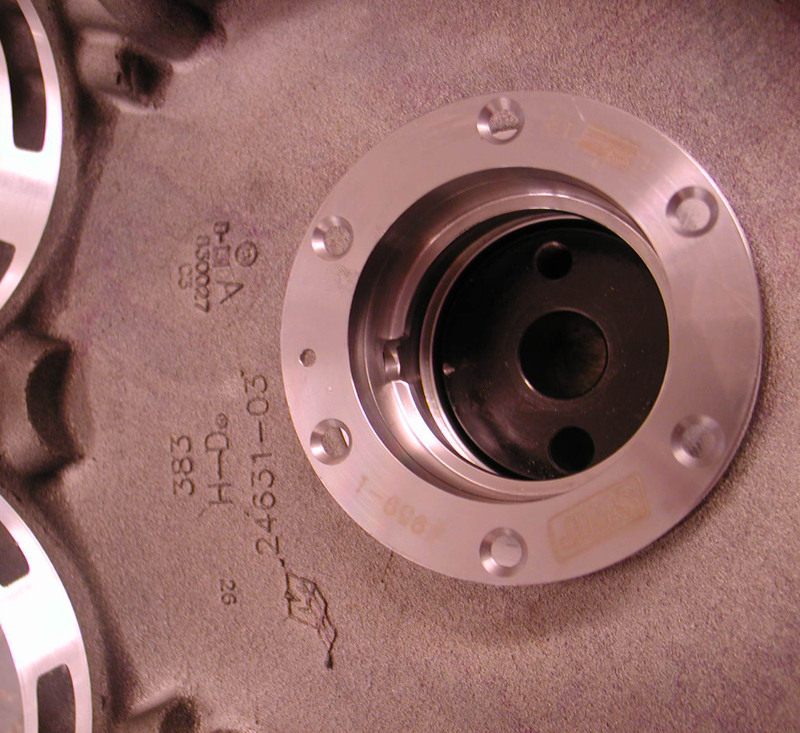

Next, he installed the Timken bearing by heating the race to expand it, and it slippped over the shaft easily. There is very little endplay in the shaft, just .001-.002-inch. Eric cinched down the top bearing with another JIMS tool, then pressed in the main seal and spacer with yet another JIMS tool.

At this point, we shifted to pressing the new S&S cam bearings into the new heavy-duty Screamin’ Eagle cam plate for hydraulic cam tensioners, but Eric chose to shift to an S&S gear drive system, so he blocked off the oil passages to the hydraulics.

He installed Torrington cam bearings in the right case prior to installing the new cams. His plan called for installing a D&D Bob Cat exhaust system, which is 20 pounds lighter than a stock exhaust. D&D pipes come bolted together with all spring clips, flanges, and heat shields in place. “They take like two minutes to install,” Eric said.

“It’s the easiest system I have ever installed,” Eric said. “It comes with the all the components needed and the heat shields in place. No shimming is necessary or egg shaping holes.”

Day 2

We took a break for the day and grabbed a beer. But the next day, Eric installed a heavy duty Harley-Davidson pinion shaft bearing kit using a JIMS pinion bearing tool and it was time to slip the cases together with Yamabond on the case edge, while applying assembly lube on the pinion shaft. The case bolts were torqued to 18-22 ft. lb.

“Don’t forget the new oil pump O-ring when installing the high flow H-D pump,” Eric pointed out. Eric has an engine-building quirk. He continually turns the engine over, while rolling through the build process, and constantly tests for changes. “I want to catch anything that might bind early on,” Eric said. We actually ran into a small glitch while installing the cam plate.

But first, he installed the oil pump return gears, and then the separation washer and the spring, before the feed gear. He bolted the cam plate in place with ¼ -20 fasteners torqued to 120-inch- pounds. He used guide pins to help align the oil pump, and turned the engine over while tightening the pump so it would seat itself properly. He tightened two oil pump bolts, then removed the guide pins, and then tightened the other two Allens.

While aligning the cam drive gear dots, he installed the cams and used red Loctite on the drive gear Allen bolts, but used assembly lube on the washer for more accurate torque values and to prevent the bolt from galling against the washer surface for a false torque reading.

As we wrapped up the operation for the day, Eric installed the lifter with the oil holes facing the cam cover, then the guide pins, caskets and covers. No more lifter stools.

Day 3

Eric sub-leased a portion of his Signal Hill building to Branch O’Keefe, perhaps the best head porting business in California. I don’t want to put down any performance heads, but Jerry Branch, who is now about 82, built a helluva business around head performance.

Here’s a description of their heads from the Branch-O’Keefe site:

This is where is all began. Branch-O’Keefe is known throughout the industry for legendary cylinder head modification service. Our extensive reworking of stock Harley-Davidson cylinder heads begins with removal of the stock valve seats and guides. Next, the combustion chambers are heliarc welded to add additional aluminum alloy in the combustion chamber and around the valve seats for re-machining.

The valve seat pockets are then machined for larger nickel-chrome valve seats, and the combustion chamber is cut from the stock low compression rectangular shape to the legendary Branch “bathtub” chamber. After cutting the combustion chamber, new oversize valve seats and performance-quality valve guides are installed to tighter than stock tolerances.

The heads then advance to the porting room where the ports are fully hand-ported, blended and polished to Branch’s exacting specifications as proven on the dyno and flow bench. The head’s gasket surface is machined an additional 0.050-inch, which raises compression slightly. Finishing up, new oversize intake and exhaust valves (hard chrome stainless steel with stellite tips, polished face) are installed in bigger seats with a machined race-quality valve job and then hand-lapped. New seals and a high quality high-lift radius spring kit complete the installation.

The Branch O’Keefe head components are damn impressive from the titanium upper collars to the single oval wire spring with more travel and a larger diameter spring material. They have developed heads for JIMS big inch motors that produce 132 horsepower and ft-lb of torque, at an absolutely stock reliability level, even on a B motor. So natch, Eric had John O’Keefe and his master right-hand man, Paul go through his heads. Actually they used a formula they call the Dave Thew head. It’s a nickname for a performance formula. Dave beat everyone with these Branch O’Keefe head configuration. I will outline the different formulas next week.

We started the day installing S&S pistons with wrist pins first, since the oil rings pass over the wrist pin holes. Seems odd, but it’s the nature of the short-skirted piston. “Actually it allows for more skirt on stroker motors and does away with stroker plates,” Eric said. “This piston configuration will keep a stroker running longer.” The oil ring must be positioned with the dimple in the wrist pin area in a particular location to prevent rotation. The S&S pistons use four-piece oil rings with a removable ring land.

