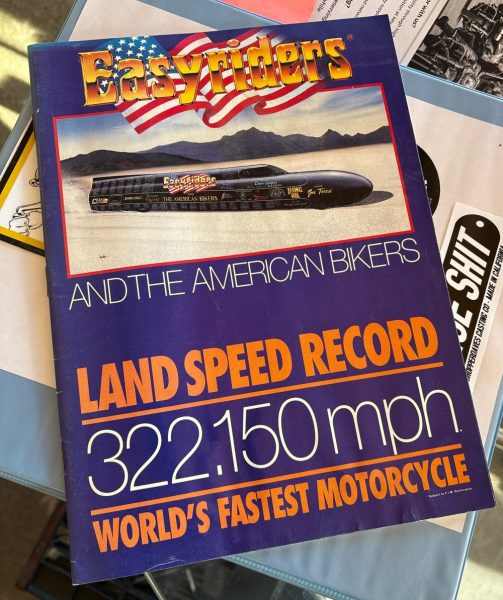

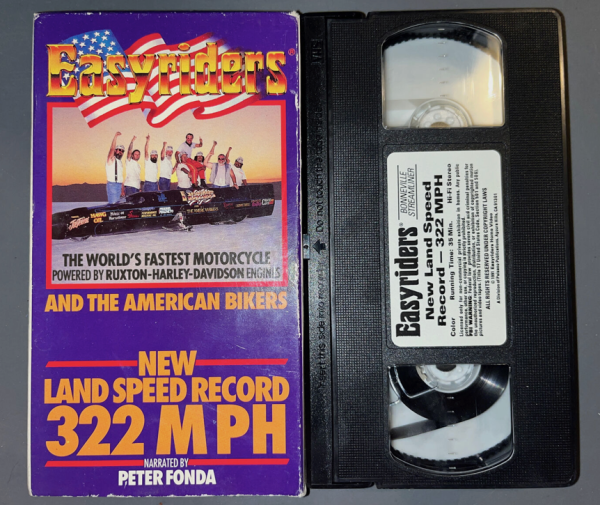

The Story behind the World Fastest Motorcycle for 16 Years at 322 mph from 1990 to 2006

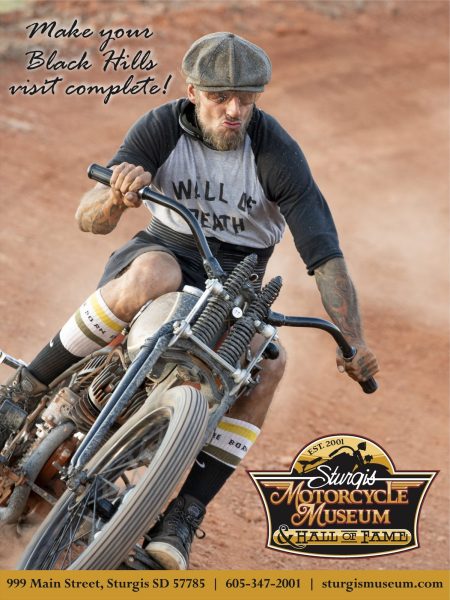

The Sturgis Motorcycle Museum Board recently received an amazing opportunity to exhibit the Easyriders Streamliner during the 85th Annual Sturgis Rally.

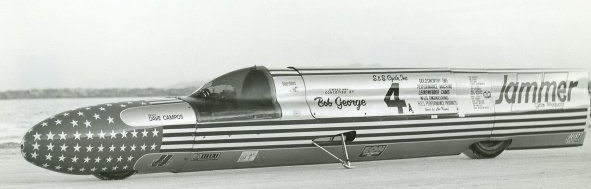

The saga started in and around 1971. I recently escaped the Vietnam era, but not before meeting Andy Hansen on the USS Maddox DD731. A reservist on his monthly training excursion in Long Beach, California, we hung out and talked motorcycles. Building his first custom motorcycle in Culver City, his mentor lived close by. Round and friendly Bob George, a master Harley engine builder would become one of the first guys to build a streamlined motorcycle. An incredible story!

One of Bob’s constant obstacles became financing, so I set up a meeting with Joe Teresi, an owner of Jammer Cycle and an Easyriders Magazine Partner. Joe graciously took on the project and, for a decade under the management of Mil Blair, his partner, the Jammer streamliner was born.

BONNEVILLE BASICS

Over seven decades passed since the first maniacs rolled vehicles onto 224 square miles of compressed salt on the Great Salt Lake Desert, leading into the Great Salt Lake.

The tough, asphalt-like surface appeared to be dense and thick, still it varied from 3 inches to a foot thick before the water table emerged. Just a slight blast of rainfall raised the table to form a lake over the crystalline salt. During extreme heat conditions, the surface cracked and created pits and grooves. During winds and rains, the shell changed to slippery mud and erratic surfaces. The ideal condition was moist and smooth, and it’s still extremely unpredictable.

