Road King 11/08/05

By Robin Technologies |

Around mid June Kerry and myself were organizing our trip to Sturgis, when Bandit contacted me an asked how would I liketo ride the Road King to Sturgis. Immediate thoughts were Wholly Shit, I’ve read all about the King on Bikernet and watchedthe different stages Bandit has put it thru, so I was very familiar with it, and for Bandit to be asking me was really a big deal, meaning, I felt honored enough when Bandit invited Kerry and myself to join them on the ride, let alone ride his bike. So youprobably guessed the answer was a big >>>>>> Yes Sir !! thank you very much.

For the readers who aren’t familiar with the Road King, I’ll enlighten you. It started life as a stock 2003, 100th Anniversary model.Bandit said he designed the bike be a big bad assed, blacked out touring bike with heaps of attitude. Bandit and his crew wanted to use as many H-D parts as they could to prove you could build a mean assed bike out of Harley Davidson’s catalogue. They started by blacking out the dash, a set of one inch lowered air shocks and a detachable back rest along with some neat touring components. With the help from a dealer for some more involved tech mods to gain horsepower and some low-down torque, they came up with a formula by adding performance cams, Screaming Eagle Heads, air cleaner kit and two into one pipes powder coated black, giving them 68 horses compared to 60 and torque was 76 pounds with a 6 pound increase. Next they installed a factory oil cooler which Bandit tested on a run to Barstow saying how it kept the oil at a very reasonable temperature which is critical for long term, Twin Cam reliability.

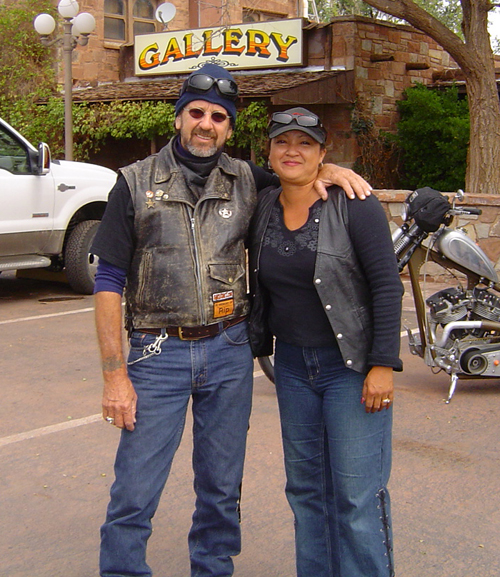

Fast forward to Sturgis, August 2005 and Kerry, my wonderful bride, and myself arriving at the Bikernet Headquarters being greeted by Bandit and the lovely Nyla. We were enjoying a beer while having a grand tour of their unbelievable home when Bandit said, “Get ya helmet Goddamit, we’re going for a ride.”

It’s hard to explain the excitement that was welling up inside of me, especially when I first laid eyes on Bandit’s bare boned, mean as shit Shovel, I swear it had a look like, let’s go, I’m ready. And right beside it sat the Road King.

It definitely looked like itwas ready to do some very serious miles, man. It looked beautiful, all blacked out like a road warrior ready for action, 16-inch apes reaching for the sky, a very comfortable looking seat and a detachable back rest for Kerry. I gotta tell you these two bikes were like chalk and cheese, the Road King had all the creature comforts and Bandit’s Sturgis Shovel had absolutely nothing, excepta little back fender and a sprung seat, Shit !!! and he’s riding it to Sturgis, tough sonofabitch, I thought to myself.

Just as the sun was setting over Long Beach we fired those puppies up and peeled out of the Bikernet Headquarters like two crazed maniacs going for their first ride after a long cold winter, ( sound familiar Bandit ). Seriously thou, we cruised around Long Beach taking in the sights and both of us getting used to our rides. We both had grins from ear to ear, especially when we twisted the wick on these babies, I was blown away, the King with it’s sheer size and weight, had some serious acceleration, man. I was impressed plus having a lot of fun and Bandit’s shovel went like a rocket, with it’s power-to-weight making it an awesome ride.

This was going to be my 4th trip to Sturgis (beginning in Australia) and I knew 100 percent this trip was going to be very special, I was feeling right at home on the Road King, everything was perfect except for the bloody windscreen, I think it was set up for Bandits 6′ 4” frame and I could not get used to it, but Harley had it covered. Two seconds and it was off, no problem.

I would love to tell you about our trip to Sturgis, but it’s been covered by Bandit and Johnny Humble, the young gun from Texas, both really great stories and you can still check them out by going to The Events Coverage in Bikernets Department Site.

It’s hard to put into words, the true feeling of this road trip with such great company, I will say that we were very privileged to get to ride with them, even thou we live on the other side of the world, I know that Kerry and myself have forged life-time friendships and hopefully will get to do it again some day.

I have been privileged to ride a lot of bikes in my time and I must say the Road King was bloody brillante, we covered 4000 miles all up, came across all types of weather (as we all do) including high altitudes where the King never missed a beat with it’s superb fuel injection and very smooth motor. Seating was great, and I just loved the apes. Not only do they look really cool with an attitude, they were really comfortable.

I will post some photos of our trip that you haven’t seen and would like to do a follow up of our trip from where Kerry and myself parted company from the rest of the crew, returning to L.A. via Denver, Santa Fe, Sedona and Vegas.

I would like finish up by thanking Bandit and Nyla for their friendship, hospitality and giving us such a great time, not forgetting the use of their Road King.

Okay guys thats a wrap, hope you like it.

Road King 12/04/02

By Robin Technologies |

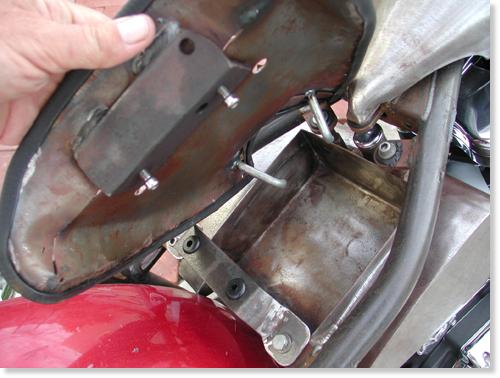

Yep, these techs will be backwards. I just rolled in fromArizona after the first 1,000-mile test ride after installinghighbars, performance parts, and modifying the windshield to fit thehighbars. So why publish the techs backwards starting with thewindshield? We’re lazy. This one will be short and the next two,since Frank Kaisler was involved, will be mammoth techs withthousands of photographs. Hang on for them, but if you’ve installedhighbars on a Softail or a King model and have long arms like myself, the windshield may be a problem to attach, but there’s acareful, simple cure.

First put the shield in place and decide if you can endure ahandlebar adjustment or not. If you pull the bars back in line withthe front end, the windshield will fit without a problem. You mightcheck it for 80 mph flexing which could cause rubbing against thebars, cables, brake hoses or wiring (if you didn’t run the wiresinternally). I took short wire ties and held small soft stripes ofrags around the cables that would have been damaged.

So I shoved the bars forward until the windshield would havefallen off the front-end. I’m not a big fan of windshields, but whenyou plan a ride through a 1,000 miles of rain, cold and wet highways, it’s a plus. I used the adjustable windshield from Harley-Davidson which allowed me to raise or lower it. I discovered that the lowered position is actually more comfortable in the rain. If I had raised it, I would have looked through the shield which was scattered with water and streaks. Visibility sucks and distraction wasoverwhelming, so I lowered it and my visibility was perfect while stillmaintaining the comfort and protection of the shield.

So what the hell did I do? I cut scallops in the plasticshield. First I marked off the area of the shield that had to beremoved with 1/4-inch masking tape and began to grind through theplastic with a bench grinder, the finer of the two stones. I tookcare to keep the edge of the plastic aimed down so the stone wouldn’t grab the sonuvabitch and crack it. I ground one corner then the next to search for a basic rounded feel. I avoided sharp edges or grooves that could crack. Since this was no perfect established science, I took my time slicing notches then slipping the windshield into place. I went back and forth to the grinder over and over. You might want to wear a breathing filter during this process and eye protection.

Once I was close to the finished area on one side, I took thewindshield to the vice and with leather pads on either side of themounting bracket clamped it down. Then with a high speed drill and a burr bit began to cut and shape some more. This, I found was difficult and took care not to allow the bit to grab and cut into theclear surface, but I was able to clean the edge some more. Ire-installed the shield again and determined that I was damn close.

Keep in mind that this was a last minute operation onThanksgiving day, between writing projects and packing for a run tothe desert. As the evening closed in it began to rain, a rarity inthis neck of the woods. I jogged in the house and flipped on theweather channel. The gods of the Roulette table had decided that Iwas not supposed to ride this weekend. The only rain east of theMississippi was dead over the 10 interstate from Los Angeles to theArizona State line. That made the windshield project even moreparamount. I dashed back to the garage.

Once I was close to the necessary fitment, style andprecision matching became a consideration. I ran a piece of maskingtape up the side of the stainless steel strut straight up the shieldas a measuring guide. Then I measured up from the horizontal strut to where the cut began. With these measurements I was able to compare them on the opposite side for an even scallop into the shield. I went back to the grinder and to the burr device for the final shaping. I continued back and forth a dozen times from the grinder then the high speed drill and back again. Once I had it nailed down, predominately with the grinder, I used an emery bit to smooth the edge of the Plexiglas.