Eric installed the bottom compression ring so that the opening faced the exhaust port area. “No gaskets are used on the bottom of the cylinders,” Eric said, “just O-rings.” He compressed the rings carefully, lubed the inside of the freshly bored cylinder and slid the cylinder into place. Then Eric spun the motor over to check for binding. “I can’t wait to hear the D&D pipe.”

Eric started to install the heads using Cometic gaskets. The heads were torqued to Cometic specs and then he set to installing the rocker boxes and the fasteners, which were torqued to 22 foot-pounds. He started from the inside and worked out. Then he slipped in the S&S Quickee-Install intake pushrods for maximum valve opening. “I run premium S&S lifters with travel limiters,” Eric said. “They become solids at high RPMs.”

He tightened each pushrod until the valve slipped off the seat, and then let it bleed down, for about 10 minutes. He backed off the adjustment until he could spin each pushrod (one at a time). Then he backed off just one complete turn or six flats.

These shots were taken before John O’Keefe came up with a crazy notion to machine Twin Cam cylinder fins in a round configuration. Eric was knocked out by the procedure and pulled his barrels for the process.

In the next episode, Eric will slip the beautiful 106-inch Twin Cam into the stock frame, and we will discuss JIMS tools, while replacing the inner primary bearings, the slightly modified Dyna D&D pipe, and then and the new Rivera Primo clutch, the S&S G carb, and a new S&S high flow air cleaners.

Sources:

Bennett’s Performance

S&S

JIMS

Timbo’s ’64 FL Restoration (Part Two)

By Robin Technologies |

1964 was an interesting year for Harley. it was the last year of the 6-volt electrical system, and last year for the kick-start only. In 1965 they stepped up to 12-volt system and the first electric start and massive batteries started to appear. So let’s get started, I removed the primary, to my surprise it had a belt drive in it.

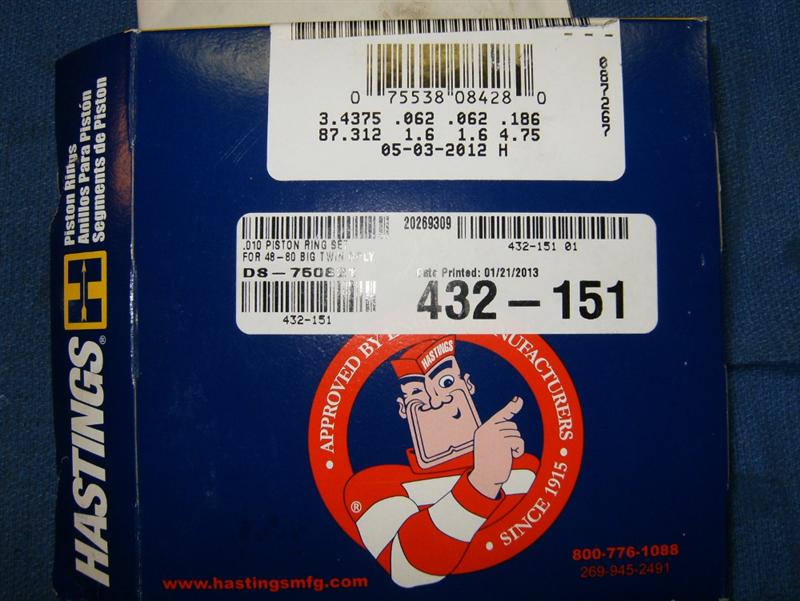

Someone wanted a step-up from the original chain drive, unfortunately it’s covered in oil that leaked from the main shaft seal and chain oiler that was never shut off. I might be able to save it with a healthy cleaning, we’ll talk about that later. After removing the primary drive and clutch, I thought the transmission would be a good place to start the restoration.

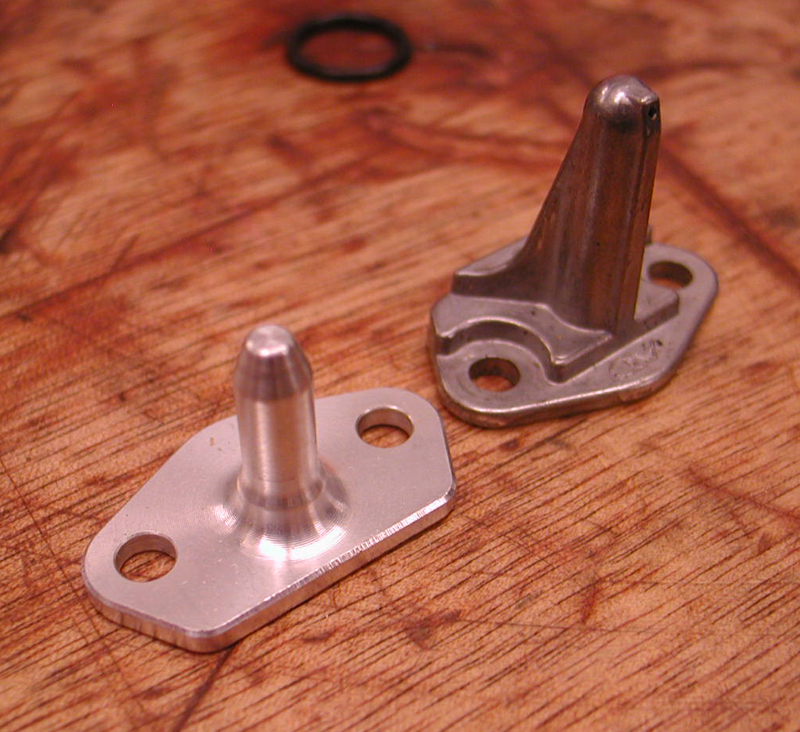

I did the research and found out all the parts I needed to rebuild the stock 4-speed transmission were available from J&P Cycle, and manufactured by JIMS. So off to the catalog I went. I ordered all the gaskets and seals I needed to rebuild it, except one, the main drive shaft seal (which was the worst one out of the bunch). According to the manual and other people I talked to, you need to invest $250 in the special tool from JIMS. It removes and installs that seal. However, I found an old friend (older than I) sorry Danny! LOL, who knew how to R&R the seal without the so called special tool, no big deal, according to him!

Be careful not to lose the gear shaft key for the sprocket. Also, there’s a small keeper key (looks like a flat L). It holds the sprocket far enough away from the seal, so it doesn’t ride on the seal. Keep it just in case. I later found out the new seal came with the keeper, but it’s better safe than sorry, if ya know what I mean.

