by Todd Halterman from https://www.autoevolution.com

Hub-center steering is one of several different types of front-end suspension and steering mechanisms used in motorcycles and cargo bicycles. It is essentially a mechanism that uses steering pivot points inside the wheel hub rather than a geometry that places the wheel in a headstock like the traditional motorcycle layout.

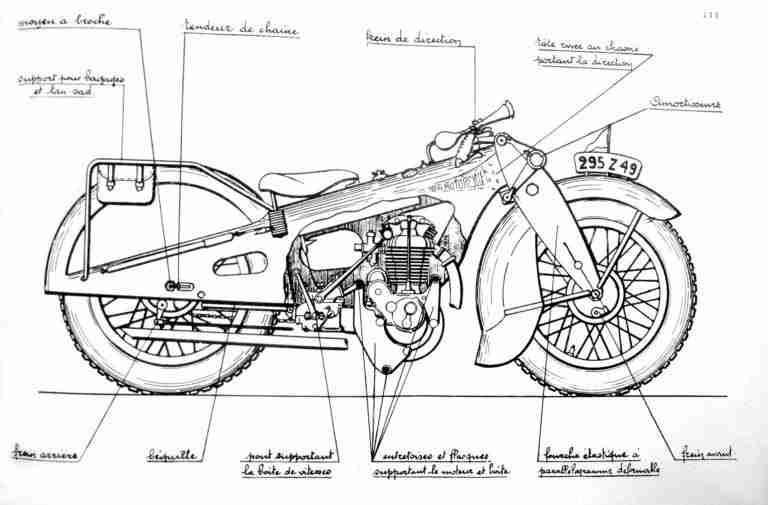

Perhaps the most venerable example of the idea came in the form of the 1930 Majestic. This Georges Roy design used a novel pressed-steel monocoque chassis, and it incorporated an automotive-type chassis with hub-center steering. Other bikes had already used the configuration in such machines as the Ner-A-Car and the Zenith Auto-Bi, but the Majestic made it lovely to behold.

Another bike, the Vyrus 984 C3 2V Razzetto, was one such motorcycle that used hub-center geometry.

Vyrus is a small Italian motorcycle manufacturer based in Coriano, Italy, and their bikes such as the “Tesi” – Thesis in Italian – had their designs originate from a university engineering project linked to the motorcycle legend Massimo Tamburini. The Tesi, and the Vyrus 984, were instantly identifiable by their use of their hub-center steering front suspension and steering arrangement.

Those fabulously expensive bespoke motorcycles have been called “functional works of art,” and they look a bit like something you might see in a video game.

In hub-centered bikes, the front wheel is attached to a swingarm with a shock and an internal pivot point. Steering is achieved using those linkages to turn the wheel on a pivot point. Hub-center steering has been employed on motorcycles for more than a century, but the design, despite what some engineers say offers a distinct advantage, never took hold.

But the founder of Vyrus, Ascanio Rodorigo, once worked for Bimota as a race mechanic and engineer during the 1970s and his tenure there lasted until 1985. When Rodorigo finally left Bimota, he started his own company but partnered with Bimota on the hub-center-steered Tesi. He then went on to take the steering concept deeper and refined it for his own company’s motorcycles.

A Ducati dual spark bored out to 1,079cc and making 100hp L-twin provides the power for the 319 lbs (145 kg) Vyrus 984 bike, and it’s delivered to the road for via a six-speed transmission.

Now builders like Bryan Fuller of Fuller Moto, Revival Cycles, and others have built beautiful machines which harken back to the hub-centered glory days of the Majestic. Builders such as Stellan Egeland used a hopped-up 1200 boxer engine from a BMW HP2 Sport. He also added his own hub-center steering setup from ISR to a frame he made from a 2391 steel tube. The ISR kit is a thing to behold.

Revival’s ‘The Six,’ which features a ballsy Honda CBX motor, is another take on the hub-steer geometry. It was commissioned by museum owner and bike collector Bobby Haas for his Haas Moto Museum in Dallas and made by Revival’s Alan Stulberg and his crew.

Stulberg said the commission was aimed at paying homage to the Art Deco classic Majestic and added that he and the team became “obsessed with its design language and flow” since they first saw the bike at the Barber Museum.

