Climate Journalists Are In The Grip Of A Weird Religious Cult

The failure of Texas to implement flood warnings, not climate change, caused those 27 deaths

By Michael Shellenberger, courtesy of Public Substack (you can listen to Michael tell this story on Public Substack)

https://www.public.news/p/climate-journalists

Climate change caused the catastrophic floods that tore through Central Texas over the last few days, killing at least 27 people, including nine children, and turning calm rivers into violent torrents, according to the media. At Camp Mystic in Kerr County, the Guadalupe River surged from about three feet to nearly 29 feet in just 90 minutes, sweeping away cabins, vehicles, and people with little or no warning. Climate change caused a warmer atmosphere, which holds more moisture, and unleashed it in increasingly intense bursts. Volumes of precipitation were extreme. They had less than a 0.1% chance of occurring in any given year, according to the New York Times. Texas climatologists warned that the frequency and severity of such events have already increased and could intensify by another 10 percent by 2036. In East Texas, “the number of days per year with at least two inches of rain or snow has increased by 20 percent since 1900,” noted the Times.

But that tiny increase in precipitation doesn’t explain the floods or the deaths in Texas. Over the past century, global flood deaths declined by more than 80 percent. That happened not because nations reduced rainfall but because they have learned how to live with it. They built levees, dams, and drainage systems. They developed early warning systems and evacuated people before the water arrived. Kerr County in Texas failed to do any of these things. Despite its location in one of the most flood-prone regions in the United States, the county had no formal flood warning system in place. There were no sirens, no automated text alerts, no rapid evacuation protocol. The river rose, and families had no idea it was coming.

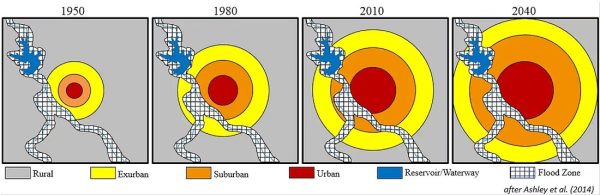

The IPCC has made clear that while global warming contributes to more intense rainfall, the impacts of these events are shaped by how societies respond. Bangladesh offers one of the clearest examples. Once synonymous with catastrophic floods, the country has invested heavily in preparation. During Cyclone Sitrang in 2022, the government evacuated nearly one million people using mobile alerts, loudspeakers, and a network of raised concrete shelters. Despite severe flooding, the death toll remained below 30. Bangladesh did not escape the storm. It planned for it. The extent to which more areas are being flooded is because, since the 1980s, share of the human population in flood-prone areas increased almost twice as fast as in less flood-prone areas, something known as the “bulls-eye effect.”

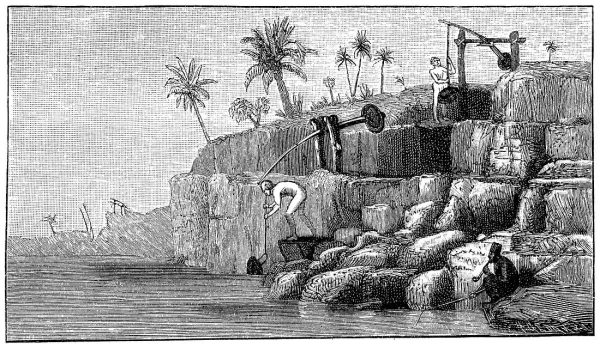

Schaduff, also known as Schaduf, is an irrigation device that was used very early in the gardens of ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia. (Photo by: Bildagentur-online/Universal Images Group via Getty Images)

Flood control is hardly a new thing. It is one of the oldest and most essential human technologies. Around 3000 BC, the Mesopotamians constructed canals and levees to manage the unpredictable flooding of the Tigris and Euphrates. By 2600 BC, the Indus Valley civilization developed advanced drainage systems in cities like Mohenjo-daro, capable of redirecting floodwaters away from homes. In approximately 2200 BC, engineers in ancient China constructed dikes along the Yellow River to protect farmland from seasonal flooding. The Romans began constructing aqueducts in 312 BC, not only to deliver clean water but also to manage storm runoff and reduce urban flooding. In the 1300s, Dutch villagers constructed dikes and windmills to drain marshes and defend their lowlands against the sea, laying the foundations for the modern Netherlands.