There are some measurements you can take with feeler gauges for the shifter forks and spacers, refer to the manual.

Also you can check the timing shifter notches for alignment after the cover has been removed, also in the manual.

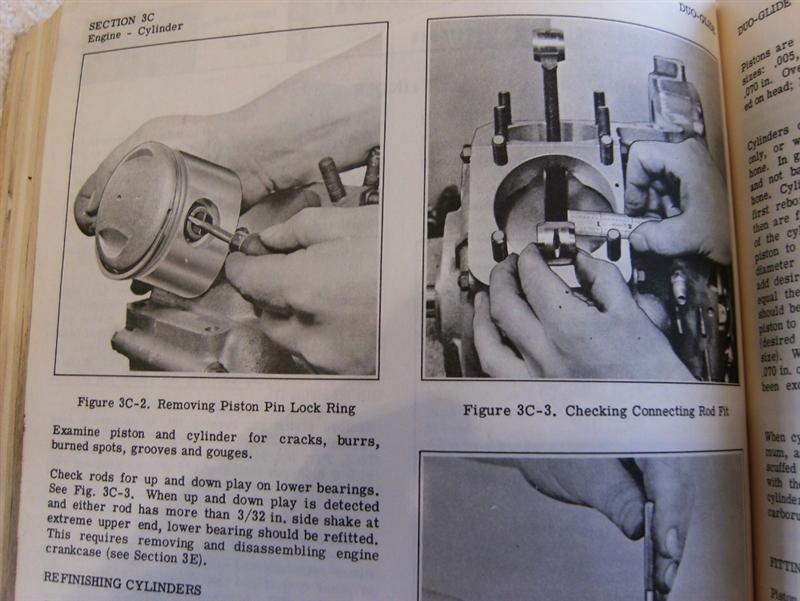

I actually ended up with two manuals, the original 1964 Harley service manual and a Clymer manual. Out of the two, I prefer the original service manual, it’s so easy to read and understand an idiot can follow it. Wait a minute! It’s also a good notion to pick up a parts manual for a variety of parts illustrations not found in service manuals.

For the serious rebuild the Wolfgang Panhead Restoration book, by Rick Schunk is an excellent guide. We were fortunate to have a low mileage transmission, and only a clean- up was required.

All the schematics are hand drawn in detail, very cool and definitely vintage. For the main shaft sprocket seal, I used the old school method my friend suggested, a slide hammer. Simply drill a couple of 5/32 holes in the seal, not too deep, about ¼-inch, screw in a sheet metal screw, and slam away!

It came out on the second slam of the hammer, YEAH! Installing the new one was just as simple, add a little Vaseline or WD40 to the outside of the seal and gently and evenly tap it in. I used a brass seal installer I had lying around, moving it back and forth on the seal so it doesn’t bind. Tap it down flush with the case, and your done. The JIMS tool insures that the seal is installed perfectly square into the case.

The rebuild kit came with all the gaskets and seals. There’s an O-ring seal in the kick-start shaft that rides between two brass bushings, be sure and replace it.

You can reach in with a dental pick or small screwdriver, and remove it without pounding out the bushings. The kit comes with new gasket for speedometer cable and neutral light indicator.

I polished up all the chrome it had and added a brass kick-start pedal, it looks great! Yeah, I know, not OEM pedal, but it looks cool and is pretty close to the era. I also ordered all new chrome case screws, the old ones were rusted, plus the chrome looks better anyway. I painted the inner timing cover and polished the out cap. You will find that almost all the transmission and engine cases are cadmium platted.

Lots of guys polish or chrome them, my customer wanted them to look as factory as possible. Here it is, the finished product. Not sure what I’ll tackle next, if you have any requests, let me know, I’ll be glad to accommodate. I’ll probably go right into the engine. That’s all for now, Tail Gunner out till next time.

Bikernet/Cycle Source Sweeps Build, Part 3, Sponsored by Xpress

By Robin Technologies |

Hang onto your asses. This is going to rock your boat, or your solo seat springs. We are building a bike just for you. That’s right. A Cycle Source or Bikernet reader will own this one-off custom at the end of this year. No, I’m not kidding.

This world-class team of builders, lead by Prince Najar, the vast and all-powerful organizer is headed-up by builder/designer Gary Maurer of Kustoms Inc, and Ron Harris of Chop Docs. We have the Texas Bike Works frame, the magnificent Crazy Horse 100-inch engine, and Jules, of Kustoms Inc. hand-made an oil tank. This issue we welcomed another state of the chrome-arts team into the fray, 3Guyz, a manufacturing shop capable of anything. They work out of a former aerospace manufacturing facility in Hillsboro, Oregon. Their mantra is as follows: Providing specialized customizing and performance solutions for American V-Twin and sport motorcycles, Smart cars, and industrial clients.

I spoke to Andy, one of the guys, who introduced me to the boss, Bob, and the other guy, John. Around 2004, they needed a springer, and although they were big fans of Sugar Bear, they decided it was time to manufacturer their own.

“We started by building a dozen all stainless springers,” Andy said. “We still have a few.” Then they discovered the need to build springers for builders who sought flexible units for various finishes. Each springer is custom-made for whatever application any builder needs. In this segment, we will reprint the 3Guyz tech on how to measure a roller for the perfect length springer. They also published a tech on tearing a 3Guyz springer down for finish work.

For more details about fork design and handling, take a few minutes to read through their “Fundamentals of Front Fork Geometry” in the 3Guyz.com tech section.

So here’s what Gary was faced with when the word came from Prince Najar, “3Guyz will make us a springer. Order it, will ya.”

Options:

Brake stay(s): Right, left, none or both (we position them, and provide the correct bolt thread based on the brake system you choose). In this case, we are using Hawg Halters.

Handlebar mounts: Standard is ½-inch through holes on 3-1/2-inch centers in the top tree for solid mounting, designed to use any stock Harley risers. You can add bushing mounts, or larger holes for custom handlebar controls. Or a springer can be ordered without holes for risers. Their springers are available wide or narrow.

Axle diameter: Standard is ¾-inch. You can choose to have us provide a 5/8-inch axle for spool wheels if you prefer.

Fork Stops: Standard is external pin stops in the lower tree based on our bearing cup stop set. You can choose to add in our cup and bearing kit, have us provide the internal stop kit, or specify internal stops by providing the manufacturer details about the stop kit.

Brakes: You can provide the distance from the axle to the brake anchor link point on your brake kit, and we will place the brake anchor where necessary to match it. We can also provide a wide selection of brakes from aftermarket suppliers and pre-fit them to your fork.