That completed the cutting and shaping although the unitdidn’t lock entirely into place. I knew that once on the road thewind would prevent it from escaping. One small wire tie held thespring lock on the detachable windshield to the clutch cable foradded insurance. Just under 1,000 miles later I pulled back into SanPedro with a completely successful ride under my sore ass, provingthat careful mods to the Plexiglas windshield are completelypossible. Rah, rah.

Saddleman Improves the Amazing Shrunken FXR

By Robin Technologies |

SADDLEMEN MODS TO THE SHRUNKEN FXR–In a world where over promising and under delivering has become all too common here is a gem I must share. The Bikernet built Shrunken FXR has become my daily rider and needed a couple small adjustments to be just perfect for me.

One detail was the too small seat or the bike was too fast (pick one). So I rode my bike over to meet the nice folks at Saddlemen and see what they could do to help me out with my seat. Upon arriving at the Saddlemen facility I spent time with guys from the front office to the guys in the shop ( all of whom took great interest in my motorcycle and the seat they were going to design and build). I noticed from the get-go these people were all riders. I shouldn’t be impressed by that, but there are so many folks in this industry who don’t even ride anymore.

We discussed what I needed (lumbar support) and a lip on the edge of the seat to keep me from being bucked off or sliding onto the rear fender. We also discussed the lines of the bike and that in the case of the Shrunken FXR , less was more. After the team and I spent a great deal of time figuring out what we wanted and didn’t want I was able to walk around the shop and see the whole seat making process from start to finish. man was I impressed!

So many talented folks all working together to put out an amazing array of products designed by and for riders! It was a real treat to see this and made me truly appreciate what they do much more. Great companies, in my opinion, are made of the people who work for them. So I left my bike for mock-up, and received a call back in a week.

When I showed up I saw the foam of the seat had been formed and pan had been constructed. We discussed coverings and stitching, again less is more. They got it and even pointed out to me the lines of the bike would be reflected in the seat.

Three days later I returned to pick up my bike and see my new seat! A seat is the finishing functioning touch to any motorcycle (much more than something you sit on) it must reflect the bike while being comfortable and a key suspension element.

I was so happy to see the seat. It looked amazing and really I could not have imagined it any better than they had built it. I put my helmet on, thanked them and jumped on the bike to ride away. First thing I noticed was the lumbar support made the bike so much more comfortable to ride and kept me in the perfect position to reach all my controls.

The biggest difference was when I hit a huge pot hole (tons of em’ in area) was my ass stayed firmly planted in the seat and the impact was minimal. The seat made my bike complete.

Can’t say enough about how impressed I was with the Saddlemen crew and facility, in short they made my custom bike have a perfectly functional and stylish seat. The perfect blend of function and form. I suggest anyone who needs a seat built or customized give them a call. They are a family team of bikers designing and building products for bikers. I like it!

–Buster

Mudflap Girl Part 4, the Spitfire Frames to Rollers

By Robin Technologies |

Suddenly we’re smoking on the Mudflap Girl FXRs, but the week after I received the frames, I had to jump a plane to New Orleans and ride a Victory to the Smoke Out. I was itching to work on these bikes.

I survived the Smoke Out, and since I just spent 1000 miles in a Victory saddle, I was motivated to get back in the wind. We looked down the barrel of the ticking calendar as I returned from the East Coast on Sunday and Monday the 27th of June I stepped back into the Bikernet shop and faced two Mudflap Girl FXRs on lifts ready to rock. I dove in making lists and started to assemble my frame and the Spitfire girder front end.

Building a bike is like falling in love. We all have our dream of the perfect woman, and each time I build a bike, that notion is the driving force. I’m building the perfect romance, with all the best intentions. I want this one to last forever, take me anywhere I want to go, and be my Mudflap girl baby in spirit, appearance, and function.

I would imagine the same mental scenario applies to a home building architect. In fact, we have focused some of our efforts on creating a vintage motorcycle coffee shop in the front of our building, Bandit’s Barista. Talk about a daunting process involving several city agencies. Let’s leave that one alone. Sin Wu came to a meeting this morning and immediately quizzyness engulfed her and she was forced to leave. “It’s too daunting,” she said.

We are so fortunate to be able to rely on our friends and compadres in this industry and build whatever motorcycle we want, then go for a ride without severe governmental restrictions. Meanwhile, back in the shop, I was completely astonished at Paul Cavallo’s talents and shop capabilities. He designed and manufactured every element of this classic girder front-end. As I installed his internal fork stops and began to assemble the front end with the Foose-designed MetalSport 2D wheel, I was constantly blown away at every intricately machined piece.

Although Dr. Willy bitched about the top motormount on the frame, I didn’t have a problem with it. It just forced us to face another brief obstacle, which will ultimately create a very cool linkage issue with a 7/16 pivoting rod end on the top like most FXRs.

But I’m getting ahead of myself. I installed the fork stops, then the Biker’s Choice neck races, the Timken neck bearings, and the Metal sport front wheel on the Spitfire ¾-inch axle. Paul set up his frames to take stock Harley 2000-2007 front and rear brakes. We are going to use factory brakes on my son’s FXR, but I’m running with GMA brakes currently manufactured by BDL.

I had to come up with a mounting system using Paul’s stock H-D brackets. It was a trick but worked out, with brass rod and steel spacers. I messed with it for a couple of hours. Ultimately the GMA caliper was centered over the MetalSport rotor and in a terrific position for bleeding.

Then I started to install the girder rockers and bronze bushings. I was careful to grease every component, and again I was impressed by the precision fit with each bushing and axle. I installed the trees on the fork stem and rolled closer to installing the girder structure. Everything just slipped together.

Unfortunately, I was missing one element of the front end, the brackets holding the shocks in place, so I shifted to something fun, installing mudflap girls on the Spitfire side panels. They make these Zeus fitting fastened aluminum panels out of street signs. The mudflap girls came from 2Wheelers in Denver, but the Arlin Fatland and Donna team is currently headed for Sturgis to the rally, which reminded me that Sturgis is just around the corner. If I had another month, we’d be riding the Mudflap Girls to the Badlands.

Next, I needed to install the rear MetalSport wheel and driveline. FXRs are tricky in this regard. The entire driveline from the engine to the rear wheel needs to be installed at the same time. We started with the swingarm, using the Custom Cycle Engineering swingarm axle and retrofit kits. Here’s what CCE says about these conversion kits.

SWING ARM RETROFIT KITS

Custom Cycle Engineering has developed a swing arm conversion kit that replaces the stock Cleve Bloc style swing arm bushings with spherical bearings. The conversion covers all the FLT and FXR models from 1980 to 2001. The swing arm conversion kit coincides with Harley-Davidson’s change from the Cleve Bloc bushing to a spherical bearing in all the 2002 and up FLT models.

The conversion over to spherical bearings in the early models dramatically changes the handling and tracking of all the FLTs and FXRs. The sticksion at the swing arm pivot is greatly reduced with the new spherical bearings. This allows for the swing arm to react quicker to any harsh road conditions, keeping the wheel in contact with the road. The use of spherical bearings also helps negate any lateral and torsional movement in the swing arm by the shear dynamics of a spherical bearing.

The swing arm bearing conversion kit is one if the positive answers to the inherent ill handling problems of the popular dresser models.

It was easy to install the new spherical bearings using our shop press and the special tool CCE provides with their kits. We pressed them into place with the CCE guide tool and red Loctite. Then we installed the swingarm on the transmission and the whole tamale in the frame, since the oil tank was out for sealing and some flat black protection. Ray C. Wheeler gave me a hand. We slipped the JIMS transmission and swingarm through the back of the frame sideways, then turned it level and aligned it with the frame mounting system. My son scored some used bare aluminum cleave blocks, and I ordered new H-D rubbers from Biker’s Choice. Watch how the rubbers and cleave blocks are mounted. They are like a small four-piece puzzle with guide pins in particular locations.

With the JIMS 6-speed transmission in place, we jacked up the trans for engine installation. With a centered Biker’s Choice front motormount bracket in place and the rubber biscuit we were ready to rock. Willie helped guide us through the process. Willie is a master with FXRs. He’s worked on bikes, and rebuilt engines and transmissions forever. He knows all the tricks.

With the driveline in place, I started to monkey with the D&D pipe mounting, mounting brackets, and mounting the GMA rear brakes. The brakes became tricky, since Paul designed a tougher and wider swingarm, but it worked out perfectly. I’ll get to that puppy in a minute. I noticed that the trans didn’t come with the final seal and locking nut, plus we needed to reach out to JIMS for a proper offset sprocket for the 180 Avon tire. Since this is an 80-inch Evo, I wanted some gearing advice for the 6-speed overdrive transmission.

Here’s what James Simonelli wrote while packing for the Sturgis Rally and preparing for their install facility. Call them quick, if you want an upgrade while you’re in town.

MUDFLAP GIRL GEARING ADVICE FROM BAKER DRIVE TRAINS–

22-51 with normal 37-24 primary is 3.57, pretty lively! In 6th (.86)

you would have 3.07

23-51 37-24 gives 3.42 and 2.94 in 6th. I think that’s where I’d start.

To compare, most stock late models with 70/32 belt and 36/25 primary are

3.15 overall in 5th.

It’s nice to be slightly below 3.0 in 6th for 75 mph cruising. If it’s a

stoplight burner, go the other way.

Baker will be set up in Sturgis on Lazelle performing installs. If you would like your 5-speed modified into a 6-speed, or a special Baker oil pan added to your dresser, set up an appointment soon, and tell ’em Bikernet sent ya.