An etching from a painting of Amsterdam featuring the Royal Palace of Amsterdam and the surrounding area of the city, other multistory brick and stonework buildings can be seen in the area of the palace and around the canal, boats can be seen on the water while people walk along a long wooden dock, Amsterdam, Netherlands, 1800. From the New York Public Library. (Photo by Smith Collection/Gado/Getty Images).

Humans have known how to prevent flood deaths for more than 5,000 years. But in Kerr County this summer, that knowledge went unused. This was not the inevitable cost of climate change. It was the preventable cost of ignoring everything human civilization already knows how to do. And the idea that climate change’s modest impact on precipitation alone determines disaster outcomes is not just mistaken, it is fatalistic. It suggests we are powerless to adapt, when in fact we have centuries of knowledge and the tools to prevent tragedy.

These same media outlets ignored centuries of successful water and land management, erased the dramatic decline in natural disaster deaths, and dismissed the progress made by societies that adapted to environmental challenges.

Legacy outlets like The New York Times and The Guardian have spent years promoting worst-case climate scenarios while downplaying adaptation, innovation, and resilience. They elevated speculative models and catastrophic projections, often without context or probability, and presented them as inevitable futures. In doing so, they helped create a new category of mental illness: climate anxiety disorder, now common among young people who genuinely believe the world is collapsing. One in five British children reported nightmares about climate change in 2020.

Why is that? Why are the New York Times and other media promoting the idea that the Texas floods and deaths were caused by climate change? What’s behind the hysteria?

To answer those questions, it’s important to keep in mind that floods are not the only extreme weather event that the New York Times and other media outlets wrongly attribute to climate change. Over the past decade, reporters have increasingly blamed global warming for heat waves, hurricanes, wildfires, and even cold snaps, often before any formal scientific attribution is possible. These stories frequently cite isolated studies or speculative expert quotes while ignoring the broader data. The media’s tendency to link every disaster to climate change not only distorts the public’s understanding of risk, but also shifts focus away from the practical steps that reduce harm: infrastructure, preparedness, and smart policy. By treating climate as the sole villain, journalists often overlook the more immediate cause of disaster, human failure to plan for known threats.

Part of the reason is that fear sells, and news organizations are desperate for money. In an era of collapsing ad revenue and declining trust, sensational stories about apocalyptic climate disasters generate clicks, shares, and urgency. Tying every flood, fire, or storm to global warming creates a moral narrative that keeps readers emotionally engaged and politically alarmed. But this panic-driven coverage often substitutes drama for accuracy, and outrage for nuance. It rewards worst-case speculation over sober analysis, and ignores the far less dramatic truth: that many climate-related risks are manageable, and that human adaptation has already saved millions of lives. By amplifying fear instead of focusing on solutions, the media not only distorts public understanding but also undermines the very resilience needed to face a changing world.

Scientists respond to incentives, and in climate research, those incentives often encourage exaggeration of findings. Researchers who describe their findings in the most alarming terms tend to attract more media coverage, citations, and funding. Universities and journals favor studies that emphasize catastrophe rather than moderation or uncertainty. Policymakers and journalists often amplify the most dramatic claims, overlooking the caveats. This dynamic creates a feedback loop. Scientists who issue dire warnings receive more attention and resources. The system does not require dishonesty, but it rewards those who lean into worst-case scenarios. That bias shapes public understanding and distorts what climate science actually shows.