As many as three tracks can be operational at any one time. During the Bonneville Motorcycle Speed Trials, the crew refined a 1-mile course for ‘Run What Ya Brung’ Competitors. Check the rule book. There are still multiple requirements for this class. They planned another 5-mile track for most hot rod motorcycles, and finally, an 11-mile long Streamliner path.

An amazing place, like the surface of the moon, spectators annually witnessed the largest outdoor photo studio on the planet, with a pure white deck and unobstructed blue sky.

A FIRST IN SO MANY RESPECTS

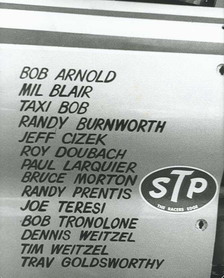

In 1987, I returned to Easyriders Magazine and, shortly afterward, Jammer shut down and Joe Teresi took control of the Magazines and Streamliner. It became the Easyriders Streamliner, supported by 10,000 Easyriders Magazine readers, from all over the country. For the first time, Bikers stepped up to support an American made attempt to take on the ‘Record Of Records,’ the Motorcycle World Land Speed Record (LSR). Each $25.00 participant received an Easyriders Streamliner t-shirt sporting a David Mann painting of the liner and their name pinstriped on the side of the liner.

After significant changes and mods by Keith Ruxton and crew, including myself, we rolled to Bonneville in 1989, and were support by the largest crowd in the history of LSR attempts. Riders endured long runs from as far away as New York, Florida and California, put up with harsh elements and poor camping conditions. Die-hard riders prevailed the non-stop, encroaching salt and wicked winds to watch the Easyriders Streamliner make history.

We needed a place to wrench, and Micah McCloskey and I rode to the abandoned Wendover airport on the outskirts of town. Fortunately, we befriended a guard who allowed us to use the hanger the Anola Gay used at the end of WWII. After three days of non-stop wrenching, tuning and safety checks, we started to make shakedown passes on the salt and increased the nitrous load from 60 to 80 percent. Initial passes reached 264 mph and touched on 300 mph. We were forced to break an average speed of 318 mph, the previous Kawasaki record held by Don Vesco.

In September of 1970, he set the Motorcycle Land Speed Record of 251.66 mph at the Bonneville Salt Flats in a streamliner powered by twin Yamaha engines. Less than a month later, Harley-Davidson factory broke the record with Vesco’s longtime friend, Cal Rayborn, at the controls.

“Since Cal (Rayborn) and I were good friends, I knew Harley was going to set the record,” remembers Vesco. “I made sure I got my contingency money from Yamaha and all my other sponsors quick.”

In 1975, Vesco broke the 300-mph barrier in the Silver Bird Yamaha (powered by twin Yamaha TZ750 motors). Then, in 1978, he broke his own record, turning 318.598 mph in a twin Kawasaki turbo rig. That record held for 12 years. (AMA Motorcycle Hall of Fame)

Tuesday, September 26th, 1989: Time ran short for the Easyriders team and bad weather closed in on the Bonneville Salt Flats. With the nitrous load pumped to 88 percent, the Ruxton-built 90-inch Shovelheads sang to 6700 rpm (calculated to reach 320 mph). But, as Dave Campos, the pilot, entered the timed mile, the soft, aged front tire disintegrated slowing him to 280 mph. Just 2.5 miles later the tire bonded molten rubber to the salt and the steel rim dug into the erratic surface, spinning the liner into a rolling, tumbling, flying crash. Dave walked away…

Our final pass netted an average speed of 284 mph which set a record for the fastest Harley-Davidson perhaps forever. The effort was done, but we returned the following year…

“We were down—but not out!” Said Joe Teresi. The American Spirit was well represented by the crew and the thousands of sponsors who backed the effort. With another 10 percent bump on the nitro, nitrous boost, and a taller gear, we could smell victory. Just as General MacArthur said at Bataan during WWII, “We shall return!”

Breaking the Motorcycle World Land Speed Record ain’t easy. Reminded repeatedly during the 16 days spent at Bonneville in 1990, we wore out tires, chutes, engines, transmission gears and brakes. We ran out of sparkplugs, chains, oil, fuel and even blew a piston out of the tow car! About the only thing that didn’t give up was the team spirit of the crew. The ER Team’s spirit never gave up!

We started making passes on June 29th, but ran into issues with the solid billet front wheel. On July 1st, the liner was off and running again. Changes seemed to be working. Dave encountered vibration. “I thought I could drive through it,” Dave said. At 280-300 mph the front wheel slammed back and forth, lock to lock in a high-speed wobble. The liner flipped, rolled, and it slammed to the salt. Dave walked away with only a bruised knuckle.

Anyone in their right mind would have packed up and gone home, but not us bikers. We needed rubber tires mounted and balanced, engines checked for damages, frame checked and aligned. A new canopy needed to be rebuilt, and every panel of the body needed work.

By the 4th of July, with the help of individual sponsors and a Salt Lake City Plexiglas manufacturer, the liner was back together.