We ordered a rear sprocket spacer and a dished 51-tooth sprocket from Biker’s Choice. It’s always somewhat a roll of the dice and I try to build a selection of spacers to allow me a variety of spacing options. With the JIMS ½-inch offset 23-tooth sprocket and the centered wheel, the transmission lined up perfectly with my brand new O-ring chain. It had never been removed from the crumbled box after a trip or two to Bonneville. I pulled it free from its container and the bastard was covered in rust.

Chad from JIMS sent me a photo of the mainshaft seal-installing tool. I also ordered the seal spacer, but had an installation question.

“Tech says bevel side faces into trans,” said Chad. “I have attached an image of the

needed tool, #786.” I dug through my special tool bins and found something from JIMS that would handle the trick.

In the meantime, our sheet metal returned from Jim Murrillo, who sealed the tanks with Caswell and gave the exterior a protective primer coat. It was a rush to slip the two gas tanks into place but we ran into a problem with my oil tank. I almost had to take the engine and the trans out of the bike to return it to its rubber mounts. Ah, but we succeeded.

Now all the major elements are in place, but the Sturgis Run is moments away. We plan to load my Sturgis Shovelhead onto our trailer, with the 120-inch Panhead, the Salt Shaker for Mr. Wheeler to ride. We will snap the trailer to the Bikernet hearse and cut a dusty trail in a couple of days. While I’m in the Badlands I’ll be thinking of Mudflap Girls and getting back to the builds. I’m sure I’ll return with more ideas, and next year will be the year of riding FXRs to the Badlands.

Hang on for the next installment as we mount up the Trock-modified CV carb on my ride, and the Mikuni 42 mm on my son’s bike. We have wiring harnesses from Wire Plus, and I have a rare intake manifold from H.E.S. and Branch, that was ported by John O’Keefe. We’ll be rolling close to final assembly as I install my BDL belt drive system and Frank’s mid controls. Goddamnit, I can’t wait.

Sources:

Spitfire

Biker’s Choice

JIMS Machine

MetalSport

BDL/GMA

Wire Plus

Branch O’Keefe

Bennett’s Performance

Custom Cycle Engineering

The Amazing Shrunken FXR Project

By Robin Technologies |

This here cardboard box full of odds and ends was where it allbegan. Or was it just an idea? Or maybe too much Jack Daniels. Ormaybe Bandit was tired of me whining about it. Anyway, like a beggar on the streets ofCalcutta, or Blanche Dubois in “A Street Car Named Desire,” I depend onthe kindness of strangers. And there ain’t none stranger than Bandit’scohorts. Strange but mighty generous, such as Rogue, who cut us adeal on the FXR frame and forks. We’re relying on Joker Machine forall the quality components including the end caps for the swingarmto get this puppy on two wheels.

We couldn’t figure out what this chopper was going to be. Maybe thedefinitive Rat Bike, or a stretched-out steel spider with a hellishV-Twin, or whatever kind of Rube Goldberg, slapped-togethermonstrosity we stumbled upon.

The critical thing is that I’ve got short arms and legs (kind oftroll-like) so whatever we made, it had to have a low center ofgravity. I tried riding Bandit’s Buell, but when I came to a stop, myfeet didn’t touch the ground. So we agreed that the frame had to damn nearscrape gravel. I kind of fancy myself an iconoclast, so I didn’t want tobecome another ad for yuppie motorcycling. Bandit wouldn’t let mepour acid on the thing to give it a lived-in look. If it was going to be a Rat Bike, heproclaimed with bombast, it had to be cool. Well, cool and twobucks might get ya’ a bottle of warm beer. I was determined to make my mark,rat-assed or not.

Bandit suggested that we chop a couple inches out of the frame.

OK, I sez. Bobbed fenders? Bob’s yer uncle, I sez. Narrow the fender railspace? Narrow it is, sez me. Now we’re rockin’. But to tell ya thetruth, it’s still a frame sittin’ in mid-air and a box full of used parts.

But don’t count us out yet. We’ve got a sizzling summer approaching,I’m outta work (I ain’t teachin’ summer school), the Jack Daniels is flowin’,and we’re fillin’ up more cardboard boxes. Bandit’s a tolerant guy, he’s gotthe summer (if he don’t go sailin’ off to the seven seas), and me? I got abrain bubblin’ like a pot o’ hot chili. No tellin’ where thiscrazy-assed bikeis gonna’ take us.

We threw the potentially radical chopper that Bandit and I have banged together up to this point, into the back of my pickup and jammed over to see the Doctor. Dr. John, the frame doctor took one look at the bike in the back of my truck and shook his head. Behind that scraggly beard and those beady blue eyes there is a wealth of experience. He’s seen a lot of biker hopes and dreams, sometimes nightmares, come through his Anaheim Hills shop. He’s managed to salvage most of them. His wry humor snuck through that tangle of beard, “Hmmm, that’s one nice looking Rev-Tech engine.” Bandit ground his jaw, I fidgeted, kicking at the asphalt.

He looked at our hopeful faces and didn’t want to disappoint, “Ok, I’ll take the challenge, but it’s going to take me a couple of days to figure out how the hell I’m going to hammer this thing into shape.” Bandit and I smiled, knowing that the Dr. was going to save our scrap-iron baby.

The whole idea was to shrink the Pro-Street frame around the engine, with just a slight additional rake to the front end. I’m 5’8″ but with short arms and legs, so we wanted the bike frame to be custom fit to my body- frame proportions. We had been looking at some of the bike designs from Japan (where the guys are built more like me) for inspiration.

Just with the modifications that Bandit and I have done so far gives some hint as to the unique feel of this design. With the massive Rev-Tech 88-inch engine and 6-speed Revtech transmission squeezed into place, it looks like a Star Wars space sled. I kind of like the rusty, unpainted Pro-Street frame. It gives it an elegant rat-bike look. But then that’s just my twisted sense of humor.

With the rubber-mount engine we have to leave some room for wiggle, so the frame can’t fit like Saran-Wrap. Cutting an inch or so off the swing arm will bring the back tire teasingly close to the inside-front of the swing arm. With a tiny back fender and stretched our front, the ass-end of the bike will look like it’s tucked in below the seat. I said it’s going to look like a running, weird-assed wild hyena. Bandit didn’t care for the comparison and shook his head discustedly.

When we built the Blue Flame, the whole bike was engineered to fit Bandit’s stretched-out body dimensions. Not every bike rider is built like that gangly orangutan, Bandit. So we’ve put a lot of thought into the design of this bike, in terms of scale and proportion. Even the choice and location of foot pegs, shifter, brake pedal, style of handle-bars, and primary shield, will reflect these concerns.

While the doctor is bending and welding the frame into shape, we will be working on paint design, tank and fender design, and ways to clean up some of the wiring, break lines and cables. Or maybe we’ll just fuck off until the doctor calls. Hey, it’s summer and we need to mellow out some.

The day started moderately okay. Bandit and I were going to zoom up toIrwindale to talk to Geoff Arnold at his Joker Machine headquarters to order a raft of parts for the Shrunken FXR, then toAnaheim Hills to meet John the Frame Doctor to check out the progress on myframe, we thought we might also catch lunch with Scooter, our notorious Bikernet criminal attorney, then a leisurelyglide back to San Pedro. No sweat, you say?

The closer we got to the foothills, the morning mist mixed with thecarbon monoxide of a million or so cars careening all over the L. A. basin.Ocean breezes pushed this toxic stew into the eastern edge of the foothills.By the time we got to Irwindale, the Bandit and I were like a couple ofbreakfast eggs sizzling in a skillet.

Bandit called the Doctor to confirm our plan to pop by. No way, no how,says the Doctor. He’s having a PMS kind of day. He hasn’t started on mybike. He’s got a hemorrhoid of a project to hammer out before he can starton mine. Dr. John also repairs sportbike frames and reported that sometimes the frames are so mangled that, well they should be shredded, not repaired. He was up against one of those. So no doctor visit.

A call to Scooter gets about the same results. He’s got to work so nolunch. The day was starting to feel cursed and doomed.

So we knock on the door of Joker Machine. On the other side of the doorwe could hear the banshee howling of an animal possessed. As we walked in,Studley the Joker mascot, attacked with teeth bared, an upper lip curled inschizoid disdain. The rabid Chihuahua snarled, yapped, barked and yelped ina psychotic frenzy. Damn near took Bandit’s arm off when he bent down to patthe little demon on the head.

Geoff grappled with the chain, holding back the crazed critter andwelcomed us with a hearty handshake. Geoff was a gracious host, showing usall the latest Joker products and a few of the Joker toys including their new truck.

Joker’s new Renegade traveling drag racing garage and party room.

Brian was outside welding together what appeared to be girders for abridge. It turned out to be the sturdy ramp superstructure for the improvedJoker Machine stationary Dyno. Like everything at Joker Machine, expertise andquality construction dominated. That’s one reason we chose to use Joker controls, footpegs and aircleaners and their new rocker covers. The blue flame was domintated with Joker components primarily due to fit and finish. Bandit has never purchased a Joker part and had to modify it to fit.

Secret Joker Dyno testing facility. What will they think of next?

Joker is in the process of developing a testing facility for a new line of products, yet to be released to the public.

Over lunch and beers we discussed our design ideas for the new bikesBandit and I are working on. The crew of Joker Machine looked at each othercautiously as Bandit babbled vague musings about “design integrity” and”hidden exhaust systems” or “creating a dense engine compartment.” I chimedin, gesturing with my hands, waving my arms to demonstrate the contours ofthe frame and tank.