Fenders: Left fender mounts, off these springers are available to allow adding the fender of your choice (there are too many possibilities to list here).

How to Measure Your Frame for a Springer Front End Build

To build a springer front end specifically to match your frame, we need a few simple dimensions and facts.

All the directions and examples here are based on the fact that your frame uses a 1-inch neck similar to a big twin H-D. If not, you can use this example, but you will have to give us additional information on the length, inside dimension and outside dimension of your neck to determine, if our system will work with your frame.

To start, set your frame up on a riser (blocks, or a jack) to set it at ride height. That is, where you want it to be when the bike is fully finished, and running down the road. It is best to do this with the rear wheel (in this case Ride Wright wheels) and tire (Metzler) installed to allow you to set the lower frame tubes level with the ground, or slightly raised, as some designs prefer.

Mock-up-frame-height. In this example, we have mounted the rear wheel in the frame, and used a frame jack to set the “attitude” of the frame stance. This step is important, as changes to the angle of the lower tubes to the ground can change the neck height, and neck angle as the frame pitches upward.

We typically use a digital inclinometer to establish the neck angle for our calculations to measure the angle within one tenth of a degree. We do not expect everyone to have one of these. We’ll show you a few other ways to get the neck angle damn accurate with common tools

To measure the neck angle relative to the table, we need to zero the device. In the photo above, you can see that we have used a long straightedge set on top of the table surface to average the table surface. This is important because these lift tables are not flat, and we need to establish a flat average surface plane to measure from.

As you can see, there was an error here. Our floor is sorta flat here as well. Most garage floors at home slope toward the door, and can induce more error. If you are using a lift in your garage, try to set the table across the natural slope of the floor to eliminate that possibility. Most garage floors are somewhat flat side-to-side.

After the gauge is set, simply set the gauge across the top of the neck as shown.

Keep in mind that:

1.The better these measurements are, the more accurately the front end can be built.

2. There are other ways to do this, but this is how we do it.

3. The smaller the neck angle, the less effect small errors have on the length of the fork

Let’s take a look at other ways to measure the angle. A machinist protractor is very inexpensive, and can be used as shown.

Keep in mind here that as we use a level to determine the angle, you must use the same technique on the table to subtract (or add) the correction angle into the measurement for a relative angle.

Another tool to use like this is available at lots of tool stores, and is pretty easy on the wallet. We see it in use in this shot.

Now that we have the neck angle, we need to know how far from the ground the neck bearing is.

Measure from the centerline of the lower neck bearing race (Bearing IN PLACE) directly to the table as shown.

It’s important to measure the lower edge of the bearing in the race, along the centerline of the neck axis.

This one measures 32 and 3/8-inch from the table surface. Try to get within 1/16-inch here.

This allows us to calculate the length of the fork, as long as we know the tire size, type, and brand you will be using. We have a table of “loaded” radius dimensions for most major tire types we can use to determine the distance from the table to the front axle.

With this information, we will build you a springer to fit in the space required, and we will pre-load the springer so that it will settle to this height when it is fully loaded with the bike and average rider weight.

We also use this geometry to select the correct size rocker length and tree selection to provide you with the best steering trail for a safe and smooth ride.

Gary Maurer has been building bikes for years, so I’m sure he has a formula for figuring the springer length or he can follow the instructions here. So, the other crucial variables at this point were the dimensions of the wheels and tires.

I reached out to Ride Wright wheels in Anaheim, California. They manufacture custom wheels, rotors, and pulleys for Harley-Davidson, American Classic, custom chopper and import motorcycles.

“We strive to be your one-stop source for aftermarket custom wheels and tire needs with the hottest styles and various sizes, including super wide or tall rims.”

They make straight, cross, and cross-radial (overlapping) lacing patterns with smooth and diamond cut wire and spoke wheels in 40, 50, Fat 50, 60, 80 and 120 spoke-count styles. They build their own high-polished stainless spokes in diamond cut, twisted, jeweled and blade styles. Finishes include custom colors, powder coating, chrome, and polished hubs and rims.

They also manufacturer steel and aluminum rims. Their soft-lip aluminum rims have no step and are thick enough for engraving or machining.

This is damn exciting, the way this putt is coming together right before our eyes. We now have a complete roller, and soon the sheet metal fabrication will begin under the guidance of Gary, Jules, and Ron. Hang on for the next chapter. And remember you can win this one-off custom chop. Just subscribe to Cycle Source or Bandit’s Cantina on Bikernet.com. Or just fill out the application and keep your money. No purchase is required, but don’t tell the other guy.

–Bandit

Xpress

http://mysmartcup.com/

Crazy Horse

http://www.crazyhorsemotorcycles.com/

Texas Bike Works

www.TexasBikeWorks.com

Kustoms Inc.

Chop Docs

Accel

Accel-ignition.com

Fab Kevin

.jpg)