Hub steering systems don’t dive as much under braking and hard cornering as do conventional telescopic fork setups. They push braking forces back into the chassis more efficiently rather than transferring immense bending forces to a pair of upright forks. The ride experience is exceptional as braking performance throughout corners is greatly enhanced.

It works like this: A wheel hub pitches back and forth on a central pivot and is supported by two large steering arms actuated by handlebars. The handlebars connect to the front steering and swingarm using complex linkages. A fixed arm connects a pull-and-push rod on either side of the hub-center to help steer the bike. The geometry also includes a second pair of static rods to ensure the axle stays level with the bike’s mass.

While hub steering has a number of clear advantages, its downfall is that it is considerably more expensive to manufacture and maintain and requires exceptionally experienced mechanics to tune and repair.

But it does look good, works more efficiently from an engineering standpoint, and directly addresses the most important factor in the motorcycling experience: braking.

The Majestic – Artistic Design from the 1920s

from https://www.odd-bike.com

While the engineering of the Majestic might have been relatively conventional, what was unprecedented was the styling, the hallmark of the Majestic to this day.

All the oily bits were fully enclosed under louvered panels, with partially enclosed fenders covering the wheels at both ends. The rider was completely isolated from the grime and muck of the running gear and powertrain, perched upon a sprung saddle and controlling the machine via levers and bars that poke through the all-encompassing body.

Presented in 1929, the prototype Majestic (which was reported as Roy’s personal machine) featured an air-cooled 1000cc longitudinal four-cylinder engine from a 1927-28 Cleveland 4-61. This would not remain for production, however.

While at least two Majestics were built with a 750cc JAP V-twin (arranged, like a much later Moto-Guzzi , with the Vee transverse and the heads poking through the bodywork) and records note that JAP singles, a Chaise Four, and at least one Gnome et Rhone flat twin were also employed, the majority of production machines coming out of Chartenay featured air-cooled Chaise engines.

These were overhead valve singles featuring unit two or three-speed gearboxes operated by hand-shift, available in 350cc and 500cc displacements. Distinctive for their single pushrod tube that resembles a bevel tower (but contains a pair of tightly-spaced parallel pushrods) and external bacon-slicer flywheel, these powerplants were a favourite of French manufacturers during the interwar period and were used by a variety of marques in lieu of producing their own engines.

The base price of the Majestic was 5200 Francs for a 350 with chain final drive; an extra 500 Francs netted you optional shaft drive.

An additional option that is rarely seen on surviving examples was a fine “craquelure” paint option that was applied by skilled artisans. It involves a process of deliberately screwing up the paint job in the most controlled and flawless way possible, applying a contrasting top coat over a base using incompatible paints that will cause the top coat to crack in a uniform fashion, something like a well-aged oil painting or antique piece of furniture.

The result is spectacular – and perhaps a bit tacky, giving the machine the appearance of a lizard skin handbag. (Maybe a later Rock Star would have loved to ride it as the “The Lizard King” ? )

The Majestic was impeccably stable at higher speeds compared to the other motorcycles of that era.

It was also agile and light footed in a way that similar machines, like the Ner-A-Car, were not.

The relatively low weight, around 350 pounds, carried with a very low centre of gravity made for tidy handling that was more than up to the meagre output offered by the powerplants.

Majestic was targeting a clientele that didn’t really exist: the gentlemanly rider who might desire a superior (read: expensive) machine as a stablemate to their elegant automobiles.

Georges Roy’s earlier 1927 brand called New Motorcycle was a far better barometer of things to come, predicting the style and design of machines that would emerge during the 1930s and beyond. The Majestic has far less impact and was more of a curiosity than predictor of trends to come.

Georges Roy’s brilliance as a designer is unquestionable, and deserves more praise than he ever earned during his lifetime.

Majestic is a little bit of elegance floating on the sea of staid machines that clutter up the history books.

Georges Roy was a French industrialist and engineer born in 1888 who achieved success in the textile business – specifically in knitting and sewing equipment. He was, however, an early adopter of motorcycling at the turn of the 20th Century – reportedly his first machine was a Werner, a Parisian machine that introduced the term “Motocyclette” in 1897.