Geoff grinned and said that he thought Joker Machine was up to the task.Bandit laughed and said that we had planned to integrate a number of JokerMachine products into our new bikes. Joker Machine, Bandit said, is the bikeparts distributor of choice. For example, he said, products like theadjustable foot pegs allow for adaptation to the individual rider needs.

In addition to the adjustable foot pegs, we intend to integrate into ourdesign with Joker Machine tear drop vents, hand controls and a Joker air cleaner. Weplan to modify Joker Machine forward foot controls to mid-controls.

The Joker Machine crew grudgingly finished their beers and got up toreturn to work. We all walked out side to a blast of heat that would curlthe devils eyelashes. Brian climbed into the back of a Joker truck housing a new V-Rod for product development. Brian recently graduated from advanced schooling in metal fabrication and the Joker crew is looking to him for inspiration and guidance into new product arenas while their CNC design wizard Richard continues to modify and develop new billet products.

Brian the Joker steel fabricator wizard pondering the V-Rod.

Bandit and I ordered everything from Joker point cover to forward controls that have zero slop, positive lever movement, built in stop light switch and adjustable foot pegs so you don’t vibrate off the pegs. They make all the difference in the world as Bandit attested to on his ride to Sturgis on the Blue Flame. We will doll up the Rev Tech black and chrome 88-inch engine with Joker Rockers that are fully machined from solid billet. The Wedge design enables total serviceability while the motor is in the frame. Bottom section is completely o-ringed. Base is clearanced for larger diameter valve springs and feature a unique modular baffle system for excellent venting characteristics. We’re also using their hand controls because according to Bandit they’re perfect. Our order contained a myriad of the little item also, like small triangular rear turn signals, mirror, gas cap, oil breather, throttle housing, billet clamps and bullet head bolt covers.

Finally we jumped into my truck and headed back tothe ribbon of shimmering hot asphalt of the 210 Freeway. By the time we gotto the 605 Freeway, it was 5:00PM and the Freeways were all at a turgidstandstill, constipated with lumbering gas guzzling, smog spewing cars andtrucks. It was one of those many moments when we wished we had those tight FXRs splitting lanes toward the cool salt air of the coast.

Doctor John promises to have the frame finished for pick-up next week. We’ll report from his Anahiem, Ca location.

If you’re in the Southern California neighborhood, Joker Machine is sponsoring a show at the Grand Opening of the Route 66 Roadhouse and Tavern, June 22 at 1846 E. Huntington Drive, Duarte, California. Call (626) 357-4210 for more information on the shows and Pig Roast.

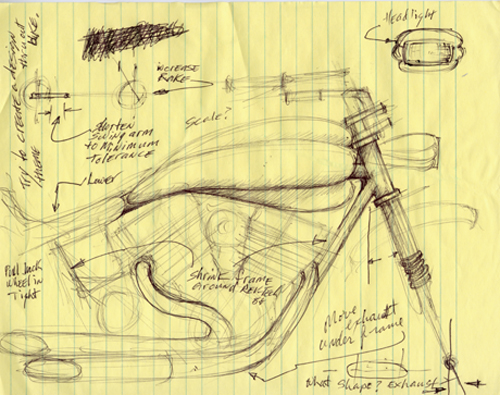

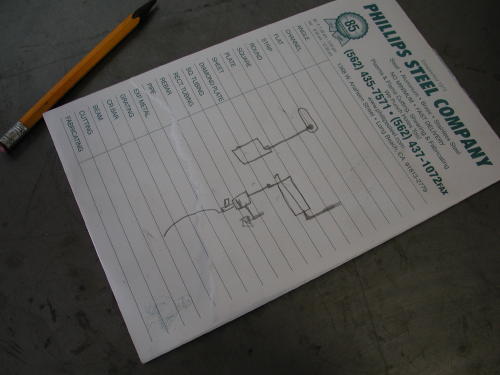

My first concept drawing which Bandit puked on and shit-canned.

Here’s the first of one of my bumbling concept sketches. We will be working with a racing Porsche sheetmetal fabricator on fenders, tanks and exhaust configurations. Wait until you see what Bandit and I come up with next.

Like the enigmatic fortunes you find inside thosefolded Chinese cookies, our visit with Dr. John–the”frame doctor,” was a mix of New Age mysticism andpractical guidance. The week before, Bandit and Ibrought the rolling Pro-Street frame to the gooddoctor. We gave the him our best ideas of what wethought the bike should become. Basically, we wantedthe bike to fit my body proportions, to shrink theframe around the engine and to still have elements ofa street chopper.

Bandit and I had been trying to create a bike that hada real “signature” identity, yet we weren’t sure whatthat would mean. We tried to convey our concepts withawkward babbling.

Stroking his long, gray beard with a knowing gravity,the doctor calmly listened to our ravings. Eventuallyhe gave us a broad grin through the tangle of beardand said, “Don’t worry, boys, I understand exactlywhat you need.”

We had left the bike with vague misgivings.”Do you think he really has a clue what we want?” Iasked Bandit.

“I dunno,” Bandit said, staring off into the acrid,smog-laden sky.”The guy’s kind of strange, but everyone I’ve talkedto says the guy’s a wizard,” Bandit musedmysteriously.

When we pulled up to Dr. John’s shop, there was ourcreation leaning up against the wall. Not averse tostreet-corner poetry, I intoned, “What a bitchin’fuckin’-lookin’ bike.”

“Man, that bike is really unique,” Bandit exclaimed ina more civilized tone.

As we oohed and ahhed about the bike, Dr. John camearound the corner, grinning. I jumped onto theseat-less bike and grinned. It fit perfectly, betterthan an O.J. leather glove.

“I really think you’ve got something good goingthere,” the doctor spoke with unconcealedappreciation. “I wasn’t sure it was going to workuntil I got into it. The bike began to speak to me. Ithink it’s got the right karma,” the doctor spoke withmysterious gravity.

All this mystery was not without reason. Dr. Johnstarted this trek to ultimate frame adjustment workingat Goodyear Tires. A fortuitous opportunity, sponsoredby Goodyear, for advanced training at L.A. Trade Techgave him the chance to try motorcycle repair.Recognizing that he was more interested in bikes thantires, he began a course in bike repair withinstructor Pat Owens.

Dr. John soon connected up with a bike shop calledMotorcycle Menders. Right away, he could tell that hehad a better-than-average sense of what was needed tofix most frames. Eventually, he opened his first shopin Covina in 1983. In 1990, he moved to his presentlocation in Anaheim.

Dr. John’s expertise is extended to both traditionalstreet choppers and to the more exotic road racebikes, where competitive tolerances and alignmentshave seconds off of lap times. The challenges to hisexpertise in frame adjustment include the extremes ofcreating a bike for a 6’9″ rider and a Harley with a25″ over stock front end. For his own use, he isbuilding a karma-tingling three-wheeler with a VWengine.

In his shop, amongst a tangle of tweaked Ninjacarcasses, “destruction derby” ATV frames, twistedchopper forks and even a mangled Vespa body, Dr. Johnholds court. Side-tracking his stories about gettinginto the frame adjustment business, he mixes conceptsof metal stresses with ideas of mental stresses,Eastern philosophy, acupuncture points, shakras andauras, martial arts movements, elements of a good dietand muscle alignment of the spine.

The conversation stumbles easily into his personalexperiences. After an injury of his own, he explored avariety of methods of pain control, eventually meetingan American Indian psychic whose exotic beautyhypnotized him as much as her cosmic consciousness.Here, a glint comes to his eyes and a wry smile bringsone corner of his mouth up. “A rare beauty,” hemuses. “An aura just like Cleopatra of ancient Egypt.”

Bandit nodded in agreement repeatedly, like thoseDodger dolls that bobble in the back windows of cars,to the good doctor’s banter. Bandit slurped his greentea while listening to enchanting tales spun by theDoctor. While I shoveled in heaps of steaming andspicy-hot Kung Pao chicken, my eyes teared up and mynose started running.

“The magnetic flow is a flux of energy in the bodyof…” The steaming pots of green tea and plates ofexotic Chinese food sent wisps and tendrils dancing inthe air above our table like a chorus of swaying,sensual nymphets.

“The assorted colors of shakra balance…” Thisadventure had the aura of Zeke the Splooty about it.We were on a cosmic motorcycle Magical Mystery tour.

An hour or so later, Bandit and I were back on the 91Freeway with the bike strapped to the bed of hispickup, staring ahead kind of dumbly. “What a trip,Dr. John is,” I said.

“Yeah, but I think he did a great job on the frame,”Bandit said.

“Yeah, cosmic man,” my head was stuck in the ’60s.”What do we do now?” I asked.

“Let’s check out some trippy paint for the bike,”Bandit smiled. “Let’s drive down to Stanton and see ifWes at Venom can come up with something exotic enoughfor this mystery machine.”

“Go for it,” I laughed.

It’s days like these that make bike building seem likethe right thing to do. Bandit slapped in a tape of’60s funk and we were sailing down the road like acouple of latter-day Kerouac and Keseys.