D&D Exhaust

http://www.danddexhaust.com/

Wire Plus

http://www.wire-plus.com/

Barnett

Barnettclutches.com

Rocking K Custom Leathers

Ride Wright Wheels

Bell

Metzeler Tires

ACORN NUTS MEET THE MUDFLAP GIRL

By Robin Technologies |

|

||

Timbo’s ’64FL Panhead Part 3, Engine

By Robin Technologies |

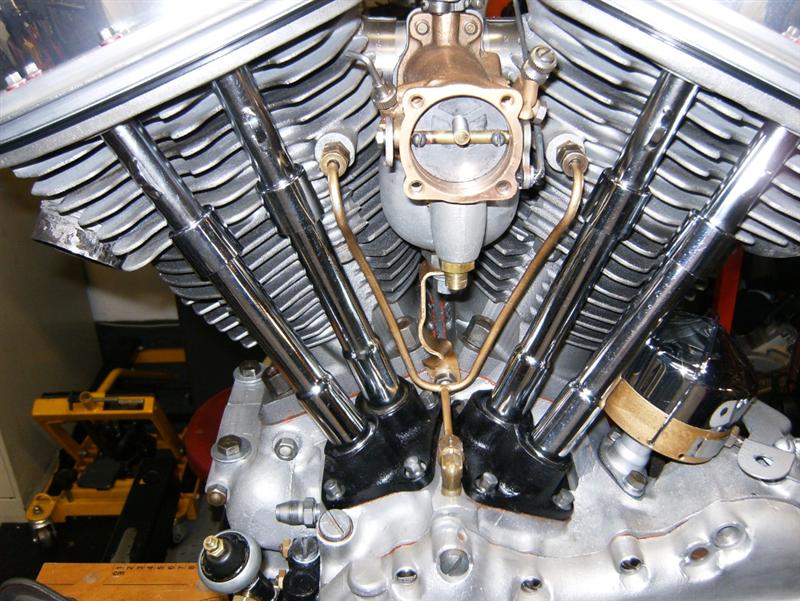

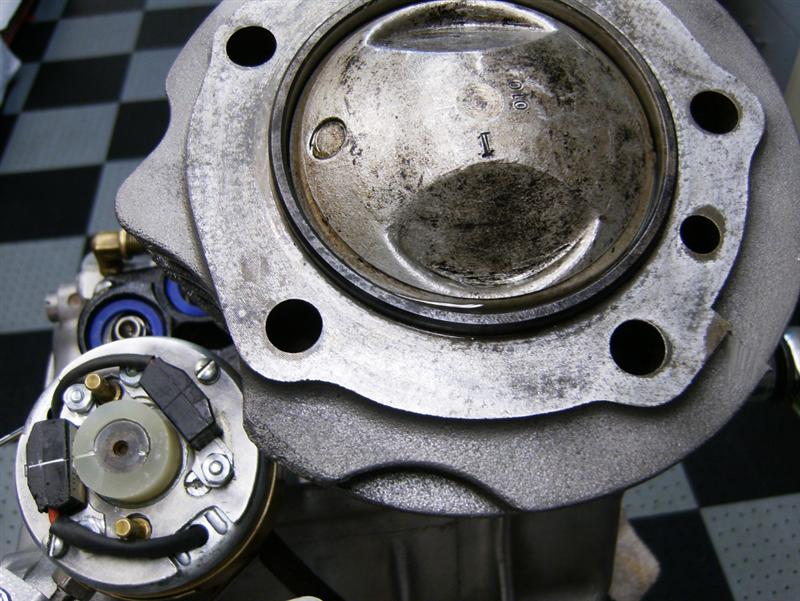

Tear down was straight forward, first I removed the carburetor, followed by the oil pump, gear drive housing, push rods, tappet blocks, rocker covers, heads and barrels. After the barrels have been removed, place a couple of shop towels around the connecting rods to keep debris from falling into the crankcase.

I carefully cleaned all old gasket material from all the mounting surfaces. I ended up using razor blades and plastic scrapers. Be careful not to gouge any mating surfaces as you scrap. Any abrasion could create a leak if the gouge is deep enough.

You can follow the generator instructions in the manual. It’s extensive and takes patience, but not overwhelming. I just hope it works, as a new costs around $400! Ouch! I also found “Rene “at National Starter in Lancaster, California. He Put the 6v through its paces to make sure we have a strong working unit, Thanks Rene!! The old mechanical voltage regulator was replaced with a new solid state unit and the OEM dual point circuit breaker was replaced with a state-of-the-art electronic dual contact unit from Quick Start 2000.

Ed from Quick Start custom builds electronic circuit breakers specifically for vintage motorcycles, and he spilled a wealth of knowledge, always willing to help in any way he can, yea ED!!!!

Rebuilding the oil pump was a simple task, you can get the complete kit from J&P Cycle. The gear case cover was removed and the timing marks were checked for alignment.

I removed the tappet blocks and tappets, cleaned them and miced them to see if they are within tolerance, they are. Be careful when reinstalling the tappets, they need to go in the same position (same hole) they came out of, with the oil passages near the rollers pointing inward (refer to manual). Failing to do this will cause the engine to seize, and we don’t need that.

Timbo wanted the barrels to be blonde, so I had them bead blasted to remove the black Bar-B-Q paint someone had put on. In my opinion, they look way better blonde. As far as the heat transfer, I don’t think it makes much difference. Most Harley engines of today are blonde, the black is a cosmetic option. I have built aircraft engines for 20 years, and almost all are bare metal cooling fins. I coated the bare metal with clear 1500 degree heat paint, just to make sure they don’t rust up on me.

We can argue the “black heat dissipation thing” at a later date! For the barrels and heads, they suggest you purchase a special wrench to ease installation and removal. I found a little patience and a standard 9/16 and 5/8 box end wrench and 12-pt. deep socket worked just fine for removing the barrel and head bolts. I was fortunate to have the original manual, a Clymer manual and a cool restoration book sent to me from Bandit.

New rings installed along with the cylinders cleaned and honed. The heads looked really nice, no gunk had built up yet and the valves were lapped just to make sure. I also cleaned out all the oil passages, don’t want any debris mucking things up!!

At last, the engine is complete for now. Since beginning this article, I have already installed the engine and trans in the frame, another article on the frame will follow soon.

Tail Gunner out for now!

Doug Coffey’s RetroMod Panhead Part 1

By Robin Technologies |

Other than the missing sidecar sidecar loops, it has a strong resemblance to a 1957 straight leg rigid frame. Exactly what I wanted.

Doug Coffey’s RetroMod Panhead Part 2

By Robin Technologies |

1964 Pan Head part 4 (frame)

By Robin Technologies |

Oil tank and lines were next on my agenda. I opted for a more modern spin on oil filter adapter, it looks nice and makes oil changes a snap. I kept the original oil filter that was polished just in case the owner wants to go all original some day.

The front forks have been completely rebuilt with all new modern seals, I had them polished also, looks nice! My customer decided he wanted a old school look on the wheels like they did in the ’30s and ’40s, so we blacked out the spokes and hubs leaving the star bearing plates and lug bolts the original parkerized coating.

Just about everything that is aluminum was polished like chrome. We kept to the OEM look on the primary and oil tank, which was black with touches of chrome.

As for the clutch shift linkage (mouse trap), it also was completely gone through and restored, polished and looks like new. I did find out why they call it a mouse trap! Got my Fuckin’! finger snapped twice while trying to adjust it, IT HURT BAD!

The brakes have all new shoes, lines and fittings. Front brake is mechanical and rear is hydraulic, all juiced, adjusted and ready to go. Tires we picked are replicas of the day. They are Shinko reproduction white walls. Not the best, not the worst, but fit the budget just right. They have all new tubes, rim belts and have been balanced and trued by me.

The new exhaust went on comfortably with new head clamps. We kept the original muffler. It was salvageable. All the footboards have been rebuilt with new rubber and rivets and foot controls were installed.

The original generator in chapter 3, was a no go, it had a bad armature and wasn’t cost effective for a rewind. So I ordered (cust. request) a new 6v generator with built in voltage regulator, it too looks very nice. Just a quick rundown, the electric system although all 6v, has all new solid state components i.e. electronic dual breaker distributor with a solid state voltage regulator, no mechanical parts.