Another part of the climate narrative is strictly ideological. Climate alarmism gives radical Malthusian activists and intellectuals who view Western civilization as inherently destructive a moral justification for demanding its dismantling. They frame fossil fuels not just as a technical problem but as a symbol of greed, colonialism, and inequality. Under this view, climate change becomes a vehicle for broader political goals, redistribution of wealth, centralization of power, and permanent subsidies for green industries aligned with their agenda. Instead of focusing on practical solutions like adaptation, infrastructure, and innovation, these ideologues promote a vision of collapse and forced transformation. The climate crisis, in their hands, becomes less about physics and more about power.

Part of the climate alarmism discourse functions as a form of secularized Christianity. It follows a familiar structure: humanity has sinned (by burning fossil fuels), the planet now suffers as punishment (through floods, fires, and storms), and salvation can only come through repentance and sacrifice (by giving up consumption, flying less, eating plants, and trusting in technocratic authorities). This moral framework replaces God with “the science,” sin with carbon emissions, and redemption with policy obedience. Like religious movements of the past, it promises both judgment and deliverance, but only for the righteous. It channels guilt, fear, and the desire for meaning into a narrative that demands personal purity and societal transformation. While genuine environmental concerns drive many activists, the emotional energy behind the movement often draws more from theology than from data.

But the apocalyptic climate discourse differs from Christianity in fundamental ways. Traditional Christianity offers forgiveness, hope, and the possibility of redemption through the gift of grace. Climate alarmism, by contrast, often offers no forgiveness, only permanent guilt and endless sacrifice. In Christianity, an individual can repent and be saved; in climate ideology, the individual remains complicit, regardless of how many carbon offsets they purchase or how strictly they follow the rules. Christianity locates ultimate authority in a transcendent God; climate ideology places it in expert institutions and bureaucratic consensus. Where Christianity separates sin from the sinner, allowing for mercy, climate alarmism tends to treat dissent as heresy and skeptics as morally corrupt. The result is a belief system that mimics the structure of religion but replaces its spiritual core with politics, fear, and control.

In many ways, the climate discourse resembles the spiritual tradition of Gnosticism more than Christianity, as my colleague Alex Gutentag has pointed out. Gnosticism emerged in the first and second centuries AD as a radical spiritual movement within the early Christian and Hellenistic world, teaching that the material universe was a corrupt prison created by a false god, often equated with the God of the Old Testament, known as the Demiurge. In contrast to orthodox Christianity, which viewed creation as good and sin as moral failure, Gnostics believed that human beings contained a divine spark trapped in flesh and that salvation came not through faith or obedience but through hidden knowledge (“gnosis”) of their true, spiritual origin. Drawing on Platonic dualism and Persian cosmology, Gnostic texts like the Gospel of Thomas, Gospel of Truth, and Gospel of Judas, discovered in 1945 at Nag Hammadi, portrayed Jesus not as a savior who died for humanity’s sins but as a revealer of esoteric truths meant to awaken souls from the deception of the material world. Christians declared it heretical, but Gnosticism’s tradition of rejecting worldly authority and urging the embrace of inner divinity continues to influence esoteric, modern spiritual, and political movements today.

Like the ancient Gnostics, climate alarmists often claim access to secret knowledge that sets them apart from the masses. Writers like David Wallace-Wells, a New York Times columnist, openly describe their understanding of climate change as a kind of revelation. It’s information so dire, so morally charged, that it separates the enlightened from the ignorant or corrupt. In his 2019 book, The Uninhabitable Earth, Wallace-Wells wrote that one of the most haunting aspects of learning about climate change is carrying knowledge that others don’t share, and that feels impossible to convey. This mirrors the Gnostic belief that salvation comes not through faith or works, but through possession of hidden truths. In the modern climate version, those truths are wrapped in technical jargon, worst-case scenarios, and apocalyptic timelines. Those who accept them are the elect. Those who question them are heretics. And like Gnosticism, this framework often rejects the material world not as something to steward and improve, but as something irreparably damaged, a fallen system from which only a purified elite can escape.