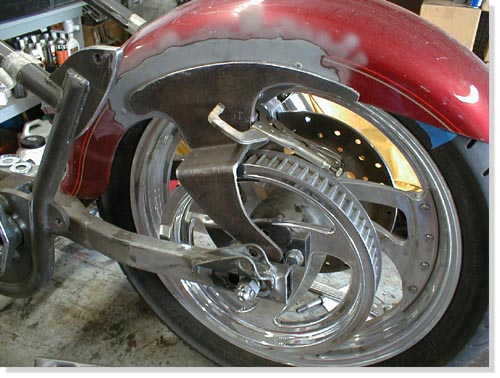

“Hand me a bigger hammer, goddamn it,” Bandit hollered across the garage. We were slamming together as much steel as we could to get this Frankenstein of a bike together in time to show it to the crowds at the Queen Mary Motorcycle Show this weekend.So far this week we’ve managed to cut 1.5 inches off the swing arm. This brings the wheel into the back end of the bike at the point of the pivot. We are designing the bike with brevity in mind. We are hoping that the finished impression will be a bike shrunken around the RevTech 88-inch motor and Rev Tech 6-speed. Oh, we’ll have devilish accents here and there, but the overall concept is lean and mean.

To that end, we are cutting off any unnecessary tabs and struts. Of course, everything changes as soon as a UPS box arrives. Joker Machine parts arrive every couple of days. The foot controls arrived. The new front Avon tire should be here Monday or Tuesday. It arrived, we had it mounted pronto and the fender was looking good. I hauled it to Urs who is a master body man and he widened it to fit perfectly. Having the right tools makes a big damn difference.

A new front tire was called for because the sexy front fender from Cyril Huze was too narrow, since he builds bikes for 19 and 21-inch from wheels and we’re running an 18 (our fault).

After banging the hell out of the fender to try to squeeze out a fraction of an inch clearance, we decided on a smaller sized tire. We ordered an 18/ 100-90. We hope this will allow us at least 3/8-inch all around.

The new Cyril designed stretched tank arrived with the fenders. We cut out part of the bottom of the tank at the back where the front of the seat is, since every goddamn thing we do is backwards. Every builder in the country stretches bikes, we shrink ’em, so the tank won’t fit without mods. This move helped bring the tank down closer to the engine and since the FXR is short, well you get the picture. The tank tabs are in place and welded.

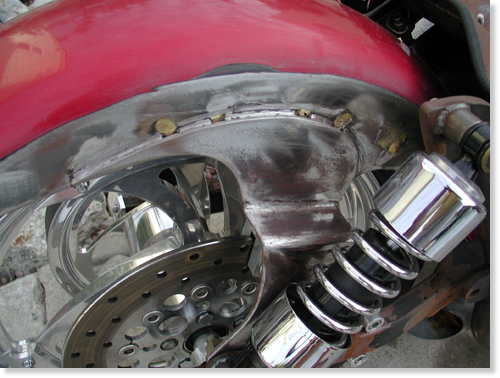

We decided to use an old rear fender off one of Bandit’s past bikes–a Fatboy. We turned it around backwards, the front end will be bolted to the center of the swing arm. Our next problem was how we were going to hold up the stern. After a lot of head scratching, cussing and phone calls we met with master fabricator James Famighetti who suggested that we create our own struts that will be bolted on the inside of the lower rear shock absorber bolt, then welded to the outside of the fender in such a way as to add to the over all look and strength of the fender and conceal the stock aspects. Mounting fenders to swingarms is treacherous. It will vibrate like a dog attacked by killer bees, so it better be strong and still able to remove for touchup.

No problem, you say? Ah, ha, not so easy kimosabe! We are pretty sure the strut will have enough clearance for the Rev-Tech brakes on the right side of the rear tire. When you come around to the left side, you’ve got the pully to contend with. So on this strut we added a 2″ dog leg to clear the pulley. I made up the patterns on cardboard and the Fam-Art brothers cut and bent the pieces. Then it was time to fit. We’re getting there.

The BDL pulley from CCI is smaller than the one we used for the mock up. So with our fingers crossed, when all these parts come together this week it will be amazing if they all fit. They did, well, perhaps not perfectly, but we’re getting close.They did, well, perhaps not perfectly, but we’re getting close. If not, “Bandit, get me a bigger hammer, goddamn it!”

Here’s the score. The fender needs tabs and it’s ready. The rear fender needs rivet removal and the massive tabs tack welded. The shock tabs have been cut since the Progressive Suspension shocks from Custom Chrome need to be set wider away from the fender tabs. Let’s see if we can make it to the show. We’re still waiting on Huze oil tank mounting tabs.

The saga of the Amazing Shrunken FXR continues. This project is notonethat is merely slapping together after-market products to build a facsimileof a customized Harley-Davidson.From the start, Bandit and I sought to create a unique ‘signature’ bike.Even though we have used a lot of after-market products, most have beenmodified to fit our design plan. The products we use, from the FXRPro-Street frame to the Rev-Tech engine to the Joker Machine qualitycomponents, to Cyril Huze, Avon and BDLare some of the finest products available.

Because some of the fundamental elements of design were modified, we havebeen constantly fabricating new brackets, tabs, mounts, and studs. Eachmodification created new issues relating to the fit and function of thedrivetrain. It seems as if we’ve bolted and unbolted the elements of this bike ahundred times.For example, the frame was modified by Dr. John to fit the Rev-Tech engineinto our overall design concept. The top motor mount was bent to fit thenewspacing. We used this motor mount point to position the Cyril Huze teardropgas tank. When we positioned the tank we related it to the handle barclearance at maximum turn position. Rubber mount brackets were welded inplace. The tank was cut at the underside back end to fit low on the frame.It looked hot. Next I cut the La Pere seat pan to hug the pointed rear ofthe gas tank and strengthened the seat back. There is a continuousdouble-‘swoop’from the handle bars to the back of the rear fender. The seat pan lookedhot.

Then we tried to put the engine in. It didn’t look fit. The engine wasmere fractions of an inch from fitting. Even if we could have hammered itinplace the subsequent tight tolerances would surely create problems as thebike rattled and roared down the road.

At this point, we cut the original tank brackets and repositioned themodified tank a little higher on the top frame tubing. The tank looked hot,the engine fit, but now the handle bar swing is a fraction of an inch tooclose to the tank. This means we will probably have to have custom handlebars.

It still looks good and we’re still optimistic. Even as wedroppedthe tank down on the new rubber mount brackets and began putting in the5/16″bolts, we found that the right rear bolt was too long to fit. So we got abolt with a thinner head and with my small fingers, I got the bolt in andstarted. We were still looking hot.

We decided to see if the belt fit since Bandit had cut andrewelded the swingarm 1.5 inches shorter for that Amazing Shrunkenlook. Bandit said no, the belt wouldn’t fit. It wasn’t suppose to. Isaid it looked close. As welooked at the bike we realized we’d had to remove the engine, drop thetransmission, which meant we’d have to support the swing arm. It alwaysseems harder than hell to make something easy. So with a couple of scissorsjacks, hunks of wood, and a crow bar, we were able to loosen the rubbermounton the left side of the pivot point of the swing arm. Then we gingerlyslipped the belt in, put the rubber mount back and bolted everything backtogether. Damn! It fit perfect and we were looking hot.

Wait a minute. The right side of the belt was almost touching the edgeofthe back fender. Quick surgery with a saws-all cut a chunk out of thefender. Fender fits, belt don’t rub, bike still looks hot.

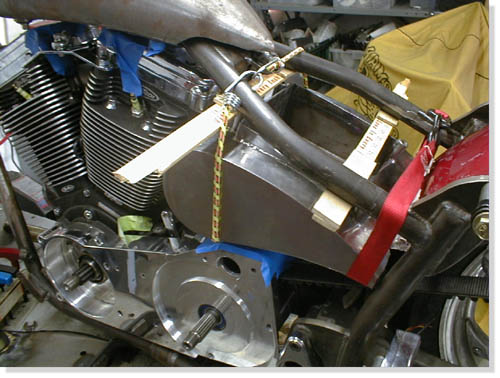

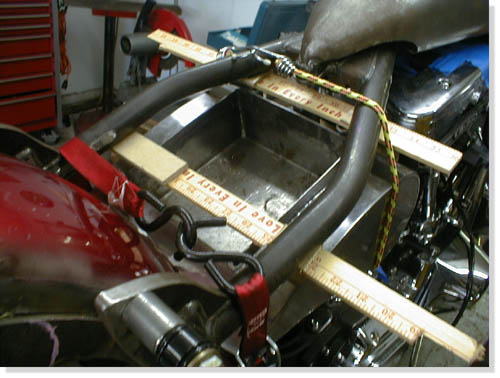

As we cram more operational parts together, the room to move gets lessandless. Next we positioned the oil bag, which also brought up the issue ofthebattery accessibility. With bungee cords, a busted yard stick and some woodshims, we finally got the bag in what seemed a reasonable position. Fourrubber mounted brackets were fabricated then welded into place. It lookedHot. Everything was bolted in place. And everything looked Hot.

Ah, but not so fast kimosabe. We shaved the fins off the back ofthe oil bag for more clearance. With the two rubbermounts in place atthe rear of the oil bag under the seat pan we had enough clearancefor the battery, in the front for the engine and exhaust, under itfor the starter motor, but no clearance for the ever moving rearfender. It needed at least 1.5 inches of shock play since it’sattached to the swingarm. We had to peel the bag out of the frame andtake it to the Famighetti’s metal fab shop, Fam-Art, for theirexpertise. They came up with a plan to scoop out the back of the bagto the battery box without shortening the overall look of the bag.Then the fender will have the clearance to move with the swingarm andstill look hot.

Next, we neet to investigate whether the Joker controls canbe mounted mid frame. At the same time we will begin fabrication ofthe Amazing exhaust system. It’s gotta be lookin’ hot one way oranother.

Bandit and I were checking out the Amazing Shrunken FXR. “Thedamned thing,” referring to the shrunken FXR project we had beenhammering at, off and on, for almost two years, “has attitude,” hegrowled, “a bad-assed attitude.”