The electrical has all been installed and wiring is complete less the head light and tail light. Both electrical junction boxes have been rebuilt with new insulators and wiring harness.

There’s a lot of little things like the $5 chrome chain guard I found at the swap meet and some odds and ends I also found in good condition cheap, at the swap meet. You can see them in the photo’s if you look hard. The steering head lock was a nightmare. It took me months to track one down on eBay. Shortly after I purchased the one on eBay, JP Cycles informed me that they finally had one in stock, go figure!

Mudflap Girl FXRs, part 11: The First Road Test

By Bandit |

Mudflap Girl, chapter 10: http://www.bikernet.com/pages/Mudflap_Girl_FXRs_Part_10_Suspension_Tuning_and_Le_Pera_Seat.aspx

I can’t make it to Sturgis this year. We are focused Bonneville builds, like mad starving dogs, and the two events are only separated by two weeks. Ray is tuning and I still don’t have an engine, but we’ll cover that later. The engine could be running today, in Richmond, Virginia, at Departure Bike Works.

Okay, so what’s a poor bastard to do, when he planned to make the run to the Badlands with his brother Hamsters? They ride out from the West Coast every year. Some of the members, including Arlen Ness are in their 70s and riding custom Victory bikes. Some rode from Spearfish, South Dakota, out to Mammoth Lakes, California, to ride back to the Badlands with their brothers. So, what’s the least I could do? Meet them at their first stop in Mammoth, just east of Yosemite?

The good doctor has owned several motorcycles, including a 1934 VL I helped get running, but one motorcycle stuck with him, a 1989 FLH. He had clocked over 200,000 miles when he decided to rebuild it. Bennett’s Performance handled the semi-stock Harley engine (the rebuild was covered on Bikernet). With a couple of thousand miles on his rebuild, and 50 on mine, (another 80-inch semi-stock Harley engine, assembled by S&S, with headwork by Branch O’Keefe), we rolled out of Los Angeles.

About 15 million folks know rolling out of Los Angeles is the biggest challenge to any weekend excursion to someplace less congested. It’s amazing, like no-man’s land at the front of any war zone. Just try to slip out of Los Angeles on a Friday. Try to peel by noon or before. If you don’t you could be faced with serious bumper-to-bumper malady, or a lane-splitting conundrum. We recently published a report about splitting lanes and the benefits. They actually made a case for increased safety in areas supporting lane-splitting.

I’ll make one case for the freedom to split lanes, maybe two. Well actually, the published study pointed out the benefits of keeping motorcycles moving during high-congestion back-ups. My point included any rider’s sense of alertness. When splitting lanes the rider’s acute awareness is on high alert. Even while putting past a myriad of parked cars, a brother never knows what could blink, so his senses are hot wired. He or she is aware of anything that moves, from a slight wheel shift, to a nod, or a turned head.

So, I split lanes as soon as I hit the 405 freeway, off the 110, the oldest freeway in the US. It runs directly into the heart of Los Angeles, downtown, from my digs in the Port of Los Angeles. As I pulled out of Wilmington, two concerns stirred my humble sense of motorcycling comfort. First, I discovered my rear chain smacking the Spitfire hand made oil tank. There was always a bothersome noise bugging me, and I finally discovered the treacherous origin, the rear left corner of the FXR-styled, rubber-mounted oil bag.

Fortunately, the Spitfire team had welded a threaded bung into the corner, and a tab off the frame. I ran across the problem during assembly and removed the tab for more clearance, but evidently not enough. So the night before the run, I removed the chain, cleaned the threads with a tap, and made a countersunk Teflon bumper to protect the tank, but would it last? Or would the chain disintegrate my protective barrier, cut a hole in my oil tank in the middle of the Mojave Desert, dump all my oil onto the highway, seize up the engine, and leave me to be tarantula bait, after I baked under the 107-degree blistering desert sun?

I also made one final adjustment to my Wire Plus speedometer sensor stuffed into the JIMS Screamin’ Eagle over-drive 6-speed transmission. I had tried everything. I was at a strange juncture. It’s been so long not working, if it worked I would have been shocked. As I pulled away from the headquarters, I wasn’t disappointed. It still didn’t work. Now, I have another idea. I didn’t connect the wire from the sensor to the speedo wire directly, but to a connection board. Maybe a direct connection would be the trick.

Somewhere in the sizzling desert, with the afternoon sun baking my feeble skull, the notion of this road test article was spawned. The Mudflap Girl FXR contained only 50 break-in miles so far; this 700-mile jaunt would be the iron test. I had followed the Eddie Trotter break-in regime, almost to the tee. With each longer and longer ride, I returned to the headquarters to make corrections, repairs, and adjustments. It was time for the acid test, a long road into one of the hottest regions in Central California, a total round trip of perhaps 700 miles in 2.5 days. That’s a big deal for this old guy.

There I was, splitting lanes across the LA airport toward Santa Monica and the good doctor’s office, where he was leaning over his knockout secretary and adjusting a tall tattooed redhead. Tough job. Sticking around his office near the coast, with a bottle of something, would’ve made my weekend.

Oh, one more concern disturbed my peace of mind. I started to write peach. I was still with the girls in the office. I hand-made the two mounts holding the single RockShox to the girder. My mind whirled with 80mph impact, a bottoming out shock, and the stress on the mounts. Would they last or toss me into the fast lane of a crowded Los Angeles freeway? Ah, for the days when we would build a bike, smoke a joint, down a shot of whiskey and ride some half-wired together chopper across town at breakneck speeds to her house. Hell, we felt so good, it didn’t matter if we made it our not.

While parked at the good doctor’s office, I inspected my Teflon pad. It was sliced severely, in just 40 miles, but the next 40 or 100 would finalize the experiment. My shock mounts hung tough, but what about the next 100 miles? We gassed up and peeled out onto a crammed 10 Santa Monica freeway. Splitting lanes and dodging merging traffic we weaved onto the 405 Freeway. It peels over the notorious Sepulveda Pass, into the San Fernando Valley, and beyond toward the 5 Golden State, high-speed direct link from Los Angeles to the bay area and San Francisco.

We just needed to cut across the 101, to the 5 for a five-mile stretch, and then off on the 14 toward the Mojave mile airport landing strip and land speed trials location. I felt every bump and groove in the crappy road as I leaned into the fast lane and poured the coals to this 80-inch beast. It ran sweet. I set up the dual-fire, Compu-Fire ignition according to instructions, and installed the Trock modified CV carb, but never adjusted any aspect of it, except the idle.