July 5th: They headed into their first pass with a rubber front tire, but a chute deployed. By early afternoon, the repaired liner made a 305 mph pass, backed-up with a 301 for another national record of 303, but an oil leak caused an engine fire and burnt injector lines. Back to the hanger for repairs…

July 6th: The team faced the starting line at first light, but a 10 mph crosswind prevented passes. By 8:30 they made a 317 mph pass. But, during the following pass one cylinder started oiling during the run, slowing the liner to 299. They decided to return to the hanger and install new engines.

Saturday, July 7th: After an all-nighter, with the crew working shifts to install new engines, it was mid-afternoon before the team was ready. After tuning passes and more tuning, Dave cranked off a 291 mph pass with a missed shift. Then, a 293 mph run with another missed shift, and they ran out of daylight.

Sunday and Monday, July 8th and 9th: The specially built Muncie gear box took a beating during the crash and needed attention. After nine days on the salt with four hours sleep every night, the crew needed to adjust to 16-hour days and 8 hours of sleep. They shifted schedules, adjusted the transmission and checking the liner over, thoroughly.

Tuesday, July 10th: Handling and shifting problems emerged and it was decided to rebuild the trans.

Wednesday, July 11th: More issues with the front wheel and tire. The tires were last manufactured by Firestone in 1967, rated at over 400 mph, but very porous with age.

Thursday, July 12: At it again at first light. At 8:22 Dave made his first pass, shifting perfectly, but running lean at the top-end. Easy fix, but the wind kicked up. They had but two hours to up the 316 pass with a record breaking 326 mph run.

Everything looked perfect, they were given the go-ahead. All dialed in and the liner running strong, the timing light malfunctioned and canceling the run. Handling problems ensued, adjustments made, but then the tow car engine blew. Some 17 full throttle tows did their number on the hotrod Pontiac.

The only tow-vehicle available was a 454-powered Chevy rodeo truck. It could tow the liner to 60-70 mph, but not 100. At 8:58 they turned a solid 322 mph pass, giving the liner another national record of 319 mph with a thinning front tire and out of fuel. Plus, the high-speed chute’s life ended, worn out from dragging on the salt. Frantic calls went out to Deist for a chute to be air-freighted to us. Al Teague, at Speed-O-Motive, in Salt Lake City, found two used front tires.

Friday The 13th: By noon the tires and chute arrived, and they owned the last 20 gallons of fuel in Salt Lake City, enough for four runs. The chute was different yet workable, but the tires were in worse shape than the ones we had.

The rear tire needed more clearance, and the tow truck starter solenoid quit. Was it Friday The 13th???

Saturday, July 14th: Sponsors help create a longer track for the Chevy tow vehicle. The early morning run left the crew with a disappointing 301 mph run. Oil in the rear injector told the story. They lost a piston.

By early afternoon, they were ready to run again. During the towing process the truck slowed, the pilot clutched, broke the rear tire loose and Dave drifted to the left side of the course directly into a piece of PVC pipe marking the 1/2 mile. It dented the nose and shattered the Plexiglas canopy. Fragments cut Dave and the canopy was toast.

While most of the team kicked back, Leon and Al Bulling, and an unknown sponsor, repaired the nose and the canopy in the heat of the afternoon. Amazing! By 6:37, the liner stormed up the salt and bingo! 321.4 mph!

Within the two-hour requirement, they needed at least a 322.139 pass. After caster adjustments, Dean and Kit packed the chutes and checked the chain. Bobby and Jerry changed the fluids and fuel levels, including the nitrogen pressure in the tires. Keith Ruxton and Micah read plugs and mixed the fuels.

Halfway into the run, Dave slid to a stop, “It won’t steer left!” Burnin’ daylight, they towed the liner back to the start line. They needed to make one more pass quickly. That wasn’t the last hiccup. Another stop and a wet start forced engine corrections. With little time left, another pass started with towing issues, Dave hitting salt bumps, going airborne and the front tire shredding. Dave nailed it a final time and flew through the timing lights at 322.870, for an average of 322.150, and the ‘Record Of Records.’ Amazingly, the Easyriders team brought the World’s Fastest Motorcycle Record back to America. And now the Easyriders Streamliner will be proudly displayed in the Sturgis Motorcycle Museum for the 85th Annual Sturgis Motorcycle Rally.

Team:

Joe Teresi—Owner

Dave Campos–Pilot

Keith Ruxton–Crew Chief

Micah McCloskey—Assistant Crew Chief

Leon Hatcher—Field Director Easyriders Rodeos

Bobby Torres—Mechanic

Jess Pendegraft—Crew Mentor

Keith Ball—Man-About-Town

Kit Maira—Communications and Wiring

Jerry Pinedo—Tool Man and Parts Chaser

Dean Shawler—Announcer Parachute Rigger

Chris Svanberg—Custom Machinist

Rick Schaal—Parts Truck Driver

Dave Beard—Helper

Carl Beard—Safety Check-off

Legendary!

Thanks Rick,

An epic journey…

–Bandit