“Yeah, but will it have sound attitude?” I mused. “I want it toget attention. I want it to be felt in their chests before they seeit. I want them to hide their children from the evil they fear.”

The Amazing Shrunken FXR has developed into a mythic ethos. Froma cardboard box full of rejected, beat-up, and cast off parts, thebike has become a sculptured icon, a physical dream, and perhaps awrong turn down a bad dirt road, three miles back.The project began back in the spring of 2001. After a lot of fitsand starts, the Buell Project, the Sturgis Run, the Deer Gut stewadventure, Bandit’s painful recovery, the Red Ball prep, variousevents including a trip around the world and soiree’s, we slappedparts on, hammered steel into shape, welded this and that, cussed andfarted and got to where we are with the help of a RevTech driveline,Custom Chrome, BDL belt, Joker controls, Cyril Huze sheet metal andCompu-Fire electrics. The bike is raw boned, trimmed down, and meanlooking. That’s where it stands, inert and waiting for inspiration,up on the rack at the Bikernet garage.

Bandit regarded the raw metal frame with squinty-eyed intensity.”What you thinkin’,” I asked, keeping my own gaze focused on thepotential of the bike. At my question he stretched out his gangly,egret-like frame to its full 6’5″. “It’ll be a loud mother fuckereither way you play it,” he intoned in his gravitas basso-profundodeep voice. “We’ve shortened the frame and rear wheel base so muchthat it’s barely a cunt-hair from the exhaust port to the rear wheel.”

We cut a piece of an Samson Evolution system with a Mikita touse the exhaust port, then started welding other pieces in place. Wecut it back to make a tight turn and create space away from the oiltank.

“Fuck it,” I responded in my best Pancho Sanchezimprovisation, “let’s just start from the port and see what happens.”

We rummaged through a pile of Samson scrap exhaust pipes that wehad scavenged from a dumpster behind the Sampson factory. Flingingout fish tail tips, shot gun systems and swoopy cruiser exhausts,most of them dented and damaged so they couldn’t be re-used. Mr.Samson gave us only the best to modify. We eventually came up withenough pieces to fabricate a Frankenstein exhaust system.

As I grabbed for a section 1 3/4-inch chrome pipe, Imistakenly grabbed a goodly chunk of fur. Bandit’s midget, crazeddemon of a feral cat yeowled in protest and sank his needle-liketeeth into the back of my hand.

“God damn that crazy bastard,” I screamed, “he’s as crazyas a peach orchard boar.” I’m sure Bandit has a mescaline salt-lickfor that freaked out feline.After I extricated my hand from the jaws of Bandit’s feline Cujo, Ireturned to the exhaust system at hand.

Our intent was to minimize the exhaust system as much as possible.We ran the pipe straight down from the front exhaust port, thenturned it to hug the bottom of the engine case. We had originallyhoped to put a flattened pipe under the frame, but reasonable roadclearance dictated a different path. So we tucked it in and aroundthe engine case, then inside the frame, coming out just at the edgeof the back wheel.

“Our first mistake,” Bandit spouted, “we needed a smallerdiameter chunk of exhaust to form guides when welding chunks ofexhaust together. If we had slipped it in one piece even a quarter ofan inch. it would have held each chunk in alignment. That’s onetheory to building pipes. The key to fabing your own pipes is havingenough scrap to slice and dice, then cutting and working each pieceuntil it’s as close to a perfect fit as possible. Finally the tackingprocess is critical. That’s were the guides didn’t come in. If we hadguides we wouldn’t have offset pipes tacked into place. That problememerged severely a week later during the grinding process.”

“It took two days of playing, cutting, fitting and welding toform a completely custom exhaust system in place,” Bandit added.”Make sure you wet towels and form a fire barrior around your tackingarea to protect the rest of the bike. I used a small 0-sized torchtip and common hanger to tack the segments of pipes together. I’m notconfident enough with our new MIG welder with thin sheet metal, so Istuck with the torch.”

” It wasn’t perfect, but it was ours,” Bandit added, “acompletely unique system that would be tucked under the transmissionand attached to the driveline solidly under the tranny backing place.Then we faced the muffler aspect. The pipes were too short to be openor we would have been arrested within a block of the headquarters.”

Needing some kind of ‘standardized’ muffler elements, we went toour local San Pedro Kragen Auto Parts store. With the clamp-on piecein hand, we found parts and pieces enough to create a 7″ mufflercase. “Most of the elements were too heavy and glass packed,” Banditspouted, “We couldn’t weld on a glass pack.”

Back at the garage, with torch in hand, Bandit cut out a sectionof baffles from some scrap Sampson muffler. Spot welding the bafflesinto our jury-rigged muffler, we produced something that may, likeJapanese Fart Wax, diminish the painful ‘Brap-rap-rap’ flutter ofunrestrained exhaust back pressure. A right-angle turn-out willdirect the dragon’s breath exhaust from the screaming 88cc Rev Tech,high-performance engine to an unsuspecting public standingslack-jawed and terrified at the curbed edge of civilization, theirhair-dos blasted straight by the sizzling after-burner of the AmazingShrunken FXR.

“He gets sorta twisted,” Bandit muttered shaking his head.”Actually with the baffle in hand we went to San Pedro Muffler Shopand looked at the myriad of tips and tubing alterations we couldmake. We found a tip and had a chunk of 1 7/8 tubing spread to matchthe tip. That formed the other end of the muffler. We just had toweld the three elements together.”

I welded the baffle in place, positioned as it was in theSamson System. I discovered that the two elements didn’t want to weldtogether. I have a feeling the tip was made of an inferior metal.

With the die grinder we cut notches for the muffler clamp.

“After welding and fitting I stood back and was proud of ouruniquely tight system that would allow Giggie, from Compu-Fire, tomachine mid-controls for a final touch,” Bandit interupted. Theexhaust played perfectly into the Shrunken aspects of the project. Iremoved the tacked system and began hours of gas welding to make itwhole. That’s when all hell broke loose. While working on anotheraspect of the bike with my back turned to my partner, he began togrind the welds. The college art history professor sought perfectionwith each weld and ground right through the thin walls of the18-guage exhaust pipes. It was amazing. I was sure the system wasruined.”

This shows the amount of area ground down so far we were forcedto fill it or destroy the system and start over.

“Some builders tack systems together then take them tomuffler shops for professional construction. I thought that was mynext move. Unfortunately a regular muffler shop doesn’t have themandrels to make the tight bends we had proposed. I was devastated,but the man told me that he could fill the welds with his MIG welder.

More welds to fill the mad grinder’s cutting work.

“Unfortunately each weld was now a 1/2 inch tall and wide zit atalmost each junction of the pipe. Nuttboy began the grinding processagain. More holes were found and I filled them with gas welding usinghanger rods. I joke now that if the bike runs like shit we blame iton the exhaust system. If it runs well, it’s the same roll of thedice. We’ll see.”

“Making your own exhaust system can be a blast, just don’tget heavey handed with the grinders. Pipe is thin and a little weldthat shows won’t matter much since we didn’t plan on chrome, butblack Jet Hot coating. I’ve sworn off chrome exhaust systems on mybikes for the future.”

That big bastard just won’t shut up. The next episode in thismechanical adventure will feature Giggy’s attempt a electrifying thesteel monster. Next weekend, barring any new bike projects, Giggy’sinopportune finger damage at the power tools, splattered deer guts,San Pedro political insurrection, Sin Wu’s beguiling charms, a caseof beer, or any other form of diversion or chaos, we will be closerto cranking this monster over.

Photos by Bandit and Sin Wu

It’s New Years Eve 2002 and catch up time on the ShrunkenFXR, as if I’ll melt if I don’t cross the line by midnight. And I’mgoing to lower the boom on you. It wasn’t intentional that Giggie,from Compu-Fire, came to the Bikernet Headquarters to help install aCompu-Fire charging, starter and ignition system. He added showing usthe benefits of installing S&S solids in the 88-inch Rev Tech engine.That would seemingly be enough, but since the starter involved theBDL inner primary, Giggie was snagged into helping with the beltdrive installation. That’s not all. As you will see in some of theshots we have Joker Machine forward controls installed, but we’vealways considered mid-controls. Unfortunately for the mastermachinist, we asked for Giggie’s impression and knowledgeablenotions. He dove right in and you’ll see the outcome here. There’seven more, but let’s get started.

I’ve been running Compu-Fire Electronics for several yearsand will continue to do so. The systems are flawless and a breeze toinstall. I’ve learned to trust their components and enjoy asingle-fire ignition. My discussions with Giggie ran into startingproblems I had encountered before. He pointed out to me that newhydralic systems bleed down as engines cool which closes valves whenyou want that puppy to fire to life once more. That’s where the S&Sportion of this tech began.

Here’s the deal. If the valves are closed while the starter motoris desperately trying to turn over the engine, especially aperformance unit, it’s a bitch. The compression is over the top, andthe electric motor is fighting an up-hill battle. The battery isbeing stressed. This situation is caused when the bike sits and thehydraulic lifters bleed down. Once it fires to life that situation isrelieved.