The week before we peeled out I rode to Bennett’s Performance and Eric popped the cap off the air fuel adjustment behind the float bowl, and adjusted it—it was too lean. Trock removed the cap, so the adjustment screw was operational. I rode the bike, noticed an intermittent cough, and called Eric. He recommended backing out the needle one-quarter turn. She seemed happy, and in Mojave we refueled and checked our mileage against Christian’s trip meter. We had covered 90 miles and I reloaded with 1.82 gallons for 49.45 mpg. It pulled well in any gear, even in sixth gear. The JIMS Screamin’ Eagle Overdrive transmission shifted like butter and never missed finding neutral. I geared it slightly high for a 6-speed with a 23-tooth trans sprocket and 51 on the rear wheel.

So far, we flew along big wide freeways through the Soledad Pass, Palmdale, Lancaster, and then into Rosamond. At over 90 degrees, the freeway started to die and turn into a two-laner along-side the Pacific Crest National Trail leading into the Sequoia National Forest. It looked sorta bleak and hot to me, as I pondered the welds that held my chopped Spitfire bars together. So far, the riding position was a dream. My legs were stretched out nicely. I could move around on the very comfortable gel-impregnated Saddlemen seat with the spine relaxing channel, and just a touch of lumbar support. The bike handled well, as I adjusted to the long bike vibe.

Another rambling rural 50 miles in the desert with only rolling hills in the distance, and the 14 Highway disappeared to be replaced with the well-kept Highway 395 in Indian Wells Valley. We passed more deserted truck stops, than active ones. They were extreme sun-dried out buildings. Chipped paint was sandblasted by desert winds, and busted windows gave the dilapidated structures, gradually turning to dust a war zone appearance. I set the bike up to be a chopper for the long road, with rubber H-D pegs, old styled thick rubber Knucklehead grips, and Custom Cycle Engineering rubber-mounted traditional dogbone risers. Since the drive train was rubber-mounted, it all worked to minimize vibration.

We followed one billboard to an old gas station turned into jerky sales headquarters. It bragged “Good jerky.” It was actually so-so, and small packages were priced at nine clams. I wanted to support their sticker-scattered cause. The smiling Hispanic broad behind the counter gave me the okay to plant a Bikernet sticker on the building, yet I couldn’t cough up nine bucks, plus tax for a bag of so-so jerky. We peeled out.

Just a handful of small towns peppered the highway with reduced speed signs, some as slow as 25 mph, perhaps a fund-raising effort. We rolled into Lone Pine and the Dow Hotel, which was packed with tourists and bikers heading to Sturgis. The Dow, built in 1923, was specifically constructed to house movie crews, since a large number of westerns were shot in the region. What a roll of the dice, but it paid off. We topped off and compared notes this time. We had sliced through 111 miles and I took 2.3 gallons, for 48.3 mpg. The doctor grabbed more fuel between stops, so he crossed 38 miles and took 1.2 gallons for 31.6 mpg. He was disappointed, and we discussed options for the future.

The good doctor noticed some drops of oil on the pavement next to my bike. My oil cap isn’t correct for the screw-in bag bung, so I found a press-in rubber cap, with a small dipstick. It worked, but loosely, and a small amount of oil seeped onto the roof of the Spirfire steel oil bag, then some trickled down the right side, onto the frame and dripped onto the pavement. I pressed the oil cap deeper into place and check the oil level, and then it dawned on me. I noticed a softening in my rear GMA brake action. That was the cause.

[page break]

I checked the Teflon pad, and it didn’t indicate any more chain damage, plus the tank was well clear of the carved edge. It appeared very secure, and my shock mount held fast. Vibration was minimal, and at every stop, folks confronted me about the Mudflap girl bike, the traditional chopper appearance, and almost every onlooker said, “Is it a rigid?”

The next morning, we faced just 99 miles for our meeting with the evil Hamsters at the Westin lodge in the heart of Mammoth lakes. The roads were perfect and our 80-inch Evos purred as the elevation increased from sea level to 4000 feet, and we were expecting another 4000 thousand and more pine trees as we cut a dusty trail toward the Sierra Nevada Mountain Range, just east of Yosemite. We stopped in picturesque Bishop for breakfast, but the two hot spots were jammed. We strolled into Whiskey Junction without a problem, then rode the remaining 40 miles to the Mammoth cut-off. I was expecting winding, twisting mountain roads into the mountain/sky resort community, but it was virtually a straight shot. My memory reminded me of a similar stop the year I hit a deer inWyoming.

We didn’t pop for the high-dollar rooms, but stayed down the street at the Sierra Motel, where the doctor pointed out a concern with his front wheel. We rode up the street to hang with the Hamsters as they rolled in as early as noon. Some rode in from Spearfish, but the Bay Area contingent, including Arlen Ness chose to fight traffic in slow lanes through Yosemite National Park. They weren’t scheduled to arrive until the early evening, so we returned to our digs to take a look at his front wheel. Under the backdoor hotel overhang, we found a massive cinder block, jacked up his FLH and removed the front axle. One of the bearings demonstrated serious damage and we attempted to remove it with the help of the Hawaiian biker handyman.

We easily had enough tools between my Bandit’s bedroll and the doctor’s tool bag. Concern grew as we discussed our issue with other riders, and Ted Sands, from Performance Machine. “Did you powder coat the wheel?” Christian scored a couple of late model Twin Cam, 1-inch axle mag wheels, powder coated them, and replaced the bearings with ¾-inch axle jobs, but there was some question about the internal spacer. The spacer needed to be solid against the inside bearing race, and that didn’t seem to be the case. The left bearing demonstrated serious wear. We started to make calls.

The Mudflap Girl bike handled the roads to Mammoth extremely well, although we are hoping to step up and buy another RockShox with at least 2-inches of play and a 250-pound rated spring for testing in the future. I’m sure with the correct resources, we can make this girder ride like a Cadillac. I ran into one problem with the Mudflap girl. The left stock H-D foot peg with massive rubber padding for comfort, wanted to slip off the stem and depart. I thought this bastard wouldn’t budge, but I continually fought it.

We called for local bikes shops, but it was Saturday night and resources were limited. Christian made a run on my FXR to an auto parts and bought a jug of bearing grease, a spray can for chain-styled foam lube, and a small container of Buffalo-snot glue for my peg. I actually needed rubber cement, but gave it a shot.

“The FXR Chopper is one great looking scooter, with just the right stance to have attitude, without being obnoxious,” said the Doctor. “Everyone twists their neck when she goes by.