This Gnostic discourse flows from and reinforces a kind of narcissism and arrogance. Those who embrace it often see themselves as morally and intellectually superior, set apart from the ignorant masses who continue to drive, fly, eat meat, or doubt the most extreme projections. They view their anxiety not as a personal emotion but as evidence of their enlightenment, their capacity to feel what others are too blind or selfish to comprehend. This posture flatters the ego while demanding no practical accountability. It fosters the notion that knowing the “truth” about climate change confers virtue in itself, regardless of whether one’s actions are practical, realistic, or even coherent. Like ancient Gnostics who saw themselves as illuminated souls trapped in a corrupt world, today’s climate elect often speak as if they have transcended ordinary political and moral concerns. In doing so, they attempt to insulate themselves from criticism and dismiss disagreement not as reasoned dissent, but as dangerous ignorance or denial.

The irony is that their alarmism often showcases their ignorance, especially when it comes to the long, practical history of water management and flood control. While they warn that rising seas and heavier rains make catastrophe inevitable, they overlook the fact that humans have successfully confronted these challenges for millennia. As I noted, ancient civilizations in Mesopotamia, the Indus Valley, China, and Rome constructed canals, levees, dikes, and aqueducts to harness rivers and safeguard cities. In the modern era, countries such as the United States, the Netherlands, and Bangladesh have significantly reduced flood-related deaths through the implementation of early warning systems, basic infrastructure, and coordinated evacuation plans.

Rising secularism, overprotective parenting, indulgent education, and the decline of reading have weakened the public’s ability to think historically and critically. Social media amplifies this trend by rewarding emotion over reflection and fear over facts. Without religious frameworks, many people turn to climate activism for a sense of purpose and morality. Without schools that demand rigor or resilience, children learn to fear complexity and retreat into simplistic narratives. Without books and historical knowledge, students lose perspective on how societies have solved problems like floods and natural disasters before. Those cultural forces feed climate alarmism and make it harder to challenge. People absorb panic more easily than context. As long as these trends continue, the drivers of climate fear will grow stronger and more entrenched.

Happily, we are also seeing a massive backlash against climate alarmism, as the 2024 election of Donald Trump made clear. Voters rejected the moralizing and fear-driven narratives of the climate establishment and chose instead a candidate who openly challenged its premises. In office, Trump moved quickly to withdraw from the Paris Agreement, halt environmental regulations, and eliminate federal subsidies for wind, solar, and electric vehicles. His administration redirected support toward fossil fuels and nuclear energy, restoring an “America First” approach to energy policy. These moves reflect not just a political shift, but a deeper cultural pushback against climate fatalism and anti-civilization Malthusianism that have defined the environmental discourse since World War II. Trump’s victory signaled that millions of Americans are tired of being told that prosperity, growth, and modern life are a problem to be solved rather than a legacy to be defended.

The more the media amplifies climate alarmism, the more it undermines its influence and credibility. This outcome is not just political, it’s cultural and psychological. The media didn’t just report on this narrative; it created it, fed it, and enforced its boundaries. It turned skepticism into sin, and consensus into dogma. However, as this narrative becomes increasingly extreme and detached from reality, more people walk away. Readers turn to independent voices. Trust collapses. Subscriptions fall. The backlash grows. The same media institutions that sowed fear and moral panic now watch as their cultural power shrinks, and that may be the healthiest development of all. Today, just 31 percent of the American people say they trust the media.

As such, things have the potential to change for the better, both in discrediting the climate apocalypse narrative and in restoring a more grounded approach to energy and natural disasters. The exposure of exaggerated claims, the collapse of media trust, and the rise of populist backlash have already begun to shift the conversation. People are starting to reject the notion that every flood, fire, or storm is evidence of societal collapse. On energy, voters are rediscovering the importance of abundance, affordability, and sovereignty, and are showing renewed support for reliable sources like natural gas and nuclear energy. As the alarmist narrative breaks down under the weight of its own failed predictions and political overreach, a more constructive vision can emerge, one rooted in problem-solving, human dignity, and confidence in our ability to shape the future rather than fear it.