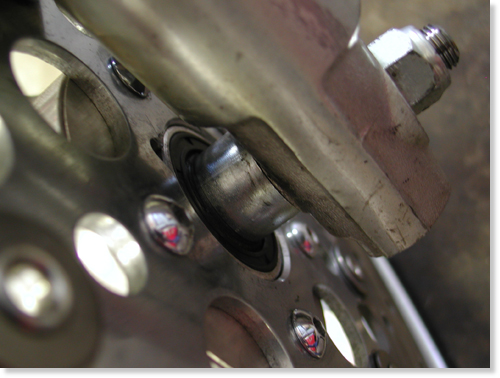

Giggie has been testing and improving starter systems for thelast three years with Compu-Fire. They are developing the mostelectrically efficient systems on the market, but discovered thishitch in the driveline system with the jammed valve train which putsundo pressure on an otherwise fine starter motor and battery. We madea date to install the new Compu-Fire Starter, but in addition, fourlittle rings from S&S would slip into the Rev Tech hydraulics. Sincethis Custom Chrome engine had non-adjustable pushrods we had to ordera set of Rev Tech aluminum adjustable pushrods. We removed the rockercover and arm assemblies to free the pushrods.

The lifter blocks had to be removed to retrieve the hydraulicslifters.

The following shots show the S&S solid ring installationprocess, I hope.

Giggie used snap ring pliers to remove and install the snapring to free the hydraulic piston.

With the lifter blocks removed, the lifter slipped outeasily, and with a snap ring plier tool Giggie removed the ring andthe spring and the piston came free. The S&S ring was slipped overthe hydraulic plunger spring and the rest is history. With the clipring back in place the hydraulics were ready to rock with the new RevTech Pushrods.

Giggie demonstrated how he adjusts pushrods by finding the intaketop dead center, TDC, position for the front cylinder first. When theintake valve is closing or the pushrod heading down, stick a straw orpencil in the spark plug hole and watch it travel north until it’s atthe top, TDC. check the timing hole for confirmation. Sure enough averticle slot showed up in the hole confirming our position. The camwas also in the perfect position to adjust both the intake andexhaust pushrods for the front cylinder, since both valves are closedfor compression. There is also an exhaust TDC.

The pushrods are adjusted just like old school, solids untilthere’s no up and down slack. You’ll notice that the rings don’t makethe hydralics completely solid but give them .020 slack. Once youhave each pushrod adjusted back off one complete turn. That will giveyou .020 cushion and once the bike runs for the first time you won’thave any tapping like the old scoots had. That’s an easy fix for amajor performance issue. I hate wasting starters or batteries.

Since we didn’t have the adjustable pushrods on hand we tookthe rocker boxes apart and Giggie pointed out another big inch motorfix. Performance engines that are pushed to redline can build upexcessive oil in the rocker box breathers. That oil will end up inthe air cleaner if it doesn’t have time to filter back through theheads into the oil return line. Creative Cycle Products, distributedby Custom Chrome, designed a fix for this problem. They call this theNose Bleed Cure which was designed to work on all late 1993 and upEvolutions with Nose Breather (engine vents in the heads) system.Installed, the kit eliminates the collection of oil at the bottom ofthe air cleaner assembly. It allows the engine to breath naturallywithout the mess in the air cleaner. The vent extensions, installedin the rocker boxes, allow more time for the oil to filter throughthe head.

The vent extension is a breeze to install, especially if therocker boxes are removed. The center rocker arm spacer has two areasin the corners for breathers. The inside cavity has a rubbermushroom, Umbrella Valve, poised to limit some air and oil into thearea. That’s the corner we’re concerned with. The extensions wereeasy to install in some respects in the Rev Tech Rocker Boxes andcreated another challenge in other respects. Let’s follow CreativeCycle’s instructions: If we had a battery we would have disconnectedit, first. Since our tank was easy to remove we 86’d it to make roomfor the operation. You could get away with just jacking up the tank.

Remove the front rocker box top plate following the servicemanual. Unbolt the sucker. Then remove the center spacer. Remove thegasket. If the engine is new you don’t need to replace it. Theinstructions also call for replacing the Umbrella valve, but youdon’t need to do that unless it is old and worn or you bury it inaluminum shavings. Umbrella valves generally last a long time, butheat sometimes damages them and they crack. If you are going toinstall the cure in a worn performance engine, replace the UmbrellaValves.

Drill the small drain hole with the supplied 1/8 bit. Using the13/32 drill, bore out the large drain hole. The Rev Tech rocker boxspacer already had a sizeable hole and didn’t need drilling. The ventextension slipped right in. On the opposite side of the spacer thehole was broad and open which didn’t secure the new vent extension atall, which is generally a mild press fit. We cleaned the spacerthoroughly and cemented the extension in place with sillicon on theunderside and let it set up before we re-installed the rocker with afresh gasket (generally the use of silicon on the inside of anyengine is forbidden. But since it’s Nuttboy’s bike, who cares). Makesure the ring is completely clean of any debri or burrs. In mostcases, according to the instructions, the vent extention is a pressfit into the new hole. Tape it gently into place, clean the rockerring thoroughly and re-install that bastard.

Now perform the same function with the rear head. Accordingto the diagram with the kit, the two breather sections you’re lookingfor are the inboard units closest to the carb. Makes sense. Theoutboard breather cavities are not used. If you are running a monsterengine and want to extend the extension, there are small ringsincluded in the kit to enhance the existing extension although youmay need to clearance the top rocker box cover.

One more time I’ll mention silicone. It’s not to be used in anengine since one little piece could severely block an oil passage anddestroy the engine. The other reason I mentioned it again was broughtto bear by Frank Kaisler and a neatly placed .38 against my righttemple. He whispered angrily in my ear that silicon will not cementitself to chrome. He suggested JB Weld after the chrome was groundaway for a clean sticky porous surface.

That’s two out of say five techs we need to cover. How thehell are we doing? If you have any questions about this modification,here’s the number for Creative (800) 368- 6217.

This entire tech process was handled in two differentsessions. During the first we discussed the mid controls notion withGiggie and he altered our course. We were headed in the direction ofstock FXR mid control mounts, that bolt or are welded to the frame.That notion would force us to created large sweeping mounts to clearthe BDL belt drive. Giggie had another notion. Run a shaft throughbushings built into the belt drive inner and outter covers, tolinkage much like stock through primaries, except we would mount thefoot peg on the end of the shaft for the cleanest possible approach.

On the right side of the bike we had to make a plate that wrappedaround the tranny cover that would carry a similar shaft that wouldact as the axle for the brake lever. He suggested that we hide themaster cylinder under the tranny close to the rear wheel for a tighthose run to the rear brake caliper. The pipes will wrap around theshaft for the right peg and brake lever. Seemed like a good idea,except for one thought. This is a rubber mount motorcycle and boltingthe pegs to the driveline was asking for foot vibration. We discussedthe concept with several riders and the reactions were varied from”we’re nuts”, to “What the hell”, to the notion that we could run oneset of billet pegs for around town and a vibro-padded set for theroad. We decided to run with Giggie’s concept and try the simplesuckers out.

When we met with Giggie again he demonstrated the outcome.He machined the shaft for the BDL unit and an aluminum guide tubewith brass bushings pressed into the covers. The support unit wasstrong enough to stand on. Next, we needed linkage and a shifter peg,then foot pegs. In this case the foot peg will rotate with theshifter, another odd approach.

Note the high-dollar precision sketch of right rear brakelinkage mechanism. I don’t get it, do you?

Moving right along we installed the Compu-Fire chargingsystem. This is a breeze, but first you must hit the Harley Shop oryour Custom Chrome Catalog for a set of Stator Torx screws. If you’renot sure which charging system you have here’s a clue: The 32-ampalternator kit is identified by the stator plug protuding from theleft crank case outer surface. The 22-amp stator plug is recessedinto the crank case surface. This particular system is designed tofit all Big Twin models 1981 and later. The rotor may be used withstators rated at 22 amp and 32 amps.

We used the contact cleaner for clearing the stator area ofgrease or debris. The WD-40 was used to let the plug slip into placegently.

We cleaned the area in the left side of the Rev Tech casesthoroughly with contact cleaner. Then we slipped the stator over themain shaft, but not into position. Giggie sprayed the alternator plugwith WD-40 and began to wedge it into the inner slot in the case.First you need to back out the Allen set screw in the case to allowthe plug to slide through. Once the plug is in position (protruding1/4 inch), tighten the Allen set screw with Permatex blue Loctite. Becareful not to over-tighten the screw which could short out thealternator and ruin your day. With the plug in place make sure thewires are safely routed then install and tighten down the stator withthe self Loctite’d Torx screws. Done deal.

Then Giggie slipped the smaller of the two massive washersover the shaft (except when 32 amp Harley-Davidson alternator kit isalready installed). If the Compu-Fire rotor is being installed on a1981-1988 model with the Harley-Davidson 32-amp alternator kitalready installed, the spacers and shim washers should already beproperly positioned on the sprocket shaft. Discard the washerssupplied in the kit and reuse the washers and shims in the samelocation from where they were removed. Compu-Fire charging systemsare perfect replacements for toasted charging systems.

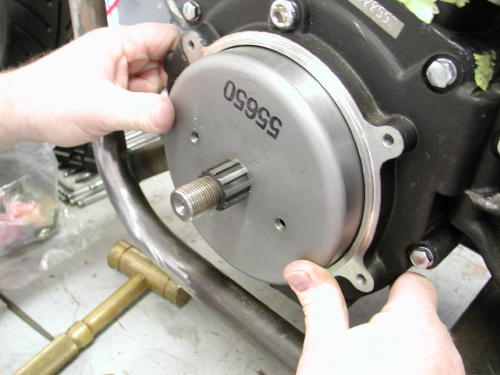

Then he took the BDL engine shaft insert and slipped it onto thesplined sprocket shaft to check the fit. Some sprocket shafts fromJIMS and S&S were slightly different sizes. The splines were machinedto be .001-inch larger across the face. Since the BDL insert fitsnugly, but fit he attempted the same manuever with the Compu-Firerotor. When we installed a rotor on the Redball chopper, we had tofile each tooth to make it fit. That wasn’t the case this time aroundsince Giggie ordered the Compu-Fire rotor with the larger slots orsplines. Note the number on the rotor. The 650 unit is alreadyprepared for the larger shaft, whereas the 600 unit was built forearlier alternator motors. If you need to remove an old rotor you mayneed a JIMS machine tool or a Harley-Davidson puller part no.95960-52B. Be careful that the magnets in the rotor do not pick upsmall metal parts or hardware from the work area before you installit.