We operated as best we could on the doctor’s wheel but could not remove the bearing to correct the inner spacer problem. We packed that bastard full of grease and called for a U-Haul truck rental in Bishop for the next morning. The final question: Could, would, should the good doctor risk riding his Bessie down the hill? We confirmed with U-Haul; the regional office would open at 7:00 a.m. The Bishop franchise opened at 8:00 a.m., and a 14- foot box truck was available with a ramp. We would need to score a batch of tie-downs.

We returned to the Westin to hang with our brothers, Buckshot, a Bikernet and Thunder Press contributor, and Marilyn Stemp, the editor of Iron Works. That’s when Ted Sands told us about the drawbacks of powder-coating the interior of late model hubs and the impact on bearing spacers—bad news. I rode the FLH, and it rattled like marbles in an empty tin can, but I didn’t sense any grinding in the bearings. I didn’t want to make a recommendation. This had to be his call. Then I mentioned the 40-mile distance to Bishop. He was thinking 100 miles to Lone Pine.

By the way, we gassed in Mammoth for another 98 mile run. My bike was feeling the pain of reduced oxygen at 8,000 feet, and the night would drop to 41 degrees, but she still ran well. I struggled to squeeze the nozzle into my tank and loaded it with 2.5 gallons (39.2 mpg), and the doctor refueled with 3.2 gallons (30 mpg). He will look into a jetting change for his S&S carb.

As we hit the hay, the doctor decided to attempt the slow ride to Bishop. We set the alarm for 6:30 and tried to sleep.

The weather was amazing, just a tad cool in the morning as the sun slipped between pine needles to warm the streets. We packed and rolled down the hill to the first coffee shop. We were gassed and ready for the 40-mile delicate, risky ride to Bishop, a town of 5,000 along 395 just below Mount Whitney, the highest mountain in the continental United States. We were so focused on surviving the Bishop run, we didn’t think about the cool breeze, my wandering peg rubber, or any distraction. I’m sure Christian was as tense as an over-tightened drive chain as we rolled serenely down the mountainside onto 395 south at 45 mph.

“Going 40 miles down the hill towards Bishop was a bit nerve wrecking, since the bearings were grinding and clackering like marbles in a bag being tossed on the ground!” Said the doctor.

The good doctor rode almost 20 miles, his hands, like vice-grips on his bars waiting for the bearings to scream and spit from their housing. The hefty front mag would wobble, then lock against the twin Performance Machine 4-piston front brakes and scream for relief, maybe locking up and tossing the doctor and his gear in the weeds. I asked him to ride on the right for easy access off the road, just in case.

“But after about 20 miles the sounds and noises started to be less and less,” said the doctor. “Once we got to Bishop it had subsided 80%!!!!!”

We arrived right on time, and spotted a women in the U-Haul yard. “They don’t open until 11:00.” Her husband arrived and confirmed the bad news. Disillusioned, we rumbled into town for a hearty breakfast at Jack’s and made a number of phone calls. If we could make it to Mojave, we could find another U-Haul, but then we would only be 100 miles from home. The Doctor could ask his girl to meet us there with a trailer. He called U-Haul, bitched and sought alternatives. None were forthcoming.

We said, “Fuck it,” and kept rolling. With each 50 miles, his confidence grew, but we remained at a mild pace of 60 mph, them 65. I finally got fed up with my spinning peg rubber and pulled off the side of the road and strapped it down with tie-wraps, pulling them damn tight.

“Do you want to cinch them down with a pair of pliers?” said the good doctor.

“Nah,” I responded. “We’re good to go.”

Yeah right. The sonuvabitch still squirmed and tried to escape. At the final refueling stop in Mojave, I broke out the pliers and pulled those tie-wraps as hard as I could. The bastard never moved again.

The doctor, comfortable with his FLH, resigned himself to flying into LA by himself. I would cut off at the 210 and dodge the rough, jagged, concrete 405, heading directly into one of the most congested intersections and construction zones in Los Angeles, the 101 junction, over the Sepulveda Pass to the 10 Santa Monica interchange. I could fly into the city on the foothill freeway against the San Gabriel Mountains into Glendale, cut south on the Glendale freeway for just 10 miles and pick up the 5 for one mile before I jumped onto the 110 south directly to my door through downtown Los Angeles.

As I peeled off the 5 at the 210, Christian gave me a final thumbs up and rolled into congestion for just another couple of miles, then cut off at the 405. It was just about 3:00, the bewitching hour, before a city of half-drunk yahoos, talking on cell phones and playing grab-ass with their girlfriends, headed home from barbecues, weekend camping beer-soaked outings, cantinas, bars, ballgames, you name it. This is the most notorious crew of inexperienced drivers, on unfamiliar freeways, buzzed, and distracted, heading home after too much fun. This group of millions, in tin overseas boxes and SUVs, with stereos blasting, is in contrast to commuter traffic, made up of professional, daily migrants, who know every inch of their incessant trips back and forth to work.

Both Christian and I have ridden LA freeways for over 35 years. We both rolled into our respective digs within 20 minutes of each other and checked in. Within an hour and after my first Jack on the rocks, I wrote some compliments and foreword thinking thoughts to Paul Cavallo, the Spitfire master, and he immediately responded:

“Hey brother, good to hear from you. Glad you had a great ride,” Paul wrote. “I have you covered on the oil cap. I just finished up a re-design on the girder trees that eliminates the shoulder bolts. I will update yours to the new gear.

“Bill Dodge rode his out from Kentucky for Born Free, and loved the ride, but after a 5,600 mile round trip, those little thrust washers wore thin. I doubled the strength of all of the pivot components, and machined pivot pins into the trees, and cross bars. I even designed a retro kit for all of the existing front ends.”

We discussed RockShox with increased travel, and I also mention raked trees for better cornering. The more you rake a bike, the more it wants to go straight, which hinders cornering. Bikers generally love to corner, and I discovered, with my blue flame that even a chopper can corner with adjusted frame geometry.

“When I update your front end, I will give you 3, and 6-degree links for it,” said Paul in his response. “The girder is so easy to change the rake on.”

There you have it. The first 700-mile distance test of our Mudflap Girl FXR. Scooter Tramp Scotty is right on: Evos Rule and Choppers never die.

Spitfire

D&D Exhaust

Biker’s Choice

JIMS Machine

MetalSport

BDL/GMA

Wire Plus

Branch O’Keefe

Bennett’s Performance

Custom Cycle Engineering

Saddlemen

Progressive Suspension