Also note the warning label on the rotor. It says not tosmack the rotor with anything. If you do so severely you could knocka magnet loose, or you could change the polarities on the magnets.Don’t hit it with anything harder that the palms of your hand. Thisone was snug, but slid right into place. Now comes the large flatwasher. This puppy is there for strength. With everyday use the faceof the rotor will flex and can crack. This washer adds strength tothe face and prevents cracking. Don’t forget it.

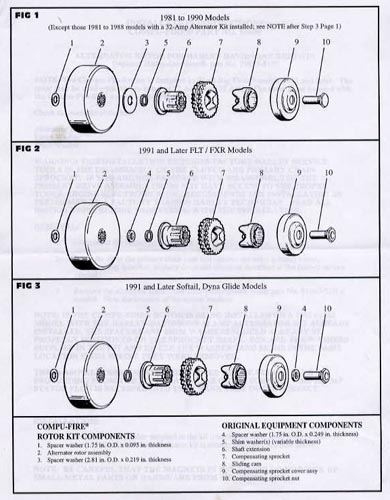

Here’s some notes regarding different models. Thisinformation is supplied with all Compu-Fire charging systems:

To install rotor on 1981 to 1990 Big Twin) except those witha 32 Amp alternator kit installed) place the large washer suppliedand original shim washers over the sprocket shaft (in that order).See figure 1.

To install rotor on 1991 and later FLT/FXR models, discardthe large washer supplied in the kit. Place the original washer andshims over the sprocket shaft (in that order). See figure 2.

To install rotor on 1991 and later Softail and Dyna Glidemodels, discard the large washer supplied in the kit. Place theoriginal shim washer over the sprocket shaft. The original thickspacer washer will be used under the compensating sprocket nut onfinal assembly. See figure 3.

If your are installing this Compu-Fire kit on a stock bike,next you would re-install the primary drive assembly per factoryservice manual and use loctite (red) on the threads of compensatingsprocket nut. The compensating nut must be torqued to the correctspecifications:

1981-1990 models 80-100 foot pounds

1991-Later models 150-165- foot pounds

(for aftermarket shafts use manufacturers specifications.)

Don’t forget to put oil back in the primary.

That left the regulator. In the past you would be forced toinsure a proper ground by cleaning some of the regulator case surfaceof paint, the bracket surface and paint off the frame. That’s nolonger the needed. These regulators come with a separate groundstrap, which Giggie recommends that you attach to the engine case onthe right side under the cam cover to hide it. “Make sure the wire iscrimped to a lug, not soldered,” Giggie pointed out, “and that thecase is clean of wrinkle paint before it’s bolted in place.”

One other wire is afforded with the regulator, the hot wire,which generally runs to a circuit breaker, the battery hot terminalor the ignition switch hot side. There’s a specific reason for notsoldering lugs or connectors, but crimping them. According to Giggiesoldering induces heat to the wires and a completely solid lead bondthat creeps under the wire insulation. The combination creates abrittle point in the wires that can deteriorate and crack withvibration. Wire connectors do not come with the regulator kit. Youneed to find the appropriate size for your application.

While Giggie was tinkering in the Compu-Fire machine shop,building prototype components for their line of products and slippingin a Shrunken FXR parts, in his free time, we installed 3 ohm Dynacoils required for the single-fire Compu-Fire ignition system. Theyare available from Custom Chrome in 6 and 12-volt models, with singleor dual towers and in 1.5, 3.0 and 5.0 ohm configurations. We chose astrong billet German made bracket, from Custom Chrome, to hold thecoils between the heads. This is one of the cleanest ways to run theelectrics with all the elements close together. The coil bracket fromCustom Chrome was also capable of holding the ignition switch and ahorn button or toggle high/low beam switch. That would be the extentof the wiring for this bike and it would all be tucked under the gastank and between the heads cleanly.

We have also ordered a CCI ignition switch discovered from thewater-craft industry by Bob McKay. It works like automotive ignitionswitch with a key and acts as the starter button eliminating the needfor a starter relay.

What should we handle next, the ignition system or the BDLBelt Drive? Your call? The BDL Belt, okay, here goes. Actually theseunits are increasingly easy to install. Late model bikes with rubbermounted drive lines are in solid alignment which makes these unitslip right into place. Just in case you are working with a pre-unitmodel I will list some alignment recommendations from Frank Kaisler.

This particular BDL installation came with their brand new SuperStreet Clutch which consists of nine fibers and 11 steels. Installtwo steels first then alternate fiber and steel ending with a steelbehind the pressure plate. Install anywhere from four to nine springsand bolts depending on how much spring pressure is needed for yourapplication.

“With this much clutch surface, not much spring pressure will beneeded for proper engagement,” Said Bob from BDL. For additionalspring pressure for monster engine and abusive clutch throwers theyincluded washers to enhance the clutch pressure.

Basically Giggie installed the backing plate first using thefasteners supplied by BDL. Installation on 1986-89 models require theuse of a 1990-up starter and modification to the starter mountinghole on transmission will be necessary. You must open the mountinghole to 2-1/8 inches.

Remove the stock starter pinion gear and complete starter gearassembly from starter. Bolt starter into back side of motor plate.

Install the front and rear pulleys and check for proper fit. Atthis time you should determine if the front pulley will need shimmingor not depending on how the pulleys align with each other. Removepulleys and add shims if necessary.

Re-install belt drive placing front pulley, rear pulley and belton at the same time or you’ll discover it’s tough going. Install andtighten to H-D specifications, mainshaft hub nut. BDL supplied aspecial hub nut with seal for all spline shaft models 1990 and later.Engine shaft splines should not protrude from the pulley. Be sure tored Permatex Loctite front engine nut and torque to H-Dspecifications (an electric impact driver is used but notrecommended). JIMS and CCI carry a tool that will lock the pulleys soyou can use a torque wrench. For 1986-89 taper shaft models you mustuse the stock hub nut and seal kit (included).

For spline mainshaft models, 1990-up, apply red Permatex Loctiteonto the back of the BDL hub 1/4-inch inside of the spline and letthe Loctite flow onto the mainshaft when sliding the rear basketassembly on. This procedure is necessary so that the hub andmainshaft will fit together properly and will not let the mainshaftspin inside of the BDL hub. This procedure is not necessary on tapershaft models 1986-89.

(The belt drive was designed with the use of stock H-D frames.The shaft to shaft dimensions on a stock Softail are 12.825 and on anFXR is is 11.325. The number of teeth on the pulleys and the numberof teeth on the belt were engineered to exact fit using the abovedimensions. If aftermarket frames, engines or transmissions are usedthen these dimensions may very slightly. You may need to address thisproblem so that the kit will fit properly. We will not be able tohelp you with this problem, this is an issue to be addressed by themanufacturer of the aftermarket parts that you may be using.)

Rotate the motor (take the plugs out) using a socket wrench, thebelt should track straight and away from the motor plate, but not sothat it may come in contact with the outside pulley flanges. Be surethat the belt drive is not making contact with the motor plate.

Grease the starter shaft and install the BDL starter pinion gearonto the starter shaft, apply red Permatex Loctite to the starterbolt and tighten to H-D specifications (they supply two starter boltswith the kit, one is a 1/4-20 by 2.5 inches for 1990-93 starters, theother is a 10-32 by 2.5 inch for 1994 and up starters. Be sure not totighten starter bolts too tight as this may interfere with properengagement to the clutch ring gear.)

Install the clutch pack, refer to schematic spline steel first,1/2 sided friction plate with fiber facing out, then alternate steeland two sided fiber plates ending with the other 1/2 sided frictionplate with the fiber facing in. This is for the regular clutch andnot the Super Street Clutch which was covered above. Install pressureplate, springs and shoulder blots.To install shoulder bolts apply redPermatex Loctite to a bolt and run in one turn, go onto the next boltuntil all the bolts are in place, then tighten them all the way downuntil they bottom out. There is no adjustment to the spring pressure,this is all pre-determined with the length of the shoulder bolt andexact dimensions of our pressure plate.

Install the four hexagon cover plate extensions into motor plateand mount side guard with the four button head allen blots.

Clutch screw adjustment should be 3/4 to 1 turn loose from lightlyseated. Note: When the clutch is hot the adjustment screw should notbe seated. Tighten rod nut when adjustment is complete. BDL suppliesa clutch adjusting rod and nut for all models 1990 and up, only.

If your bike is perfectly level, if you put a level on thisruler, it should be level.

SIDEBAR; ALIGNMENT CHECKS FOR RIGID MOUNT DRIVE LINESWith the engine in place and all the lower engine mounting boltsinstalled but loose, take a straight edge and place it on the innerprimary mounting surface of the engine. Look at the straight edge toinsure that the sprocket is parallel to the straight edge, if not trymoving the engine around until the straight edge and sprocket areparallel.